Materials for the session organized by the CoDArchLab in the Institute of Archaeology at University of Cologne (20/6/2022).

This exercise introduces the basic concepts and workflow of Agent-based modelling (ABM), as it is used in archaeology. More specifically, it covers the prototyping of a conceptual model into a working simulation model, the 'refactoring' of code (cleaning, restructuring, optimizing), the re-use of published model parts and algorithms, the exploration of alternative designs, and the use of geographic, climatic and archaeological data to apply the model to a specific case study. The tutorial offers implementation examples of path cost analysis, hydrological and land productivity modelling, network dynamics, and cultural evolution.

This tutorial uses NetLogo, a flexible well-established modelling platform known for its relatively low-level entry requirements in terms of programming experience. It has been particularly used in social sciences and ecology for research and educational purposes.

- Preparation

- Introduction

- Block A

- Definition of the target system

- Conceptual model

- NetLogo basics

- NOTE: other platforms/languages

- Test-drive: creating a "pond" terrain

- Step 0: Drawing a blue circle

- Step 1a: De-composing "magic numbers"

- Step 1b: Parameterizing

- Step 1c: Optimasing

- Step 2a: Pacing comments and line breaks

- Step 2b: Exploring alternative designs

- Step 2c: Colors and shades

- Step 3: Adding noise (stochasticity)

- Step 4b: design alternatives

- Step 4c: keeping design alternatives

- Step 4d: patch neighborhood

- Step 4e: iterative structures

- Step 4f: printing event messages

- Step 5: refactoring (again)

- Block B

- Block C

To prepare for the tutorial, you only need to:

- Download and install the latest version of NetLogo. The operating system-specific installation files are found here: https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/download.shtml

- Download or 'clone' the contents of this repository into a local folder. Select

in the top right of the repository page in GitHub, and choose one of the options given.

in the top right of the repository page in GitHub, and choose one of the options given.

This is a brief overview of agent-based modelling (ABM), primarily focusing on how it is used in archaeology.

To better contextualise ABM, we start by positioning this modelling approach in relation to others used by researchers in archaeology and keen disciplines. We then describe ABM's central concepts, including what makes it often more intuitive and adequate for representing certain phenomena, particularly social interactions, yet paradoxically being more complex and unpredictable than other simulation models.

As the term is used in science, we can define models as representations of a system, as a composite of elements and their relationships. Mathematical models are simply more advanced in their logical definition through the process of formalisation. The informal or less formal models are those that are defined only through natural language speech (e.g., in a live discussion), text (e.g., in an article or book), or through certain graphical pieces (e.g., infographics, diagrams).

Despite this distinction, there is no genuine opposition between models with different levels of formalisation. Mathematical formalisation is mainly used to implement and test the logic models stated less formally. Among the advantages of mathematical formalisation, the most important are univocity (i.e., things have a single definition) and commensurability (i.e. things can be measured or counted). These properties set formal models apart from models formulated purely with natural languages, among other things, allowing for a significant improvement in the robustness of our reasoning. Keep in mind, though: formalisation can also harm the intelligibility of our models, because they move away from natural languages.

Within the large family of mathematical models, ABM models lie typically within a category that can be characterised as explicative or mechanistic. Explicative models are focused on an explanation, expressing processes through realistic relationships between variables, often including assumptions. Non-explicative or descriptive mathematical models are used more strictly to describe, reproduce or extrapolate the relationship between variables (i.e., most statistical models). The latter models are about patterns or trends in data, while the former are about the mechanisms underlying data, at least as we can define them based on our current understanding of the phenomena's domain.

The line between these categories is blurred and confounded by many models and model users. Notice, for example, that the very term "explanation" is widely used in non-mechanistic ways (e.g., when it is said that the educational level of a person explains that person's income). However, the bulk of models on each side is considerable, and ABM models, in particular, have traits that are undeniably linked to the formulation of mechanisms.

To help understand this distinction, we can think about one of the most simple and popular descriptive models used today: the linear regression model. Every regression model is a generalised equation based on a geometric pattern, a straight line in the case of the linear regression:

y = a + b·x

Geometric representation of a linear regression model

A linear regression model has two variables, x and y, which define two orthogonal dimensions, and two parameters, a and b, which determine the value of y when x = 0 and the tangent of the angle formed by the line with the x dimension. These are "meaningless" (semantically empty) in the model design, even if we deliberately choose x as the "independent" variable, despite how they are interpreted at a higher level of analysis.

To put an archaeological example, imagine we have two variables measured in a collection of sites, the estimated maximum area and the count of potsherds on the surface. Imagine that we can define a regression model that states a positive correlation exists between them. Assuming our dataset is large enough and not radically biased, we could probably interpret that built area influences (i.e., causes, in a weak sense) the abundance of potsherds on the surface. It would not be necessarily illogical to conclude this. Yet, the relationship described in the model is ultimately a correlation (no archaeologist would think that one is directly causing the other).

The trend expressed by the linear model is but a "hint" of the mechanisms that are or could be postulated to explain it. Any hypotheses about the reason behind the correlation must be formulated outside the model, before or after its creation, for instance, by combining it with a natural language model. Thus, a descriptive model is inherently incomplete as an analytic tool and remains trivial unless it is associated with an external explicative model, formal or informal.

A model that return the output given the input

A model that return the output given the input and the definition of a mechanism

Still, descriptive mathematical models have been proven to be very useful and are widely adopted. Consider that in the field of artificial intelligence, the success of the descriptive models encompassed by machine learning have pushed aside other modelling approaches that uses programmed or procedural rules, from which ABM has branched. Within the exploration of data-driven methods, some scholars have even started to question the concept of "explanation" itself, posing that it might be a well-hidden fallacy of human cognition. On the other hand, it is still debatable how much human understanding can come from descriptive models alone.

In contrast with other mechanistic and dynamic mathematical modelling approaches, ABM seeks to represent a phenomenon by explicitly modeling its parts. Therefore, ABM involves the expectation that the phenomenon at the macro-level emerges (can be deduced) from the dynamics at the micro-level. Moreover, ABM implies that the parts, the agents, constitute 'populations', i.e., they share common properties and behavioral rules. The 'agency' behind the term 'agent' also implies that these parts have certain autonomy with respect to each other and the environment, which justifies simulating their behavior at an individual level.

In practice, 'autonomy' often translates as the agents' ability to take action, move, decide, or even think and remember. Decision-making is a central aspect of agents and most agent designs can be sufficiently expressed as flowcharts. Nevertheless, agent-based models also include entities that are technically agents (on the terms of multi-agent systems), but lack many of such abilities or are not considered real/material discrete entities. The most common case is to represent space sectors as agents fixed to unique positions in a grid to facilitate the implementation of distributed spatial processes (e.g., the growth of vegetation dependent on local factors). In NetLogo, this type of agent is predefined as patches and is extensively used in models in ecology and geography.

Compared to other modeling and simulation approaches, ABM is more intuitive but also more complex. For example, the Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model in ecology is a pair of differential equations that are relatively simple and conceptually straightforward. They essentially express the following dynamics:

assumption: prey population grows based on unspecified resources (intrinsic growth rate)

more prey → more food for predators, so more predators will survive and reproduce

more predators → more prey will be killed, so less prey will survive and reproduce

less prey → less food for predators, so fewer predators will survive and reproduce

fewer predators → less prey will be killed, so more prey will survive and reproduce

more prey → more food ... (the cycle begins again)

Example of Lotka Volterra dynamics

The same model can also be implemented with ABM (see the comparison in NetLogo's Model Library Wolf-Sheep Predation (Docked Hybrid)). The ABM implementation requires many additional specifications on how predator and prey agents should behave individually. Even though it is not strictly necessary to represent the core mechanism, ABM variations of the Lotka-Volterra model often aim to include more complexity. In the case of the Wolf-Sheep model mentioned, there is an explicit account of the base resource (i.e., the prey of the prey), named grass, which is implemented as a property of spatial units. These additional specifications normally help the model be more intuitive and realistic but also significantly complicate the model design and implementation, even though generating similar aggregate dynamics as the equation-based version (i.e., oscillation harmony between prey and predator populations).

