Easily implement your custom Gymnasium environments for real-time applications.

Real-Time Gym (rtgym) is typically needed when trying to use Reinforcement Learning algorithms in robotics or real-time video games.

Its purpose is to clock your Gymnasium environments in a way that is transparent to the user.

rtgym has two implementation:

"real-time-gym-v1"relies on joining a new thread at each time-step, it is not thread-safe."real-time-gym-ts-v1"relies on signaling via python Events, it is thread-safe.

Both implementations should perform similarly in most cases, but "real-time-gym-ts-v1" is not thoroughly tested yet.

- Installation

- Real-time Gym presentation

- Performance

- Tutorial: Implement custom tasks

- Contribute

- Sponsors

rtgym can be installed from PyPI:

pip install rtgymReal-Time Gym (rtgym) is a simple and efficient real-time threaded framework built on top of Gymnasium.

It is coded in python.

rtgym enables real-time implementations of Delayed Markov Decision Processes in real-world applications.

Its purpose is to elastically constrain the times at which actions are sent and observations are retrieved, in a way that is transparent to the user.

It provides a minimal abstract python interface that the user simply customizes for their own application.

Custom interfaces must inherit the RealTimeGymInterface class and implement all its abstract methods. Non-abstract methods can be overidden if desired.

Then, copy the rtgym default configuration dictionary in your code and replace the 'interface' entry with the class of your custom interface. You probably also want to modify other entries in this dictionary depending on your application.

Once the custom interface is implemented, rtgym uses it to instantiate a fully-fledged Gymnasium environment that automatically deals with time constraints.

This environment can be used by simply following the usual Gymnasium pattern, therefore compatible with many implemented Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms:

from rtgym.envs.real_time_env import DEFAULT_CONFIG_DICT

my_config = DEFAULT_CONFIG_DICT

my_config['interface'] = MyCustomInterface

# CAUTION: "real-time-gym-v1" is not thread-safe, use "real-time-gym-ts-v1" for thread-safety

env = gymnasium.make("real-time-gym-v1", my_config, disable_env_checker=True)

obs, info = env.reset()

while True: # when this loop is broken, the current time-step will timeout

act = model(obs) # inference takes a random amount of time

obs, rew, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(act) # transparently adapts to this durationYou may want to have a look at the timestamps updating method of rtgym, which is reponsible for elastically clocking time-steps.

This method defines the core mechanism of Real-Time Gym environments.