NetLogo user interface running the Wolf-Sheep Predation model

Another important and distinctive aspect of agent-based models is that they are unavoidably stochastic, i.e., at least some processes are fed by random sequences.

By definition, the order in which agents of a type perform their processes should not be predefined and, overall, should not be the same followed every iteration of the model. Thus, the only unbiased way of scheduling processes in ABM is to randomize all distributed sequences. This is (usually) not the case in models based on differential/difference equations, where the equations calculating variables are solved following a particular fixed order.

Methodologically, introducing randomness is a way of accounting for the entire spectrum of possibilities, whenever a certain aspect of the model is undertheorized or cannot be controled in real scenarios. More importantly, it is justified whenever the modeler believes that the intended behavior is independent of a specific value or order.

For those with no previous experience with computer science: note that "random" for a computer is not like "rolling dices". We are getting values of a preordered sequence presumably unrelated to the process at hand. The programs creating these sequences are called pseudorandom number generator or RNG, for short. Sequences will be different every time we run our program (i.e., simulation), unless we preset the RNG using a specific 'seed', an integer often spanning a massive range of positive and negative numbers. Setting a particular RNG seed is, in fact, good practice, and helps enforce the reproducibility of simulation results.

This technique is also helpful in creating variation within a population of agents or between the global conditions of simulation runs. Such a thing is accomplished by drawing the values of variables from probability distributions, defined through hyperparameters (e.g., drawing the age of individuals in a classroom from a normal distribution defined by two parameters, age_mean and age_standardDeviation). Unfortunately, a typical bad practice is not exposing such hyperparameters, having these 'hard-coded' as if their value were an intrinsic part of the model and thus the mechanisms it represents. This bad coding element, often called "magic numbers", can and should be addressed during model implementation (see Verification-refactoring cycle).

Last, another significant advantage of ABM is that it can include parts (algorithms, submodels) that belong to other modelling approaches. For example, we can quickly devise a model where a population of agents runs in parallel with a full-fledged Dynamic Systems model through a set of difference equations. Commonly, ABM models are ensembles created with parts that technically are not ABM. This is why some ABM modellers and modelling platforms use terms like "multiparadigm modelling" or "hybrid modelling", which is more precise for many cases. Unfortunately, these were not adopted more widely and "agent-based modelling" continues to be the most common term, particularly in archaeology.

ABM has conceptual roots and applications in other fields relatively early, hand-to-hand with the history of computer science. However, this methodology was formed as it is today and introduced more broadly into social sciences only in the 1990s.

ABM has been exceptionally well accepted by archaeologists, given its pre-adaptation towards distributed and stochastic processes. Most phenomena of interest for archaeology can be represented with ABM, to the satisfaction of archaeologists. Other modelling and simulation approaches (e.g., Dynamic Systems) were and still are used but often encounter great resistance due to their higher abstraction and simplification.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of topics that have or could have been investigated with ABM in archaeology:

- Physico-chemical dynamics

- Artefact production: e.g., chaîne opératoire, authorship, material transformations.

- Site formation: e.g., artefact and structure distributions, preservation, deposition, stratification and post-depositional processes, sample bias.

- Ecological dynamics

- Climate patterns: e.g., seasonality, regional variations, climate change.

- Hydrological dynamics: e.g., water availability.

- Vegetation: e.g., crop dynamics.

- Non-human animal behaviour: e.g., herd behaviour, animal husbandry, transhumance.

- Anthropological dynamics

- Individuals: e.g., pedestrian dynamics, metabolic scavenging, kinship, micro-economics, mating and marriage, reproduction, cognition (memory, rationality and learning), individual-to-individual cooperation and competition, social learning, norms.

- Groups: e.g., households, organisations, group-to-group cooperation and competition, prestige, reward and punishment, cultural transmission.

- Settlements: e.g., population dynamics, migration, macro-economics, trade, urbanisation, cultural evolution, settlement patterns, land use, politogenesis.

- Regional to global: e.g., center-periphery dynamics, genetic and cultural diffusions.

ABM flexibility is also very much appreciated by researchers involved in archaeology, given that it is a discipline both historically and thematically positioned in-between other disciplines in the overlap of the so-called natural and artificial worlds. An ABM model can handle multiple layers of entities and relationships, allowing it to integrate entire models under the same hood.

The same advantage was exploited by disciplines such as ecology, environmental science, and geography. The approach used by these disciplines has been the main motor driving the development of models in archaeology for more than two decades. Some authors have named this transdisciplinary framework as the research of socio-ecological systems (SES), which has been defined in close relationship with the more general complexity science approach. One of the first cases of public success of ABM in archaeology, the Artificial Anasazi model (Axtell et al. 2002), emerged from this approach and as a collaboration between researchers orbiting the Santa Fe Institute.

Despite its positive influence in pushing the field forward, the SES approach has also limited the diversity of scope and theory used with ABM in archaeology. ABM under SES aligns particularly well, for example, with research questions related to landscape and environmental archaeology and formulated from a perspective biased towards processualism. This tutorial is no exception. To the potential "new-blood" in this field, I recommend always keeping the mind open to all questions and theoretical frameworks, particularly those you are already invested in.

ABM in archaeology has been a prolific field, despite being still enclosed in a small community. Here, we will only cover a small part of the field, specifically from my perspective. For a broader introduction to the multitude of contributions in this field, I refer to any of the many introductory references included later in this section (see References - Introductions to ABM and Social Simulation). I recommend the recent textbook by Romanowska, Wren & Crabtree (2021), which also includes many practical exercises in NetLogo, using a programming style and philosophy significantly different from this tutorial.

In the remaining sections of the Introduction, we will go deeper in describing the workflow of ABM. First, we lay out this workflow as it is commonly declared by practitioners, as a sequence of well-ordered steps that may be iterated in a revision cycle. Then, we introduce a few elements 'behind the scene' that stretch the 'steps' metaphor to its limits. We then review a few practical recommendations that, hopefully, will aid future ABM modellers. These include the verification-refactoring cycle in programming, the use of modular code, and the importance of remaining explorative while designing a model.

Modelling with ABM can be divided into steps, most of which are identified by the community of practitioners as either normative or recommended phases of model development. With minor variations, these are also recognised in other simulation and non-simulation modelling approaches.

The steps are:

Definition of the research question and phenomenon. To define a research question and the phenomena involved, we must think in terms of systems, identifying and defining a set of elements we deem relevant and their interrelationships. In this initial step, the key is to delimitate the target system, within which external, undefined factors do not overly determine the interaction of elements. Here, we must decide on what is relevant for us and set aside the rest. Ideally, we should move to the next step only once we have a hypothetical mechanism to focus on, formulated roughly but in detail enough so we can formalise it later. We will call this our conceptual model.

Design. Designing a model is essentially to find a formal definition able to represent the phenomena, as we have defined in the previous step. In this step, we go from a vague text description of the natural system we observe and its expected dynamics to a mathematical or algorithmic representation of the artificial system we want to build. At this stage, it is critical to define our model's main variables, including any inputs and outputs. The latter will be particularly important to how simulation results can be compared to empirical data to validate the model. During model design, our conceptual model is formalised progressively, ideally up to the point where implementation is made immediate.

Implementation. To implement the model is to effectively write down our model design as a piece of software (i.e., through programming). While other mathematical models could remain unimplemented, ABM models are hardly useful if not able to be solved through computer simulation. However, a model implementation carries much extra baggage, and many possible implementations exist for the same model. Therefore, modellers and their audience must differentiate between the model and its implementation.

Verification. To verify a model implementation, we run a series of tests on the model code and compare the results with our expectations as model designers. If we wrote a fragment of code to calculate "2 + 2" expecting "4", we should get "4" after running it. On the other hand, verifying a model (not its implementation) can only be done by running an implementation, which we assume is correctly representing the model. If our model states that "2 + 2 = 4", and our implementation returns "4", then we would conclude that the logic behind our model is correct.

Validation. To validate a model is to iteratively match the conditions of our model (assumptions, parameter values, etc.) to measurable conditions in the targeted system and the results of simulations to equivalent variables measured in the targeted system. ABM modellers often regard validation as an extra, lengthy process, usually separable from the tasks involved in defining, implementing, and exploring a model. Validation is never an absolute term: it will depend on the amount of data available and the specific criteria chosen. A validated model is not a "correct" model, nor a model failing validation is a "useless" model.

Furthermore, a few authors, myself included, also like to highlight two additional steps that are generally not acknowledged:

Understanding. The modeller must understand the model, know the variety of dynamics it can generate, and be aware of its limitations regarding the representation of the target system.

Documenting. The understanding obtained by the modeller at one point is of little use to others and, eventually, her or himself in the long-term future. To ensure that such an understanding is passed through, we must invest significant time in documenting the model's conceptual design and source code. Note that this is not equivalent to an academic publication, especially because most scientific journals push for a greater emphasis on the results rather than the bits and pieces of simulation models.

However, building an ABM model is, in practice, a process that is significantly more complicated than the steps listed above. There are many shortcuts, such as finding a model or piece of code that can save months of work, but, more often, there are obstacles, fallbacks, and failures that test ABM modellers and the teams of researchers working with them. Some modellers (myself included) have characterized this as a 'reiterative' process, often drawing diagrams showing these steps in well-planned cycles. However, it might be more exact to lose the walking metaphor altogether.

The first problematic situation that comes to mind is, of course, the "technical issues". Developing ABM models requires a set of skills that are rare and hard to obtain and maintain meanwhile doing other research tasks. Probably the most prominent skill of a modeller is programming, which involves conceptual abstraction and certain agility with the software being used. The latter is made even more relevant when the software used is poorly documented or requires a particular setup upon installation. This is undoubtedly the first entry toll of the ABM community for researchers in the humanities and social sciences. Still, the hardships on this side usually are surpassable with continuous training, support from more experienced modellers, and choosing the right software. Still, it is undeniably a long-term commitment.

Unfortunately, issues related to ABM go deeper than code and software. For example, during the model design process, researchers might need to ask inconvenient and trivial questions about the phenomena represented, which raise a surprising amount of controversy and doubt and can even challenge some of the core assumptions behind a study. In archaeology, this may come as aspects that are considered out of the scope of empirical research due to the limiting nature of archaeological data compared to disciplines that focus on contemporary observations (e.g., anthropology, sociology, geography). Should an archaeological ABM model include mechanisms that cannot be validated by archaeological data (at least not in the same sense as experimental sciences)? This is probably the most important unresolved question in this field and possibly the one most responsible for hindering the use of ABM in archaeology.

These complications can be considered problems and opportunities, depending on if and how they are eventually resolved. In some cases, the difficulty will present a new idea or approach. In contrast, in other cases, dealing with it might cost valuable time and delay the research outcomes beyond any external deadlines (e.g., project funding, dissertation submission). The tutorial below is presented in the spirit of safeguarding modellers in training from being stopped short by some obstacles while pursuing their research agendas using ABM.

Before jumping into coding, let us go over three general strategies that can offer a way out to at least some of the problems mentioned here. These strategies are: refactoring regularly, enforcing modularity and being explorative.

By definition, refactoring means that your code change but remains capable of producing the same result. Refactoring encompasses all tasks aiming to generalize the code, make it extendable, and also make it cleaner (more readable) and faster.

However, there is a trade-off between these three goals. For example, replacing default values with calculations or indirect values will probably increase processing time. In practice, this trade-off is irrelevant until your model is very complex, populated (many entities), or must be simulated for many different conditions. I recommend always being attentive to the readability, commentary, and documentation of your code. Assuming you are interested in creating models for academic discussion (i.e., science rather than engineering), the priority is to communicate your models to others.

There are many actions in code that can be considered refactoring. Too many for us to enumerate here. Probably the best and more educational approach is to encounter examples of practices, both good and bad, think about them, and try to do better. In this sense, we will go over several examples along with the tutorial that hopefully will illustrate when and how you should refactor your model code.

One of the most critical aspects related to refactoring is code modularity. The so-called Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) has been established in software engineering and serves as an excellent guiding principle for building complex code.

In software like ABM models, modularity also has application at a higher level, in the form of submodels. Creating models as assembles of submodels enables researchers to focus on their areas of interest and expertise without necessarily over reducing the complexity of everything else.

ABM has been, and still is, often critisised for being a too complex and arbitrary approach in its aim and domain. Truthfully, ABM models tend to overgrow in detail regarding certain aspects while bluntly simplifying other elements. This is primarily a combined effect of the internal limitations of the modellers and their teams (time, budget, expertise, etc.) and the lack of opportunities for code reuse. Modularity offers an exit to this.

Modules can be built as original contributions, implemented from published model specifications, reimplemented from another programming language, or taken and modified as code snippets. We will encounter all these cases later on in this tutorial.

There are many sources of potential modules. The most direct source is, of course, your relevant bibliography. Despite the number of models and modellers, the likely scenario is that the modules you need are still not available as usable implementations. In such cases, you might need to translate model specifications, with a varied level of formalisation, into a working piece of code. The less formalise is the original contribution, the harder will be the challenge. Thankfully, there are a few alternatives where modules can be taken almost without extra coding.

When using NetLogo, we first count with the Netlogo's Models Library, a collection of implementation examples classified by discipline and domain. All files are included in the installation of NetLogo and can be accessed through File > Models Library.

The wide community of NetLogo users also hosts two extra libraries, the NetLogo User Community Models and the NetLogo Modelling Commons, where modellers from different disciplines can upload their models, and share and discuss them with others.

A similar initiative was created from modellers more strongly associated with the SES framework. Today named as CoMSES Model Library, former openABM, it holds almost the same amount of models as NetLogo Modelling Commons and, despite being cross-platform, the majority of entries are implemented in NetLogo. CoMSES also hosts a curated bibliographic database, which can help search subject-related models. Even though massive, it does not represent all ABM and related modelling being done worldwide. CoMSES relies on voluntary work, as most scientific associations do, and its updates rely on a relatively small community.

More recently, a growing group of researchers involved in ABM in archaeology, including myself, have created an initiative, Network for Agent-based modelling of Socio-ecological Systems in Archaeology (NASSA), whose principal goal is to create and maintain a public library of modules (i.e., formatted as modules). Hopefully, this library's first version will be available sometime later this year. You are welcome to join our activities and help create this community asset (write me an e-mail!).

The last general recommendation to be made about doing ABM is: to be explorative. As mentioned, some have critisised ABM for being too speculative and arbitrary. Yes, ABM models often require many specifications to work, some of which escape the modeller's expertise entirely. In front of this, we can either avoid ABM altogether or accept it, going the proverbial extra mile in making most "free decisions" based on a deeper study of possible design alternatives.

Similar to how we can use stochasticity, creating and exploring design alternatives is always a good idea to better understand our conceptual model's weak points. Observing the differences in dynamics generated by those alternatives will help us decide how to define those uncertain areas further while reducing the risk of unconsciously running over important modelling decisions. In the tutorial, we will illustrate a few strategies for implementing and handling design alternatives.

A short disclaimer before we start: the approach used here for conceptual modelling and model documentation is not considered a standard in the ABM community. In the bibliography, you will find many other recommendations and examples, particularly those converging into the practices closer to Computer Science and Ecology. For example, many consider a necessary standard to be the Unified Modeling Language (UML). The Overview-Design-Details (ODD) protocol is also quite strongly advocated by ABM practitioners (see On the ODD protocol in References).

After years of creating and reviewing ABM models, I would argue that these are not as useful or applicable as claimed, and the time spent in learning these could be better used to improve one's programming skills. However, I believe that any student of ABM should know about these proposed standards and then judge and decide for themselves. I only use simple text and free-styled graphs for this tutorial while trying to enforce the most clarity in the code possible.

This introductory session on ABM in archaeology is neither complete nor the necessary standard. The following materials can help delve deeper into the subject, experiment with various perspectives and cases, and possibly build a specialised profile in this field.

Manson, Steven M., Shipeng Sun, and Dudley Bonsal. 2012. ‘Agent-Based Modeling and Complexity’. In Agent-Based Models of Geographical Systems, edited by Alison J. Heppenstall, Andrew T. Crooks, Linda M. See, and Michael Batty, 125–39. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8927-4_7.