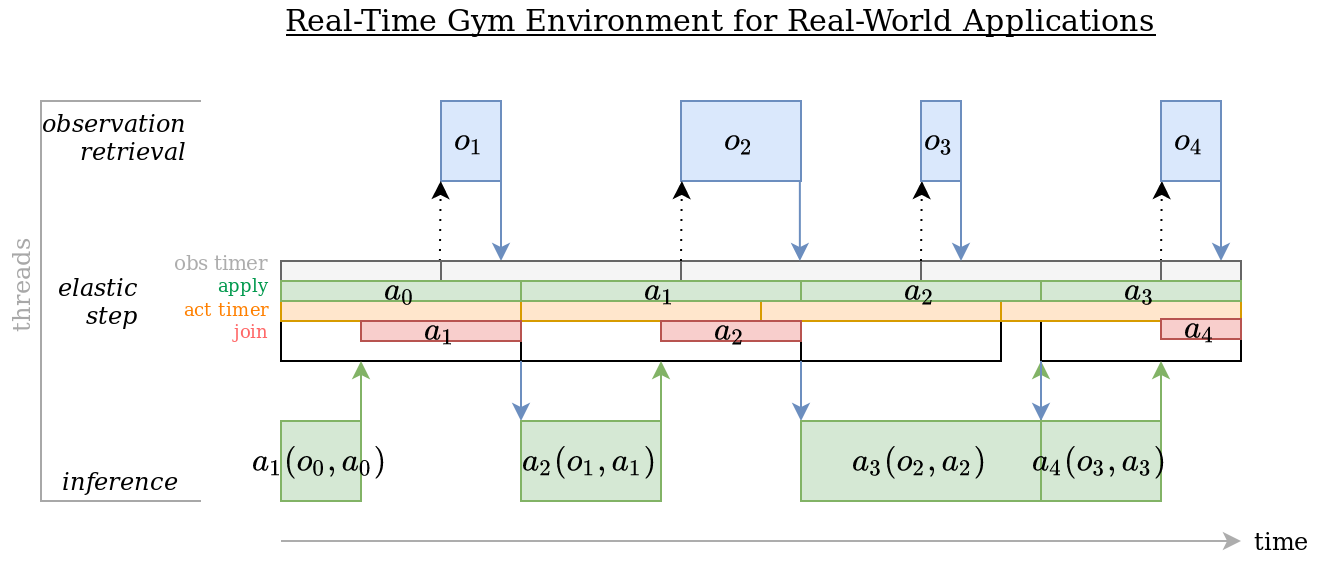

(Note: this diagram describes the "real-time-gym-v1", non thread-safe implementation.

The "real-time-gym-ts-v1" thread-safe implementation is similar, but uses a persistent background thread that is never joined.)

Time-steps are being elastically constrained to their nominal duration. When this elastic constraint cannot be satisfied, the previous time-step times out and the new time-step starts from the current timestamp. This happens either because the environment has been 'paused', or because the system is ill-designed:

- The inference duration of the model, i.e. the elapsed duration between two calls of the step() function, may be too long for the time-step duration that the user is trying to use.

- The procedure that retrieves observations may take too much time or may be called too late (the latter can be tweaked in the configuration dictionary). Remember that, if observation capture is too long, it must not be part of the

get_obs_rew_terminated_info()method of your interface. Instead, this method must simply retrieve the latest available observation from another process, and the action buffer must be long enough to handle the observation capture duration. This is described in the Appendix of Reinforcement Learning with Random Delays.

A call to reset() starts the elastic rtgym clock.

Once the clock is started, it can be stopped via a call to the wait() API to artificially "pause" the environment.

reset() captures an initial observation and sends the default action, since Real-Time MDPs require an action to be applied at all time.

The following figure illustrates how rtgym behaves around reset transitions when:

- the configuration dictionary has

"wait_on_done": True waitis customized to execute some arbitrary behavior- The default action is

a0

In this configuration, the "reset_act_buf" entry of the configuration dictionary must be left to True, and arbitrary actions can be executed in the wait and reset implementation of your RealTimeGymInterface.

When the "reset_act_buf" entry is set to False, "wait_on_done" should be False and reset should not execute any action, otherwise the initial action buffer would not be valid anymore.

Setting "reset_act_buf" to False is useful when you do not want to break the flow of real-time operations around reset transitions.

In such situations, a1 would be executed until the end of reset, slightly overflowing on the next time step (where a0 is applied), i.e., giving your RealTimeGymInterface a little less time to compute a4 and capture o4.

In case you want a2 to be executed instead of a0, you can replace the default action right before calling reset:

obs, info = env.reset() # here, the default action will be applied

while True:

act = model(obs)

obs, rew, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(act)

done = terminated or truncated

if done:

env.set_default_action(act)

obs, info = env.reset() # here, act will be applied(NB: you can achieve this behavior without resorting to set_default_action. Just set "last_act_on_reset": True in your configuration dictionary.)

In this code snippet, the action buffer contained in obs is the same after step and after the second reset.

Otherwise, the last action in the buffer would be act after step and would be replaced by the default action in reset, as the last act would in fact never be applied (see a2 in the previous figure, imagining that a1 keeps being applied instead of arbitrary actions being applied by wait and reset, which in this case should be much shorter / near-instantaneous).

It is worth thinking about this if you wish to replace the action buffer with, e.g., recurrent units of a neural network while artificially splitting a non-episodic problem into finite episodes.