Epstein, Joshua M. 2006. Generative Social Science: Studies in Agent-Based Modeling. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bonabeau, Eric. 2002. ‘Agent-Based Modeling: Methods and Techniques for Simulating Human Systems’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (SUPPL. 3): 7280–87. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.082080899.

Epstein, Joshua M., and Robert Axtell. 1996. Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up. Brookings Institution Press. https://www.brookings.edu/book/growing-artificial-societies/.

Romanowska, Iza, Colin D. Wren, and Stefani A. Crabtree. 2021. Agent-Based Modeling for Archaeology. Electronic. SFI Press. https://doi.org/10.37911/9781947864382.

Graham, Shawn, Neha Gupta, Jolene Smith, Andreas Angourakis, Andrew Reinhard, Ellen Ellenberger, Zack Batist, et al. 2020. ‘4.4 Artificial Intelligence in Digital Archaeology’. In The Open Digital Archaeology Textbook. Ottawa: ECampusOntario. https://o-date.github.io/draft/book/artificial-intelligence-in-digital-archaeology.html.

Romanowska, Iza, Stefani A. Crabtree, Kathryn Harris, and Benjamin Davies. 2019. ‘Agent-Based Modeling for Archaeologists: Part 1 of 3’. Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (2): 178–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2019.6.

Davies, Benjamin, Iza Romanowska, Kathryn Harris, and Stefani A. Crabtree. 2019. ‘Combining Geographic Information Systems and Agent-Based Models in Archaeology: Part 2 of 3’. Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (2): 185–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2019.5.

Crabtree, Stefani A., Kathryn Harris, Benjamin Davies, and Iza Romanowska. 2019. ‘Outreach in Archaeology with Agent-Based Modeling: Part 3 of 3’. Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (2): 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2019.4.

Cegielski, Wendy H., and J. Daniel Rogers. 2016. ‘Rethinking the Role of Agent-Based Modeling in Archaeology’. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (March): 283–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAA.2016.01.009.

Wurzer, Gabriel, Kerstin Kowarik, and Hans Reschreiter. 2015. Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation in Archaeology. Edited by Gabriel Wurzer, Kerstin Kowarik, and Hans Reschreiter. Advances in Geographic Information Science. Vol. 7. Advances in Geographic Information Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00008-4.

Lake, Mark W. 2014. ‘Trends in Archaeological Simulation’. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 21 (2): 258–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-013-9188-1.

Costopoulos, André, and Mark W. Lake, eds. 2010. Simulating Change: Archaeology into the Twenty-First Century. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Isaac Ullah (2022, June 01). “The Archaeological Sampling Experimental Laboratory (tASEL)” (Version 1.1.1). CoMSES Computational Model Library. Retrieved from: https://www.comses.net/codebases/addd3c54-d89a-4773-a639-8bf19bcf59ea/releases/1.1.1/

Angourakis, Andreas, Jennifer Bates, Jean-Philippe Baudouin, Alena Giesche, Joanna R. Walker, M. Cemre Ustunkaya, Nathan Wright, Ravindra Nath Singh, and Cameron A. Petrie. 2022. ‘Weather, Land and Crops in the Indus Village Model: A Simulation Framework for Crop Dynamics under Environmental Variability and Climate Change in the Indus Civilisation’. Quaternary 5 (2): 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat5020025.

Andreas Angourakis. (2021). Two-Rains/indus-village-model: The Indus Village model development files (May 2021) (v0.4). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4814255.

Angelos Chliaoutakis (2020, April 09). “AncientS-ABM: Agent-Based Modeling of Past Societies Social Organization” (Version 1.0.0). CoMSES Computational Model Library. Retrieved from: https://www.comses.net/codebases/50cf5d2a-0f37-4d4d-84e0-715e641180d9/releases/1.0.0/

Angourakis, Andreas, Matthieu Salpeteur, Verònica Martínez Ferreras, Josep Maria Gurt Esparraguera, Verònica Martínez Ferreras, and Josep Maria Gurt Esparraguera. 2017. ‘The Nice Musical Chairs Model: Exploring the Role of Competition and Cooperation Between Farming and Herding in the Formation of Land Use Patterns in Arid Afro-Eurasia’. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24 (4): 1177–1202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-016-9309-8.

Madella, Marco, Bernardo Rondelli, Carla Lancelotti, Andrea L. Balbo, Débora Zurro, Xavier Rubio Campillo, and Sebastian Stride. 2014. ‘Introduction to Simulating the Past’. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 21 (2): 251–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-014-9209-8.

Rubio Campillo, Xavier, Jose María Cela, and Francesc Xavier Hernàndez Cardona. 2012. ‘Simulating Archaeologists? Using Agent-Based Modelling to Improve Battlefield Excavations’. Journal of Archaeological Science 39 (2): 347–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.020.

Wilkinson, Tony J., John H. Christiansen, Jason Alik Ur, M. Widell, and Mark R. Altaweel. 2007. ‘Urbanization within a Dynamic Environment: Modeling Bronze Age Communities in Upper Mesopotamia’. American Anthropologist 109 (1): 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2007.109.1.52.

Kohler, Timothy A., and Sander van der Leeuw. 2007. The Model-Based Archaeology of Socionatural Systems. Santa Fe: AdvanceResearch Press.

Premo, L. S. 2006. ‘Agent-Based Models as Behavioral Laboratories for Evolutionary Anthropological Research’. Arizona Anthropologist 17: 91–113.

Graham, Shawn, and J. Steiner. 2009. ‘TravellerSim: Growing Settlement Structures and Territories with Agent-Based Modeling’. In Digital Discovery: Exploring New Frontiers in Human Heritage. CAA 2006. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. Proceedings of the 34th Conference, Fargo, United States, April 2006, edited by Jeffrey T. Clark and Emily M. Hagemeister. Budapest: Archaeolingua. https://electricarchaeology.ca/2009/10/16/travellersim-growing-settlement-structures-and-territories-with-agent-based-modeling-full-text/.

Axtell, Robert L., Joshua M. Epstein, Jeffrey S. Dean, George J. Gumerman, Alan C. Swedlund, Jason Harburger, Shubha Chakravarty, Ross Hammond, Jon Parker, and Miles Parker. 2002. ‘Population Growth and Collapse in a Multiagent Model of the Kayenta Anasazi in Long House Valley’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (Supplement 3): 7275–79. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.092080799.

Kohler, Professor and Chair Department of Anthropology Timothy A., Timothy A. Kohler, George J. Gumerman, and Director Arizona State Museum and Research Professor of Anthropology George G. Gumerman. 2000. Dynamics in Human and Primate Societies: Agent-Based Modeling of Social and Spatial Processes. Oxford University Press.

Winterhalder, Bruce. 1997. ‘Gifts given, Gifts Taken: The Behavioral Ecology of Nonmarket, Intragroup Exchange’. Journal of Archaeological Research 5 (2): 121–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02229109.

Erwin, Harry R. 1997. ‘The Dynamics of Peer Polities’. In Time, Process, and Structured Transformations, edited by Sander E. Van der Leeuw and James McGlade, 57–97. One World Archaeology 26. London: Routledge.

Rihll, T. E., and A. G. Wilson. 1991. ‘Modelling Settlement Structures in Ancient Greece: New Approaches to the Polis’. In City and Country in the Ancient World. Routledge.

Grimm, Volker, Uta Berger, Finn Bastiansen, Sigrunn Eliassen, Vincent Ginot, Jarl Giske, John Goss-Custard, et al. 2006. ‘A Standard Protocol for Describing Individual-Based and Agent-Based Models’. Ecological Modelling 198 (1–2): 115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLMODEL.2006.04.023.

Grimm, Volker, Uta Berger, Donald L. DeAngelis, J. Gary Polhill, Jarl Giske, and Steven F. Railsback. 2010. ‘The ODD Protocol: A Review and First Update’. Ecological Modelling 221 (23): 2760–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLMODEL.2010.08.019.

Müller, Birgit, Friedrich Bohn, Gunnar Dreßler, Jürgen Groeneveld, Christian Klassert, Romina Martin, Maja Schlüter, Jule Schulze, Hanna Weise, and Nina Schwarz. 2013. ‘Describing Human Decisions in Agent-Based Models – ODD + D, an Extension of the ODD Protocol’. Environmental Modelling & Software 48 (October): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSOFT.2013.06.003.

https://github.com/ArchoLen/The-ABM-in-Archaeology-Bibliography

Hart, Vi, and Nicky Case. n.d. ‘Parable of the Polygons’. Parable of the Polygons. Accessed 24 May 2022. http://ncase.me/polygons.