The time granularity achievable with rtgym depends on your Operating System.

Typically, on a high-end machine, Windows should be fine for time steps larger than 20 milliseconds, Linux can deal with time steps one order of magnitude shorter, and you can probably achieve even finer-grained control using a real-time OS. We provide benchmarks for Windows and Linux in the following Figures.

On Windows, precision is limited by the time granularity of the sleep call.

For instance, on Windows 11, a 20ms (50Hz) target in rtgym will in fact result in the following distribution of individual time step durations:

The duration of a 20ms time step in Windows is 20ms on average, but the actual duration of individual time steps constantly oscillates between 15ms and 31ms.

This is because the time granularity of the sleep call in Windows is 16ms (regardless of the target duration).

On Linux, rtgym can operate at a much higher frequency.

For instance, using the same machine as the previous Windows experiment, rtgym easily achieves a time step duration of 2ms (500Hz) on Linux:

(Note: capture refers to the duration elapsed between two subsequent calls to the get_obs_rew_terminated_info method or your RealTimeGymInterface implementation, and control refers to the duration elapsed between two subsequent calls to its send_control method.)

This tutorial will teach you how to implement a Real-Time Gym environment for your custom application, using rtgym.

The complete script for this tutorial is provided here.

Implementing a Gymnasium environment on a real system is not straightforward when time cannot be paused between time-steps for observation capture, inference, transfers and actuation.

Real-Time Gym provides a python interface that enables doing this with minimal effort.

In this tutorial, we will see how to use this interface in order to create a Gymnasium environment for your robot, video game, or other real-time application. From the user's point of view, this environment will work as Gymnasium environments usually do, and therefore will be compatible with many readily implemented Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms.

First, we need to install the Real-Time Gym package.

Run the following in a terminal or an Anaconda prompt:

pip install rtgymThis will install Real-Time Gym and all its dependencies in your active python environment.

Now that Real-Time Gym is installed, open a new python script.

You can import the RealTimeGymInterface class as follows:

from rtgym import RealTimeGymInterfaceThe RealTimeGymInterface is all you need to implement in order to create your custom Real-Time Gym environment.

This class has 6 abstract methods that you need to implement: get_observation_space, get_action_space, get_default_action, reset, get_obs_rew_terminated_info and send_control.

It also has a wait and a render methods that you may want to override.

We will implement them all to understand their respective roles.

You will of course want to implement this on a real system and can directly adapt this tutorial to your application if you feel comfortable, but for the needs of the tutorial we will instead be using a dummy remote controlled drone with random communication delays.

Import the provided dummy drone as follows:

from rtgym import DummyRCDroneA dummy RC drone can now be created:

rc_drone = DummyRCDrone()The dummy drone evolves in a simple 2D world. You can remotely control it with commands such as:

rc_drone.send_control(vel_x=0.1, vel_y=0.2)Note that whatever happens next will be highly stochastic, due to random delays.

Indeed, the velocities vel_x and vel_y sent to the drone when calling send_control will not be applied instantaneously.

Instead, they will take a duration ranging between 20 and 50ms to reach the drone.

Moreover, this dummy drone is clever and will only apply an action if it is not already applying an action that has been produced more recently.

But wait, things get even more complicated...

This drone sends an updated observation of its position every 10ms, and this observation also travels for a random duration ranging between 20 and 50ms.

And since the observer is clever too, they discard observations that have been produced before the most recent observation available.

In other words, when you retrieve the last available observation with

pos_x, pos_y = rc_drone.get_observation(), pos_x and pos_y will be observations of something that happened 20 to 60ms is the past, only influenced by actions that were sent earlier than 40 to 110 ms in the past.

Give it a try:

from rtgym import DummyRCDrone

import time

rc_drone = DummyRCDrone()

for i in range(10):

if i < 5: # first 5 iterations

vel_x = 0.1

vel_y = 0.5

else: # last 5 iterations

vel_x = 0.0

vel_y = 0.0

rc_drone.send_control(vel_x, vel_y)

pos_x, pos_y = rc_drone.get_observation()

print(f"iteration {i}, sent: vel_x:{vel_x}, vel_y:{vel_y} - received: x:{pos_x:.3f}, y:{pos_y:.3f}")

time.sleep(0.05)In this code snippet, we control the dummy drone at about 20Hz. For the 5 first iteration, we send a constant velocity control, and for the 5 last iterations, we ask the dummy drone to stop moving. The output looks something like this:

iteration 0, sent vel: vel_x:0.1, vel_y:0.5 - received pos: x:0.000, y:0.000

iteration 1, sent vel: vel_x:0.1, vel_y:0.5 - received pos: x:0.000, y:0.000

iteration 2, sent vel: vel_x:0.1, vel_y:0.5 - received pos: x:0.003, y:0.015

iteration 3, sent vel: vel_x:0.1, vel_y:0.5 - received pos: x:0.008, y:0.040

iteration 4, sent vel: vel_x:0.1, vel_y:0.5 - received pos: x:0.012, y:0.060

iteration 5, sent vel: vel_x:0.0, vel_y:0.0 - received pos: x:0.016, y:0.080

iteration 6, sent vel: vel_x:0.0, vel_y:0.0 - received pos: x:0.020, y:0.100

iteration 7, sent vel: vel_x:0.0, vel_y:0.0 - received pos: x:0.023, y:0.115

iteration 8, sent vel: vel_x:0.0, vel_y:0.0 - received pos: x:0.023, y:0.115

iteration 9, sent vel: vel_x:0.0, vel_y:0.0 - received pos: x:0.023, y:0.115

Process finished with exit code 0The commands we sent had an influence in the delayed observations only a number of time-steps after they got sent.

Now, you could do what some RL practionners naively do in such situations: use a time-step of 1 second and call it a day. But of course, this would be far from optimal, and not even really Markovian.

Instead, we want to control our dummy drone as fast as possible. Let us say we want to control it at 20 Hz, i.e. with a time-step of 50ms. To keep it simple, let us also say that 50ms is an upper bound of our inference time.

What we need to do in order to make the observation space Markovian in this setting is to augment the available observation with the 4 last sent actions. Indeed, taking into account one time-step of 50ms for inference and the transmission delays, the maximum total delay is 160ms, which is more than 3 and less than 4 time-steps (see the Reinforcement Learning with Random Delays paper for more explanations).

Note that this will be taken care of automatically, so you don't need to worry about it when implementing your RealTimeGymInterface in the next section.

Create a custom class that inherits the RealTimeGymInterface class:

from rtgym import RealTimeGymInterface, DummyRCDrone

import gymnasium.spaces as spaces

import gymnasium

import numpy as np

class MyRealTimeInterface(RealTimeGymInterface):

def __init__(self):

pass

def get_observation_space(self):

pass

def get_action_space(self):

pass

def get_default_action(self):

pass

def send_control(self, control):

pass

def reset(self, seed=None, options=None):

pass

def get_obs_rew_terminated_info(self):

pass

def wait(self):

passNote that, in addition to the mandatory abstract methods of the RealTimeGymInterface class, we override the wait method and implement a __init__ method.

The latter allows us to instantiate our remote controlled drone as an attribute of the interface, as well as other attributes:

def __init__(self):

self.rc_drone = DummyRCDrone()

self.target = np.array([0.0, 0.0], dtype=np.float32)The get_action_space method returns a gymnasium.spaces.Box object.

This object defines the shape and bounds of the control argument that will be passed to the send_control method.

In our case, we have two actions: vel_x and vel_y.

Let us say we want them to be constrained between -2.0m/s and 2.0m/s.

Our get_action_space method then looks like this:

def get_action_space(self):

return spaces.Box(low=-2.0, high=2.0, shape=(2,))RealTimeGymInterface also requires a default action.