Izquierdo, Luis R., Segismundo S. Izquierdo, and William H. Sandholm. 2019. Agent-Based Evolutionary Game Dynamics. https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/agent-based-evolutionary-game-dynamics/.

Banning, Frederik. 2022. ‘Julia ♥ ABM #1: Starting from Scratch’. Julia Community. 2022. https://forem.julialang.org/fbanning/series/1.

In Block A, we will start by defining the target system based on a case study and composing a conceptual model based on a previous model (PondTrade). We will then advance to implementation, learning the basics of NetLogo and applying it, going over the initial steps of developing the PondTrade model.

In this tutorial, we will proceed as if our goal were to address with ABM the case study and some of the research questions of the following publication:

Paliou, Eleftheria, and Andrew Bevan. 2016. ‘Evolving Settlement Patterns, Spatial Interaction and the Socio-Political Organisation of Late Prepalatial South-Central Crete’. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 42 (June): 184–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.04.006.

- Case study: settlement interaction and the emergence of hierarchical settlement structures in Prepalatial south-central Crete

- Phenomena to represent: cycles of growth and collapse (i.e., fluctuations in the scale of site occupation). Focus on site interconnectivity and its relationship with settlement size.

- Main assumption: topography, transport technology, exchange network, settlement size, wealth, and cultural diversity are intertwined in a positive feedback loop.

- Dynamics we expect and want to explore: the long-term consolidation of central sites and larger territorial polities.

Our objective using ABM is to delve deeper into the expectations of our current knowledge about the growth of settlements and the formation of local polities in this crucial period, preluding the Minoan palatial institution. As in the original paper, we will need to assume a series of conditions and behaviour rules, considered valid for this context, given historical and anthropological parallels.

With site distributions and artefactual classifications, archaeology offers an opportunity for us to estimate aspects such as population density and economic and cultural interactions. However, to relate the socio-ecological past to the material evidence in the present, we must inevitably use an explanatory model. There are many published models relevant to this topic, several already mentioned by Paliou & Bevan (2016). However, few are formalised to some extent, and fewer are available as reusable implementations. Luckily, some of these are ABM models (you may consult them in the References above).

As mentioned, ABM is particularly hungry for specifications, many of which are not even dreamed of by the average archaeologist. In this tutorial, we will try to maintain an intermediate level of model abstraction, avoiding many details that would normally be included in the ABM-SES approach in archaeology.

Later, you can compare ABM with other approaches, such as the gravity models referenced in the original study. Hopefully, you will gain an intuitive perception of the advantages and caveats of ABM in front of more analytical approaches, in particular regarding the study of settlement patterns and interactions.

When creating your first conceptual model, I recommend starting from scratch with the first intuition that comes to mind. After later scrutiny, its logic structure may be oversimplified, incomplete, or faulty. However, it would most likely represent the main elements of an informal model that you and other researchers share. Relying on an informed guess to start model development is the best remedy for the "blank page panic". It will also help you avoid overthinking and overworking what should be a mere preliminary sketch of the model.

Said this, we might still suffer when trying to jump-start the modelling process. Even if (or maybe especially when) a sizeable interdisciplinary team is involved, such is often the case in ABM-related projects.

To complement the initial "brainstorming" of conceptual models, modellers will often search and review models already published on related subjects, considering if these could be reused, at least as an inspiration.

Keeping yourself posted about the ABM community may give you an edge. Unfortunately, academic publishing has become a saturated media, and it is relatively hard to be updated about specific types of research, such as ABM models, which are often spread in many specialised publications. Public model repositories, such as CoMSES and initiatives like the modular library from NASSA may aid you greatly in this task. But, ultimately, finding a relevant model will depend on your skills in Internet search and the attention others have put to preparing and publishing their models.

Regarding our case study, there are many models that we could adopt as a start point or as a potential source of modules. ABM models in archaeology built from the SES framework are likely to be adaptable to our case study, however, with variable success regarding the relevance of its results to our main question. Most models in this category are indeed focused on elements of landscape archaeology, particularly settlement patterns and emerging social complexity in prehistoric to early-historic periods. Among the most prominent candidates, we could count, for example, Artificial Anasazi and its variations, MERCURY and its extensions, MayaSim, and especially AncientS-ABM (Chliaoutakis 2019), which has been designed for Minoan Bronze Age and applied to different parts of Crete.

However, given that this is a tutorial, we will be using another, much simpler model: the PondTrade model.

The PondTrade model was designed by me in 2018 to facilitate learning ABM and is designed mainly for archaeology and history.

The PondTrade model represents mechanisms that link cultural integration and economic cycles caused by the exchange of materials (“trade”) between settlements placed in a heterogeneous space (“pond”). The PondTrade design intentionally includes several aspects commonly used by other ABM models in archaeology and social sciences, such as multiple types of agents, the representation of a so-called “cultural vector”, procedural generation of data, network dynamics, and the reuse of published submodels and algorithms.

The Pond Trade model and all its versions were developed by myself, Andreas Angourakis, and are available for download in this repository: https://github.com/Andros-Spica/PondTrade. Note that the content of PondTrade/README.md is a previous and incomplete version of what we will cover here in Block A. It has also been used in Graham et al. 2020 as one of several exercises on ABM, and the text in this tutorial relies partially in the content of that chapter.

A similar model, TravellerSim, was presented by Graham & Steiner (2008), who were revisiting an older non-ABM model (Rihll & Wilson 1991, pp. 59-95), even though one was not based on the other. All three, and indeed many more, coincide in the "informal formulation" of the core mechanism, rooted in economic theory, relating the size of settlements to how they are interconnected.

A side-note: such a situation, where similar mechanisms are modelled from scratch several times by different researchers, is, in fact, prevalent in the ABM community. There is a growing number of publications and models spreading over many specialised circles, which do not always cover all details about model implementation. Meanwhile, there is still no adequate logistical support for orderly sharing and searching for models across disciplines, despite the efforts made by CoMSES. The primary mission of NASSA is to offer a long-term solution to this problem.

Since our research question fits quite well with the scope of the PondTrade model, we will use it to approach our case while also learning about ABM and NetLogo by following its development steps.

The Pond Trade model core idea is inspired by the premise that the settlement economy's size depends on the volume of materials exchanged between settlements for economic reasons (i.e. ‘trade’). The "economic" size of settlements is an overall measure of, e.g., population size, the volume of material production, built surface, etc. The guiding suggestion was that economy size displays a chaotic behavior as described by chaos theory (apparently "random" oscillations) because of the shifting nature of trade routes, explicitly concerning maritime and fluvial routes as opportunities for transportation.

The initial inspiration for a model design may be theoretically profound, empirically based, or well-connected to discussions in the academic literature. However, the primary core mechanism of a model must narrow down to a straightforward, intelligible process. In this case, the focus is to represent a positive feedback loop between settlement size and the trade volumes coming in and out, which can be described as follows:

Core mechanism:

- Traders choose their destination trying to maximize the value of their cargo by considering settlement size and distance from their base settlement;

- An active trade route will increase the economic size of settlements at both ends

- An increase in size will increase trade by:

- Making a settlement more attractive to traders from other settlements

- Allowing the settlement to host more traders.

- An active trade route will increase the cultural similarity between two settlements through the movement of traders and goods from one settlement to the other (cultural transmission)

Elements (potentially entities):

- settlements

- traders

- terrain

- routes

- goods

Preliminary rules:

- Coastal settlements of variable size around a rounded water body (“pond”)

- Traders travel between the settlements

- Traders travel faster or slower depending on the terrain

- Once in their base settlement, traders evaluate all possible trips and choose the one with the greater cost-benefit ratio

- Traders carry economic value and cultural traits between the base and destination settlements

- Settlement size depends on the economic value received from trading

- The economic value produced in a settlement depends on its size

- The number of traders per settlement depends on its size

Targeted dynamics:

Settlements that become trade hubs will increase in size and have a greater cultural influence over their trade partners, though also receiving much of their aggregated influences

The display above might seem somewhat chaotic and vague, but it intends to represent one of the best-case scenarios in terms of the conciseness of the initial conceptual model. There are no golden rules, good-for-all schemes or "right words" at this stage. You should start from your (or your team's) knowledge and hypotheses and move these into implementation, where you may revise them. In my opinion, you should not limit your ideas beforehand to external frameworks (e.g., some of the points required in the ODD).