This is to initialize the action buffer, and optionally to reinitialize it when the environment is reset.

In addition, send_control is called with the default action as parameter when the Gymnasium environment is reset.

This default action is returned as a numpy array by the get_default_action method.

Of course, the default action must be within the action space that we defined in get_action_space.

With our dummy RC drone, it makes sense that this action be vel_x = 0.0 and vel_y = 0.0, which is the 'stay still' control:

def get_default_action(self):

return np.array([0.0, 0.0], dtype='float32')We can now implement the method that will send the actions computed by the inference procedure to the actual device.

This is done in send_control.

This method takes a numpy array as input, named control, which is within the action space that we defined in get_action_space.

In our case, the DummyRCDrone class readily simulates the control-sending procedure in its own send_control method.

However, just so we have something to do here, DummyRCDrone.send_control doesn't have the same signature as RealTimeGymInterface.send_control:

def send_control(self, control):

vel_x = control[0]

vel_y = control[1]

self.rc_drone.send_control(vel_x, vel_y)Now, let us take some time to talk about the wait method.

As you know if you are familiar with Reinforcement Learning, the underlying mathematical framework of most RL algorithms, called Markov Decision Process, is by nature turn-based.

This means that RL algorithms consider the world as a fixed state, from which an action is taken that leads to a new fixed state, and so on.

However, real applications are of course often far from this assumption, which is why we developed the rtgym framework.

Usually, RL theorists use fake Gymnasium environments that are paused between each call to the step() function.

By contrast, rtgym environments are never really paused, because you simply cannot pause the real world.

Instead, when calling step() in a rtgym environment, an internal procedure will ensure that the control passed as argument is sent at the beginning of the next real time-step.

The step() function will block until this point, when a new observation is retrieved.

Then, step() will return the observation so that inference can be performed in parallel to the next time-step, and so on.

This is convenient because the user doesn't have to worry about these kinds of complicated dynamics and simply alternates between inference and calls to step() as they would usually do with any Gymnasium environment. However, this needs to be done repeatedly, otherwise step() will time-out.

Yet, you may still want to artificially 'pause' the environment occasionally, e.g. because you collected a batch of samples, or because you want to pause the whole experiment.

This is the role of the wait method.

By default, wait is a no-op, but you may want to override this behavior by redefining the method:

def wait(self):

self.send_control(np.array([0.0, 0.0], dtype='float32'))You may want your drone to land when this function is called for example.

Note that you generally do not want to customize wait when "reset_act_buf" is True in the rtgym configuration dictionary.

In this tutorial this will be the case, thus we keep the default behavior:

def wait(self):

passThe get_observation_space method outputs a gymnasium.spaces.Tuple object.

This object describes the structure of the observations returned from the reset and get_obs_rew_terminated_info methods of our interface.

In our case, the observation will contain pos_x and pos_y, which are both constrained between -1.0 and 1.0 in our simple 2D world.

It will also contain target coordinates tar_x and tar_y, constrained between -0.5 and 0.5.

Note that, on top of these observations, the rtgym framework will automatically append a buffer of the 4 last actions, but the observation space you define here must not take this buffer into account.

In a nutshell, our get_observation_space method must look like this:

def get_observation_space(self):

pos_x_space = spaces.Box(low=-1.0, high=1.0, shape=(1,))

pos_y_space = spaces.Box(low=-1.0, high=1.0, shape=(1,))

tar_x_space = spaces.Box(low=-0.5, high=0.5, shape=(1,))

tar_y_space = spaces.Box(low=-0.5, high=0.5, shape=(1,))

return spaces.Tuple((pos_x_space, pos_y_space, tar_x_space, tar_y_space))We can now implement the RL mechanics of our environment (i.e. the reward function and whether we consider the task terminated in the episodic setting), and a procedure to retrieve observations from our dummy drone.

This is done in the get_obs_rew_terminated_info method.

For this tutorial, we will implement a simple task.

At the beginning of each episode, the drone will be given a random target. Its task will be to reach the target as fast as possible.

The reward for this task will be the negative distance to the target.

The episode will end whenever an observation is received in which the drone is less than 0.01m from the target.

Additionally, we will end the episode if the task is not completed after 100 time-steps.

The task is easy, but not as straightforward as it looks. Indeed, the presence of random communication delays and the fact that the drone keeps moving in real time makes it difficult to precisely reach the target.

get_obs_rew_terminated_info outputs 4 values:

obs: a list of all the components of the last retrieved observation, except for the action bufferrew: a float that is our rewardterminated: a boolean that tells whether the episode is finished (always False in the non-episodic setting)info: a dictionary that contains any additional information you may want to provide

For our simple task, the implementation is fairly straightforward.

obs contains the last available coordinates and the target, rew is the negative distance to the target, terminated is True when the target has been reached, and since we don't need more information info is empty:

def get_obs_rew_terminated_info(self):

pos_x, pos_y = self.rc_drone.get_observation()

tar_x = self.target[0]

tar_y = self.target[1]

obs = [np.array([pos_x], dtype='float32'),

np.array([pos_y], dtype='float32'),

np.array([tar_x], dtype='float32'),

np.array([tar_y], dtype='float32')]

rew = -np.linalg.norm(np.array([pos_x, pos_y], dtype=np.float32) - self.target)

terminated = rew > -0.01

info = {}

return obs, rew, terminated, infoWe did not implement the 100 time-steps limit here because this will be done later in the configuration dictionary.

Note: obs is a list although the observation space defined in get_observation_space must be a gymnasium.spaces.Tuple.

This is expected in rtgym.

However, the inner components of this list must agree with the inner observation spaces of the tuple.

Thus, our inner components are numpy arrays here, because we have defined inner observation spaces as corresponding gymnasium.spaces.Box in get_observation_space.

Finally, the last mandatory method that we need to implement is reset, which will be called at the beginning of each new episode.

This method is responsible for setting up a new episode in the episodic setting.

In our case, it will randomly place a new target.

reset returns an initial observation obs that will be used to compute the first action, and an info dictionary where we may store everything else.

A good practice is to implement a mechanism that runs only once and instantiates everything that is heavy in reset instead of __init__.

This is because RL implementations will often create a dummy environment just to retrieve the action and observation spaces, and you don't want a drone flying just for that.

Replace the __init__ method by:

def __init__(self):

self.rc_drone = None

self.target = np.array([0.0, 0.0], dtype=np.float32)

self.initialized = FalseAnd implement the reset method as follows:

def reset(self, seed=None, options=None):

if not self.initialized:

self.rc_drone = DummyRCDrone()

self.initialized = True

pos_x, pos_y = self.rc_drone.get_observation()

self.target[0] = np.random.uniform(-0.5, 0.5)

self.target[1] = np.random.uniform(-0.5, 0.5)

return [np.array([pos_x], dtype='float32'),

np.array([pos_y], dtype='float32'),

np.array([self.target[0]], dtype='float32'),

np.array([self.target[1]], dtype='float32')], {}We have now fully implemented our custom RealTimeGymInterface and can use it to instantiate a Gymnasium environment for our real-time application.

To do this, we simply pass our custom interface as a parameter to gymnasium.make in a configuration dictionary, as illustrated in the next section.

Now that our custom interface is implemented, we can easily instantiate a fully fledged Gymnasium environment for our dummy RC drone.

This is done by loading the rtgym DEFAULT_CONFIG_DICT and replacing the value stored under the "interface" key by our custom interface:

from rtgym import DEFAULT_CONFIG_DICT

my_config = DEFAULT_CONFIG_DICT

my_config["interface"] = MyRealTimeInterfaceWe also want to change other entries in our configuration dictionary:

my_config["time_step_duration"] = 0.05

my_config["start_obs_capture"] = 0.05

my_config["time_step_timeout_factor"] = 1.0

my_config["ep_max_length"] = 100

my_config["act_buf_len"] = 4

my_config["reset_act_buf"] = FalseThe "time_step_duration" entry defines the duration of the time-step.

The rtgym environment will ensure that the control frequency sticks to this clock.

The "start_obs_capture" entry is usually the same as the "time_step_duration" entry.

It defines the time at which an observation starts being retrieved, which should usually happen instantly at the end of the time-step.

However, in some situations, you will want to actually capture an observation in get_obs_rew_terminated_info and the capture duration will not be negligible.

In such situations, if observation capture is less than 1 time-step, you can do this and use "start_obs_capture" in order to tell the environment to call get_obs_rew_terminated_info before the end of the time-step.

If observation capture is more than 1 time-step, it needs to be performed in a parallel process and the last available observation should be used at each time-step.

In any case, keep in mind that when observation capture is not instantaneous, you should add its maximum duration to the maximum delay, and increase the size of the action buffer accordingly. See the Reinforcement Learning with Random Delays appendix for more details.

In our situation, observation capture is instantaneous. Only its transmission is random.

The "time_step_timeout_factor" entry defines the maximum elasticity of the framework before a time-step times-out.

When it is 1.0, a time-step can be stretched up to twice its length, and the framework will compensate by shrinking the durations of the next time-steps.

When the elasticity cannot be maintained, the framework breaks it for one time-step and warns the user.

This might happen after calls to reset() depending on how you implement the reset method of the interface.

However, if this happens repeatedly in other situations, it probably means that your inference time is too long for the time-step you are trying to use.

The "ep_max_length" entry is the maximum length of an episode.

When this number of time-steps have been performed since the last reset(), truncated will be True.

In the non-episodic setting, set this to np.inf.

The "act_buf_len" entry is the size of the action buffer. In our case, we need it to contain the 4 last actions.

Finally, the "reset_act_buf" entry tells whether the action buffer should be reset with default actions when reset() is called.

In our case, we don't want this to happen, because calls to reset() only change the position of the target, and not the dynamics of the drone.

Therefore we set this to False.

We are all done! Instantiating our Gymnasium environment is now as simple as:

env = gymnasium.make("real-time-gym-v1", config=my_config)We can use it as any usual Gymnasium environment:

def model(obs):

return np.clip(np.concatenate((obs[2] - obs[0], obs[3] - obs[1])) * 20.0, -2.0, 2.0)

terminated, truncated = False, False

obs, info = env.reset()

while not (terminated or truncated):

act = model(obs)

obs, rew, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(act)

print(f"rew:{rew}")Optionally, you can also implement a render method in your RealTimeGymInterface.

This allows you to call env.render() to display a visualization of your environment.

Implement the following in your custom interface (you need opencv-python installed and to import cv2 in your script) :

def render(self):

image = np.ones((400, 400, 3), dtype=np.uint8) * 255

pos_x, pos_y = self.rc_drone.get_observation()

image = cv2.circle(img=image,

center=(int(pos_x * 200) + 200, int(pos_y * 200) + 200),

radius=10,

color=(255, 0, 0),

thickness=1)

image = cv2.circle(img=image,

center=(int(self.target[0] * 200) + 200, int(self.target[1] * 200) + 200),

radius=5,

color=(0, 0, 255),

thickness=-1)

cv2.imshow("PipeLine", image)

if cv2.waitKey(1) & 0xFF == ord('q'):

returnYou can now visualize the environment on your screen:

def model(obs):

return np.array([obs[2] - obs[0], obs[3] - obs[1]], dtype=np.float32) * 20.0

terminated, truncated = False, False

obs, info = env.reset()

while not (terminated or truncated):

env.render()

act = model(obs)

obs, rew, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(act)

print(f"rew:{rew}")

cv2.waitKey(0)rtgym provides a way of timing the important operations happening in your real-time environment.