Still, we count here on the second layer of the conceptual model, which allows us to have an overall plan of the implementation steps.

The first implementation steps in the Pond Trade tutorial (Test-drive: creating a "pond" terrain) addresses the creation of a "geography" where settlements are placed around a water body. This gives us the context for having a differential cost in travelling between settlements (assuming that travel over water is easier/faster), and allows us to work with the concept of route, which is not a trivial task from the programming perspective.

We will cover those steps with special attention since they offer us an opportunity to address many fundamental aspects of programming in NetLogo:

- Step 0: drawing a blue circle

- Step 1: replacing “magic numbers”

- Step 2: refactoring

- Step 3: adding noise

- Step 4: design alternatives and printing to the console

- Step 5: refactoring and organizing

To pace the complexity of modelling process, we organise the further development of the PondTrade conceptual model in two tiers. The first tier will aim to cover only some aspects of our initial formulation:

Mechanisms:

- ↑ global level of productivity → ↑ settlement production

- ↑ number of settlements → ↓ distance between settlements

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ settlement production → ↑ trade flow from/to settlement → ↑ settlement size

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ number of traders based in settlement → ↑ trade flow from/to settlement → ↑ settlement size

- ↑ trade attractiveness of route A to B → ↑ trade flow A to B

- ↑ distance A to B → ↓ trade attractiveness A to B

- ↑ size B → ↑trade attractiveness A to B

- ↑ trade flow A to B → ↑ trade flow B to A

Pond Trade conceptual model at start (first tier)

Track the paths made by the arrows in our diagram. Notice that we have drawn a system with at least two positive feedback loops (cycles with "+" arrows), one mediated by the production and the other by the number of traders.

Expected dynamics: differentiation of settlements (size) according to their relative position

To achieve this, we will go through steps 6 to 9 (Block B - First-tier model):

- Step 6: agent types

- Step 7: agent AI

- Step 8: adding feedback loops I

- Step 9: adding feedback loops II

To reach the full version of the PondTrade model, we also need to address the aspects related to cultural transmission and evolution:

Mechanisms:

- ↑ global undirected variation in culture → ↑ or ↓ cultural similarity A and B (cultural drift)

- ↑ trade flow A to B → ↑ cultural similarity A and B (cultural integration)

- ↑ global cultural permeability → ↑ cultural similarity A and B, if A and B are trading (acceleration of cultural integration)

Pond Trade conceptual model at start (second tier)

Expected dynamics: cultural integration as the outcome of exchange network dynamics

To achieve this, we will go through steps 10 to 13 (Block B - Second-tier model):

- Step 10: cultural vectors

- Step 11: trait selection

- Step 12: interface statistics

- Step 13: output statistics

In addition to the core mechanism, we must consider another aspect to better approach our case study.

The PondTrade model has several caveats. Like any other model, it is incomplete and greatly simplifies those aspects of reality that we chose not to prioritise. One of the most significant simplifications is that each settlement's production is only dependent on a general term of productivity, independent of the land accessible to its inhabitants.

This limitation is not a significant problem if we are dealing with a straightforward terrain, like in the original PondTrade where we only differentiate between land and water. However, we eventually aim to apply the model to a specific region and use the available geographical and archaeological data. Therefore, we lay out a potential expansion of the original PondTrade, which will enable us to factor in the diversity regarding the land productivity around settlements.

Mechanisms:

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ settlement territory

- ↑ settlement territory → ↑ production (of land)

- ↑ productivity (of land) → production (of land)

- ↑ production (of land) → ↑ production (of settlement)

Expanded Pond Trade conceptual model at start

Notice that, with this expansion, we are again introducing a positive feedback loop or splitting the one that already involves production. This time, however, instead of relying on a global parameter, we are regulating the process through a location-specific value (i.e., productivity of land).

Expected dynamics: production is 'grounded', i.e., dependent on each settlement catchment area size and productivity

To implement this expansion, we will need to complicate the original implementation of PondTrade further. To keep our code under control, we will consolidate a few modular implementations to bring them together into a new expanded PondTrade model centered on our case study. We will need modules covering the following:

- Load and prepare spatial data (raster and vector GIS layers)

- Load and prepare time-series data

- Calculate best routes between settlements based on spatial data

- Calculate productivity of land-based on spatial and time-series data

We will go through these modules and the implementation of the expanded PondTrade in Block C.

Once a minimum conceptual model is defined, we should use caution when attempting our first implementation. A relatively simple model may still correspond to code that can be very difficult to control and understand. Simulation models are very sensitive to the presence of feedback loops. You will notice in the tutorial that the positive feedback loops present in the conceptual model are not included until the most basic and predictable aspects are properly defined and their behaviors verified.

NOTE: In the explanation below I'm using

<UPPERCASE_TEXT>to express the positions in the code to be filled by the name of entities, variables, and other elements, depending on the context. For instance,<COLOR> <FRUIT>would represent many possible phrases, such as "red apple", "brown kiwi", etc.

As a preamble, important to anyone without previous experiences with programming languages, the very first thing one can do in NetLogo is give oneself a bit of encouragement. In the NetLogo interface, go to the bottom area named 'Command Center' and type the following in the empty field on the right of 'observer>' and press Enter:

You can do it!The console prints:

ERROR: Nothing named YOU has been defined.

Oops! NetLogo still doesn't know "you". Or is it that it cannot understand you? Well let us get you two properly introduced...

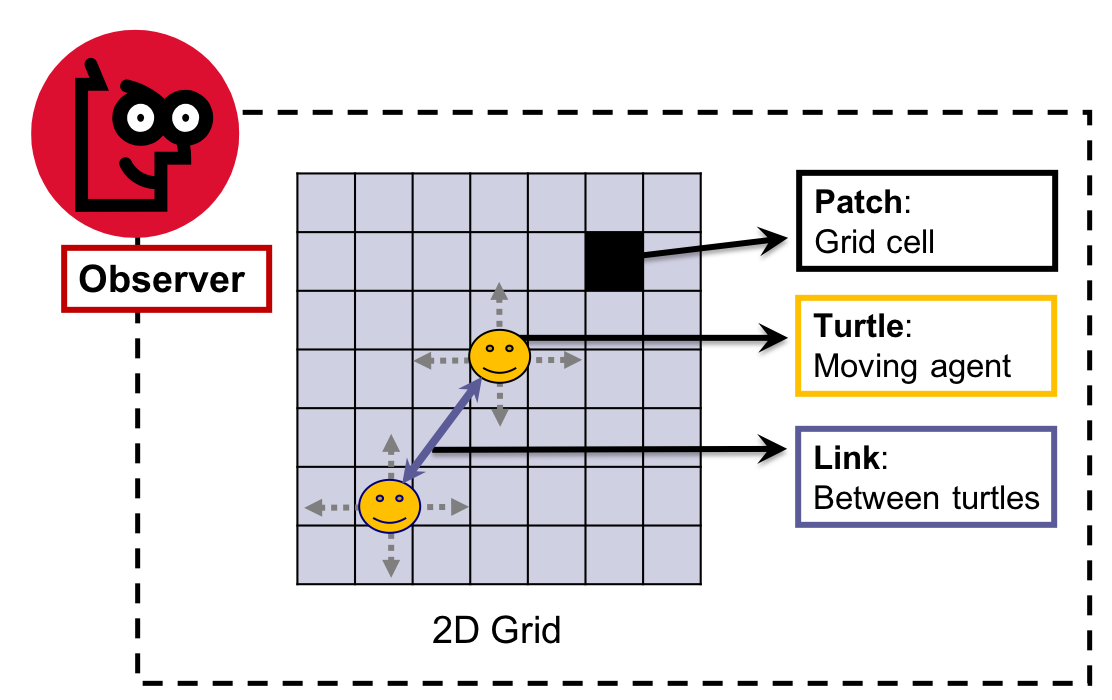

The (real) first thing one should learn about NetLogo, and most agent-based modeling systems, is that it handles mainly two types of entities/agents: patches, cells of a square grid, and turtles, which are proper "agents" (i.e., mobile, autonomous entities). Both entities have primitives (built-in, default properties), some of which can be modified by processes in your model. For example, you can't modify the position of a patch, but you can change its filling color.

NetLogo world and entities (Figure 2 in Izquierdo et al. 2019)

As seen in the figure above, NetLogo also includes a third type of entity, links, which has the particularity of describing a connection between two turtles and thus not having specific spatial coordinates of their own. We will deal with links later on, but for now we focus on the other entities, which are more commonly used in models.

All patches and turtles can be identified individually through primitives. Turtles have a unique numerical identifier (who) that is assigned automatically upon the creation of the turtle. Patches, in turn, have an unique combination of x and y integer coordinates in 2D space (pxcor and pycor), as they occupy each a single position in a grid (see Grid). To reference a specific turtle or patch:

turtle <WHO_NUMBER>

patch <PXCOR> <PYCOR>NetLogo allows you to define types of turtles as if it where a primitive, declarings its name as a breed:

breed [<BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL> <BREED_1_NAME_SINGULAR>]

breed [<BREED_2_NAME_PLURAL> <BREED_2_NAME_SINGULAR>]We can then use the plural or singular form of the breed name directly, instead of referring to the generic turtles.

<BREED_1_NAME_SINGULAR> <WHO_NUMBER>This is useful, of course, when there are more the one breedto be defined, so that they are easily distinguished and inteligible in the code.

Agents can be specifically selected also without considering their specific IDs. The one-of primitive offers a easy way to randomly select one agent (turtles and patches) from all (or a subset of all) agents of a given type.

one-of <BREED_2_NAME_PLURAL>

one-of patchesLast, we should keep in mind that turtles can be created and destroyed on-the-fly during simulations, while patches are created in the background upon initialisation, according to the model settings (e.g. grid dimensions), but never destroyed during simulation runs.

See NetLogo's documentation on agents for further details (https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/docs/programming.html#agents).

The most fundamental elements of NetLogo, as in any programming language, is variables. To assign a value to a variable we use the general syntaxis or code structure:

set <VARIABLE_NAME> <VALUE>While variable names are fragments of contiguous text following a naming convention (e.g. my-variable, myVariable, my_variable, etc.), values can be of the following data types:

- Number (e.g.,

1,4.5,1E-6) - Boolean (i.e.,

true,false) - String (effectively text, but enclosed by quote marks: e.g.,

"1","my value") turtles,patches(i.e., NetLogo's computation entities; see Entities)- AgentSet (a set of either

turtlesorpatches; see Entities) - List (a list enclosed in squared brakets with values of any kind separated by spaces: e.g.,

[ "1" 1 false my-agents-bunch ["my value" true 4.5] ])

Before we assign a value to a variable, we must declare its scope and name, though not its data type, which is only defined when assigning an specific value. Variable declaration is typically done at the first section of a model script and its exact position will depend on if it is stored globally or inside entities. These types of declarations follow their own structures:

globals [ <GLOBAL_VARIABLE_NAME> ]

turtles-own [ <TURTLE_VARIABLE_NAME> ]

<BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL>-own

[

<BREED_1_VARIABLE_1_NAME>

<BREED_1_VARIABLE_2_NAME>

]

patches-own [ <PATCHES_VARIABLE_NAME> ]As an exception to this general rule, variables can also be declared "locally" using the following syntaxis:

let <VARIABLE_NAME> <VALUE>As in other programming languages, having a variable declared locally means it is inside a temporary computation environment, such as a procedure (see below). Once the environment is closed, the variable is automatically discarded in the background.

As we will see examples further on, the values of variables can be transformed in different ways, using different syntaxis, depending on their type. Possibly the most straightforward case is to perform basic arithmetic operations over numerical variables, expressing equations. These can be writen using the special characters normally used in most programming languages (+, -, *, /, (, etc.):

set myVariable (2 + 2) * 10 / ((2 + 2) * 10)Notice that arithmetic symbols and numbers must be separated by spaces and that the order of operations can be structured using parentheses.

To help you read expressions that hold several operations, NetLogo allow line breaks, as long as these are placed after an operator (not a variable or value). The best and safer practice for this is to use parentheses abundantly to ensure the right sequence of operations is performed:

set myVariable (

(

(2 + 2) *

10

) / (

(2 + 2) *

10

)

)Additionally, as proper equations, such expressions in NetLogo will also accept variables names representing their current value. Equations can then serve to create far reaching dependencies between different parts of the model code:

set myVariable 2

set myOtherVariable 10

<...>

let myTemporaryVariable 2 * myVariable * myOtherVariable

set myVariable myTemporaryVariable / myTemporaryVariableIn NetLogo, any action we want to perform, that is not manually typed in the console, must be enclosed within a procedure that is declared in the model script (the text in 'Code' tab in the user interface). Similarly to 'functions' or 'methods' in other programming languages, a procedure is the code scripted inside the following structure:

to <PROCEDURE_NAME>

<PROCEDURE_CODE>

endAny procedure can be executed by typing <PROCEDURE_NAME> + Enter in the NetLogo's console at the bottom of the 'Interface' tab. The "Hello World" program, a typical minimum exercise when learning a programming language, correspond to the following procedure hello-world:

to hello-world

print "Hello World!"

endwhich generates the following "prints" in the console:

observer> hello-world

Hello World!

Procedures are particularly useful to group and enclose a sequence of commands that are semantically connected for the programmer. For example, the following procedure declares a temporary (local) variable, assigns to it a number as value, and prints it in the console:

to set-it-and-show-me

let thisVariableOfMine 42

print thisVariableOfMine

endProcedures can then be used elsewhere by writing its name (more complications to come). A procedure can be included as a step in another procedure:

to <PROCEDURE NAME>

<PROCEDURE_1>

<PROCEDURE_2>

<PROCEDURE_3>

...

endNetLogo's interface editor allows us to create buttons that can execute one or multiple procedures (or even a snippet of ad hoc code). The interface system is quite straightforward. First, at the top of the interface tab, click "Add" and select a type of element in the drop-down list. Click anywhere in the window below to place it. Select it with click-dragging or using the "Select" option in the right-click pop-up menu. You can edit the element by selecting "Edit", also in the right-click pop-up menu. For any doubts on how to edit the interface tab, please refer to NetLogo's documentation (https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/docs/interfacetab.html).

The code exemplifies how to create conditional rules according to predefined general conditions using if/else statements, which in NetLogo can be written as

iforifelse:

if (<CONDITION_1_IS_TRUE>)

[

<DO_ACTION_A>

]

ifelse (<CONDITION_2_IS_TRUE>)

[

<DO_ACTION_B>

]

[

<DO_ACTION_C>

]You can ask all or any subset of entities to perform specific commands by folowing the structure:

ask <ENTITIES>

[

<DO_SOMETHING>

]Commands inside the ask structure can be both direct variable operations and procedures. For instance:

ask <BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL>

[

set <BREED_1_VARIABLE_2> <VALUE>

<PROCEDURE_1>

<PROCEDURE_2>

<PROCEDURE_3>

]However, all variables referenced inside these structures must be properly related to their scope, following NetLogo's syntax. For example, an agent is only able to access the variable in another agent if it we use the folowing kind of structure:

ask <BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL>

[

print [<BREED_1_VARIABLE_2>] of <BREED_2_NAME_SINGULAR> <WHO_NUMBER>

]It is possible to select a subset of any set of entities through logic clauses to be checked separately for each individual entity. For example, to get all agents with a certain numeric property greater than a given threshold:

<TYPE_NAME_PLURAL> with [ <VARIABLE_NAME_1> > <THRESHOLD> ]When operating from the inside an ask command, we can also make sure to filter-out the agent currently performing the call, by using the primitive other:

ask <BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL>

[

ask other <BREED_1_NAME_PLURAL>

[

print <WHO_NUMBER>

]

]All this can be combined to form quite complex rules of behaviour, yet keeping itself generally readable:

to celebrate-birthday

ask people

[

if (today = my-birthday)

[

ask other people with [presents > 0]

[

give-present

]

]

]

endOne should spend some time understanding the grid structure and associated syntaxis. It is recommendable to consult the "settings" pop-up window in the "interface tab":

The settings pop-up window in NetLogo

The default configuration is a 33x33 grid with the position (0,0) at the center. Both dimensions and center can be easily edited for each particular model. Moreover, we can specify agents behavior at the borders by ticking the "wrap" options. Wrapping the world limits means that, for instance, under the default setting mentioned above, the position (-16,0) is adjacent to (16,0). In the console, we can "ask" the patch at (-16,0) to print its distance to the patch at (16,0), using the primitive function distance (https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/docs/dictionary.html#distance):

observer> ask patch -16 0 [ print distance patch 16 0 ]

1

Wrapping one dimension represents a cylindrical surface while wrapping two depicts a strange toroidal object (Donut!). Although this aspect is relatively hidden among the options, it can have great importance if spatial relations play any part in a model. So if you want your grid to represent a geographical map, make sure to untick the wrapping features.