In order to use the benchmark option, set the corresponding entry to True in the configuration dictionary:

my_config['benchmark'] = TrueThe provided benchmarks will contain means and average deviations of critical operations, such as your inference duration and observation retrieval duration.

These metrics are estimated through Polyak averaging.

The Polyak factor sets the dampening of these metrics.

A value close to 0.0 will be precise but slow to converge, whereas a value close to 1.0 will be fast and noisy.

This factor can be customized:

my_config['benchmark_polyak'] = 0.2The benchmarks can then be retrieved at any time from the environment once it is instantiated. They are provided as a dictionary of tuples. In each tuple, the first value is the average, and the second value is the average deviation:

import pprint # pretty print for visualizing the dictionary nicely

print("Environment benchmarks:")

pprint.pprint(env.benchmarks())The output looks like this:

Environment benchmarks:

{'inference_duration': (0.014090990135653982, 0.0012176857248554194),

'join_duration': (0.03710293826222041, 0.006481136920225911),

'retrieve_obs_duration': (8.012583396852672e-05, 0.0001397626015969312),

'send_control_duration': (0.000634083523134701, 0.0005238185602401273),

'step_duration': (0.037439853824566036, 0.006698605131647715),

'time_step_duration': (0.051359845765767326, 0.006117140690528808)}Here, our inference duration is 0.014 seconds, with an average deviation of 0.0012 seconds.

Importantly, note that retrieving observations and sending controls is almost instantaneous because the drone's communication delays do not influence these operations.

The time-step duration is 0.05 seconds as requested in the configuration dictionary.

Most of this duration is spent joining the rtgym thread, i.e. waiting for the previous time-step to end.

Therefore, we could increase the control frequency here.

However, note that doing this would imply using a longer action buffer.

The time-step's maximum elasticity defines the tolerance of your environment in terms of time-wise precision.

It is set in the configuration dictionary as the "time_step_timeout_factor" entry.

This can be any value > 0.0.

When this is set close to 0.0, the environment will not tolerate uncertainty in your custom interface.

When this is e.g. 0.5, a time-step will be allowed to overflow for half its nominal duration.

This overflow will be compensated in future time-steps.

Usually, you don't want to set this value too high, because time-wise variance is probably what you want to avoid when using rtgym.

However, in some special cases, you may actually want your time-steps to overflow repeatedly.

In particular, if your inference duration is very small compared to your observation retrieval duration, you may want to set your observation retrieval time at the end of the time-step (default behavior), so that observation retrieval always overflows for almost a whole time-step.

This is because inference will happen directly after the observation is captured, and the computed action will be applied at the beginning of the next time-step. You may want this to be as tight as possible.

In such situation, keep in mind that inference must end before the end of this next time-step, since the computed action is to be applied there. Otherwise, your time-steps will timeout.

In rtgym, the default action is sent when reset() is called.

This is to maintain the real-time flow of time-steps during reset transitions.

It may happen that you prefer to repeat the previous action instead, for instance because it is hard in your application to implement a no-op action.

To achieve this behavior, you can simply replace the default action of your environment via set_default_action with the action that you want being sent, right before calling reset():

env.set_default_action(my_new_default_action)

obs, info = env.reset()

# Note: alternatively, you can set the "last_act_on_reset" entry to True in your configuration.

# This would make reset() send the last action instead of the default action.

# In rtgym, when terminated or truncated is True, the action passed to step() is not sent.

# Setting "last_act_on_reset" to True sends it on the subsequent reset().

# Think thoroughly before setting this to True, as this might not ne suitable.

# In Real-Time RL, the last action of an episode has no effect in terms of reward.

# Thus, it may be entirely random depending on your training algorithm.All contributions to this project are welcome. To contribute, please submit a pull request that includes your name in the Contributors list.

- Yann Bouteiller

Many thanks to our sponsors for their support!