Annotations or comments (i.e., text that should be ignored when executing the code) can be added to the code by using the structure:

<CODE>

; <FREE_TEXT>

<CODE>or

<CODE> ; <FREE_TEXT>One of the most useful resources of NetLogo's documentation is the dictionary that can be accessed in the "Help" menu. This is true at any moment throughout your learning curve; even when you know all primitives and built-in functions by heart. Moreover, all documentation is present with any copy of NetLogo, so it is fully available offline.

The dictionary is particularly useful whenever you are learning by example, as in our case. For instance, regarding the earlier mention of distance, you could have searched it in the dictionary directly. Whenever you find yourself reading NetLogo code with violet or blue words that you do not understand, take the habit of searching them in NetLogo's dictionary.

For more information consult NetLogo Programming Guide.

You are now introduced to NetLogo. However, please remember that ABM is not limited to this language and platform. It is highly recommended that you learn and practice with other programming languages to experience ABM models beyond NetLogo implementations.

Potentially, any programming language can be used to implement an ABM model. However, it is useful to count on specific support software in most cases. A few of the most relevant platforms and libraries to know about are: RePast, AnyLogic, Mesa, Agents.jl, and Pandora. See many others in this list by SWARM.org.

Now, let us make a minimum working example of all elements explained above while advancing towards the Pond Trade model prototype. Let us start with implementing a minimum base for the PondTrade model: the pond-like terrain.

For this section, I recommend starting your own NetLogo file (placed at the root directory of this repository) and writing the following steps progressively. Feel free to copy and paste whenever the code fragments become too long. If you run into any problems at the end of each step, you may check the corresponding complete script at the repository's root.

Inside a single procedure, called create-map, we order (ask) all patches to do something using the structure:

to create-map

ask patches

[

<DO_SOMETHING>

]

endNext, we use the syntax for setting variables (set <VARIABLE> <VALUE>) inside the procedure to change patches color to blue:

to create-map

ask patches

[

set pcolor blue

]

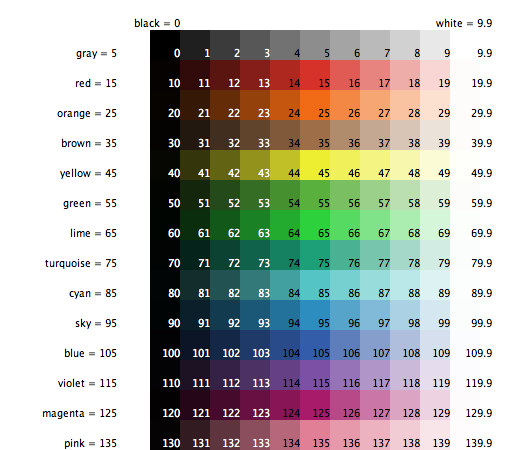

endNotice that both pcolor and blue are 'primitives', so they are automatically understood by NetLogo. Remember to consult NetLogo's Dictionary, if in doubt about such primitives. Color primitives such as blue or their numeric equivalent are shown in 'Color Swatches' inside the Tools menu tab.

Since we don't want all patches to have the same color, we need to build some structure that give different colors to patches depending on their position, so that a blue circle is draw.

Considering how to draw a circle, we need two bits of information: a center and a radius (respectively, O and R in the figure).

First, we must define a center. Because we won't use this information for anything else, we can declare and set a local variable (i.e., accessable only from its own context), using the syntax let <VARIABLE> <VALUE>. We define the center patch coordinates as (0,0):

to create-map

ask patches

[

let centralPatch patch 0 0

set pcolor blue

]

endWe can set a radius for our circle using a single numeric value, e.g. 5, expressed in patch widths:

to create-map

ask patches

[

let centralPatch patch 0 0

let minDistOfLandToCenter 5

set pcolor blue

]

endHowever, if we are passing a single absolute numeric value to be compared to a distance, the result will be sensitive to how large is our world grid. This is not wise, given that we might want to use this procedure in grids of different dimensions. Imagine that you are interested in changing the dimensions of the grid but want the circle to cover a similar proportion of it (e.g., adjusting the resolution of our map).

We can easily circunvent this code fragility by stepping-up its complexity. One alternative solution is to work with proportions of one of the grid dimensions, e.g. width (world-width). For the time being, we will set it to be half of half (a quater) of the width, since we have the circle positioned in the middle of the grid.

to create-map

ask patches

[

let centralPatch patch 0 0

let minDistOfLandToCenter round (0.5 * (world-width / 2))

set pcolor blue

]

endRunning this code will still not produce a blue circle. Rather, we are asking for all patches to paint themselve blue, no matter what the values of centralPatch or minDistOfLandToCenter.

To differenciate patches to be painted blue, we now use minDistOfLandToCenter for evaluating a criterium for a ifelse structure, finding out if a patch is inside or outside our circle. With this, we are ordering patches to paint themselves green or blue depending on if their distance to the center is less than a given value, i.e. minDistOfLandToCenter.

ifelse (distance centralPatch < minDistOfLandToCenter)

[

set pcolor blue ; water

]

[

set pcolor green ; land

]Now, the entire code for the create-map procedure is finally doing what we expected, drawing a blue circle over a green background:

to create-map

ask patches [

; set central patch

let centralPatch patch 0 0

; set minimum distance to center depending on world width

let minDistOfLandToCenter round (0.5 * (world-width / 2))

ifelse (distance centralPatch < minDistOfLandToCenter)

[

set pcolor blue ; water

]

[

set pcolor green ; land

]

]

endThe code we just created has several fixed arbitrary values (the coordinates of the centralPatch, the values used to calculate minDistOfLandToCenter). It is good enough for us to draw a particular blue circle, but it is insufficient to draw other types of blue circle. Of course, the code will never be able to draw anything, if we are not programming it to do it. For instance, the colors blue and green are also magic numbers, but we are hardly interest in having them as parameters. We must generalize but also compromise, accepting that there will be possibilities that are not covered by our model.

First, is there any case where the patch 0 0 is not the one at the center of the grid? Imagine that you don't like to have negative coordinates in your model. Go to "Settings" and modify the "location of origin" to be at the corner. Now, test the create-map procedure:

Not at all what we are looking for! To correct this behavior, we must calculate the center coordinates, depending on the ranges or sizes of the grid width and height, whatever its configuration. Therefore, we must replace 0 with the calculation minimum + range / 2 for both x and y coordinates:

let centralPatch patch (min-pxcor + floor (world-width / 2)) (min-pycor + floor (world-height / 2))We use the floor function to obtain the round lower grid position when the range is an odd number. Because this calculation uses only NetLogo primitives, you can test this by printing it in the console in any NetLogo model. It will return the central patch given your grid settings:

observer> show patch (min-pxcor + floor (world-width / 2)) (min-pycor + floor (world-height / 2))

observer: (patch 16 16)Now, regarding minDistOfLandToCenter, we could simply bring it as a parameter to be set in the interface instead of hard-coded (e.g. as a slider). This would be a better design, but we still would have a potential problem. Maybe you do not want the grid to be squared (e.g., 33x33), but rectangular (e.g., 100x20) instead. This is what you would get: