NANNY STATE makes it simple to build dynamic, state-based web apps in vanilla JS.

- SIMPLE - build interactive user-interfaces with just a few lines of code.

- FAST - automatic page renders that are blazingly fast.

- MINIMAL - only 3kb minified and zipped.

NANNY STATE stores everything about the app in a single state object and automatically re-renders the view when the state changes. This means that your code is more organized and easier to maintain without the bloat of other libraries. And everything is written in vanilla JS and HTML, which means you don't have to learn any new syntax!

It's easy to get started - just follow the examples below and you'll see some impressive results in just a few lines of code.

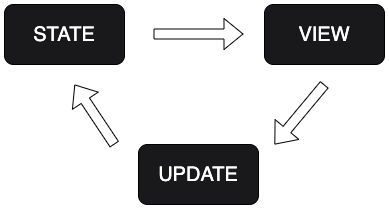

NANNY STATE uses a one-way data flow model comprised of 3 interdependent parts:

- State - an object or value that stores all the app data

- View - a function that returns a string of HTML based on the current state

- Update - a function that is the only way to change the state and re-render the view

In NANNY STATE, the state is everything. It is the single source of truth in the application and it can only be changed using the Update function, ensuring that any changes are deterministic with predictable outcomes. The view is an HTML representation of the data stored in the state. When a user interacts with the page, the Update function changes the state and the view is automatically re-rendered to reflect these changes.

NANNY STATE was inspired by Hyperapp and Redux and uses the µhtml library for rendering. It is open source software; please feel free to help out or contribute.

The name is inspired by the British phrase for an overly protective, centralised government. In a similar way, NANNY STATE protects all the app data by storing it centrally.

Install nanny-state from NPM.

npm install nanny-stateThen import like this:

import { Nanny, html } from "nanny-state"If you use ES Modules, you don't need NPM. You can import from a CDN URL in your browser or on CodePen.

<script type="module">

import { Nanny,html } from 'https://cdn.skypack.dev/nanny-state'

</script>Building a NANNY STATE app is simple and straightforward. It always follows these steps:

-

Import the

Nannyandhtmlfunctions:import { Nanny, html } from 'nanny-state'

-

Create the

Viewtemplate - a pure function that accepts the state as its only parameter and outputs a string of HTML:const View = state => html`<h1>Hello ${state.name} <button onclick=${state.changeName}>Click Me</button>`

-

Create an event handler to call the

Updatefunction and update the state:

const changeName = event => Update({ name: "Nanny State" })- Create the initial

Stateobject (everything goes in the State, props, the View and event handlers):const State = { name: "World", changeName, View } ```

- Assign the

Updatefunction to the return value ofNanny(State):

const Update = Nanny(State)The easiest way to learn how NANNY STATE works is to try coding some examples. All the examples below can be coded on CodePen by simply entering the code in the 'JS' section.

Alternatively you could set up a basic HTML file and place all the code inside the <script> tags. You can see example files here.

And if you want it to look pretty, just copy the CSS code from the examples on CodePen!

This example will show how the 3 elements of Nanny State, State, View and the Update function, work.

Start by importing the relevant functions:

import { Nanny, html } from 'nanny-state'Next we'll create the view. This is a function that accepts the state as an argument and returns a string of HTML that depends on the value of the state's properties.

const View = state => html`<h1>Hello World</h1>`Views in NANNY STATE use the html template function that is part of µhtml. This is a tag function that accepts a template literal as an argument. The template literal contains the HTML code that we want to display in our app.

These values are then bound to the view and will automatically update to reflect any changes in the state. In this example we are inserting the value of the state object's 'name' property into the <h1> element.

In NANNY STATE, everything is stored as a property of the state, even the app settings such as the view! This means that we have to add the View code to the State object. Since we named the variable View, we can just use object-shortand notation to add this to the State object, like so:

const State = {

View

}Last of all, we need to call the Nanny function with State provided as an argument:

Nanny(State)This passes the State object into the Nanny function, which renders the view based on the initial state.

You can this code on CodePen.

This is just a static piece of HTML though. The view in Nanny State can display dynamic expressions using ${expression} placeholders to insert properties from the state.

Let's add a property called 'name', with a value of the string "World", to the state:

State = {

name: "World",

View

}Now let's update the View to use this property:

const View = state => html`<h1>Hello ${state.name}</h1>`Even though, outwardly, nothing seems to have changed, we are now using properties of the State in the View.

You can this code on CodePen.

Our next job is to make the view dynamic. First of all we'll add a button to the view:

const View = state =>

html`<h1>Hello ${state.name}</h1>

<button onclick=${state.changeName}>Hello</button>`The button element has an inline event listener. When the button is clicked the event handler changeName will be called (by convention, event handlers start with an _ to differentiate them from other properties in the State). We want this function to update the state object so the 'name' property changes to 'Nanny State'. This is exactly what the Update function is for.

The Update function is returned when the Nanny function is called. Calling the Nanny function does 2 things:

- Renders the initial view based on the initial value of the

Statevariable that is passed to it. - Returns the

Updatefunction - this is the only way that the state can be updated in the app.

To create the Update function, change the last line of code so it assigns the variable Update to the return value of Nanny(State):

const Update = Nanny(State)Note that it is only called Update by convention and can actually be called any legal variable name.

Now we can use the Update function to update the state when the button is clicked. This is really easy to do - simply pass an object representing the new state as an argument to the Update function.

To do this we need to add the changeName event handler to the State:

const State = {

name: "World",

changeName: event => Update({name: "Nanny State"}),

View

} Because changeName is an event handler, its only parameter is the event object (although it isn't actually needed in this example, but it is useful to identify the function as an event handler). In this case, the purpose of the function is to call the Update function that changes the 'name' property to "Nanny State" by passing the object {name: "Nanny State"} as an argument to the Update function. Note that you ony have to include any properties of the State that need updating in this object(Nanny State assumes that all the other properties will stay the same). NANNY STATE will then automatically re-render the view using µhtml, which only updates the parts of the view that have actually changed. This means that re-rendering after a state update is fast and efficient.

We now have everything wired up correctly. When the user clicks the button, the changeName event handler is called. This calls the Update function which changes the 'name' property to 'Nanny State' and re-renders the page based on this new state.

You can this code on CodePen. Try clicking the button to see the view change!

Now let's try adding an event handler that uses some information passed to it in the event object. We'll create an input field that allows the user to update the name property as they type. Change the view to the following:

const View = state => html`<h1>Hello ${state.name}</h1>

<input oninput=${state.changeName}>`We've replaced the button element with an input field that uses the inline event listener oninput to call the changeName event handler. We need to update this function inside the State object:

const State = {

name: "World",

changeName: event => Update({name: event.target.value}),

View

} This time the Update function is passed an object that replaces the name property of the state with the value of event.target.value which corresponds to the text entered into the input field. Every time the input changes, this event will fire and the view will be re-rendered to correspond to what has been typed into the input field.

You can this code on CodePen. Try typing into the input field and see the view change as you type!

This next example shows how to implement a toggle function as well as how to render parts of the view based on the value of properties in the State.

Start, in the usual way, by importing the relevant functions:

import { Nanny, html } from 'nanny-state'Next we'll create the view:

const View = state => html`<h1>${state.salutation} World</h1>

<button onclick=${state.changeSalutation}>${state.salutation === "Hello" ? "Goodbye" : "Hello"}</button>`This view displays a property of the State called salutation followed by the string "World" inside <h1> tags. The value of State.salutation will either be "Hello" or "Goodbye". After this is a button element with an onclick event handler attached to it that calles the changeSalutation State method. Inside the button we use a ternary operator to display "Goodbye" if the salutation is currenlty "Hello" or display "Hello" otherwise. We want the value of State.salutation to toggle between "Hello" and "Goodbye" when this button is clicked.

Let's create the initial State and implement the changeSalutation method:

const State = {

salutation: "Hello",

changeSalutation: event =>

Update(state => ({salutation: state.salutation === "Hello" ? "Goodbye" : "Hello"})),

View

}As you can see, the salutation property is set to "Hello" initially and the View function is added to the State as usual. Let's take a closer look at the changeSalutation method. In the previous examples, the Update function was passed a new representation of the state, but in this example it is passed a transformer function. These are particularly useful when the new state is based on the previous state, as in this case.

A transformer function accepts the current state as an argument and returns a new representation of the state. They are basically a mapping function from the current state to a new state as shown in the diagram below:

ES6 arrow functions are perfect for transformer functions as they visually show the mapping of the current state to a new representation of the state.

Transformer functions must be pure functions. They should always return the same value given the same arguments and should not cause any side-effects. They take the following structure:

state => newStateIn the changeSalutation example above,the transformer functions checks the value of the state.salutation property and then toggles the value accordingly, so if the value is "Hello" it updates it to "Goodbye" and vice-versa:

state => ({salutation: state.salutation === "Hello" ? "Goodbye" : "Hello"})Transformer functions are passed by reference to the Update function. The current state is implicityly passed as an argument to any transformer function (similiar to the way the event object is implicitly passed to event handlers when they are called).

All we we need to do now is start everything running and define the Update function:

Nanny(State)You can this code on CodePen. Click on the button to toggle the heading and button content!

Every state managememnt library needs a counter example!

We start in the usual way by importing the necessary functions:

import { Nanny, html } from 'nanny-state';Now let's create the view that will return the HTML we want to display:

const View = state => html`<button onclick=${state.incrementCount}>${state.count}</button>`This is a button that displays the number of times the button has been clicked on, which is a property of the State called count. It also has an onclick event listener attached that is a method of the State called incrementCount. This will be responsible for increasing the value of the count property by 1 every time the button is pressed.

Now we need to define the State object:

const State = {

count: 0,

incrementCount: event => Update(state => ({count: state.count + 1})),

View

}This sets the initial value of the count property to 0 and defines the incrementCount method. It calls the Update function and passes a transformer function that sets the new value of count to the current value of state.count with 1 added on.

Transformer functions don't need to return an object that represents every property of the new state. They only need to return an object that contains the properties that have actually changed. For example, if the initial state is represented by the following object:

const State = {

name: "World",

count: 10

}If we write a transformer function that doubles the count, then we only need to return an object that shows the new value of the 'count' property and don't need to worry about the 'name' property:

state => ({ count: state.count * 2})Note: when arrow functions return an object literal, it needs wrapping in parentheses

The state object in the parameter can also be destructured so that it only references properties required by the transformer function:

{ count } => ({ count: count * 2})As usual, the State object also requires View to be added as well.

Last of all, we just need to call the Nanny function and assign its return value to the variable Update:

const Update = Nanny(State)This will render the initial view with the count set to 0 and allow you to increase the count by clicking on the button.

You can this code on CodePen. Click on the button to increase the count!

If you want an event handler to have parameters in addition to the event, then this can be done using a 'double-arrow' function and partial application. The additional arguments always come first and the event should be the last parameter provided to the function:

const handler = params = event => newStateNote that this is a standard Vanilla JS technique and not unique to Nanny State

For example, if we wanted our counter app to have buttons that increased the count by 1, 2 or even decreased it by 1, then instead of writing a separate event handler for each button, we could write a function that accepted an extra parameter of how much to increase the value of state.count by. We could rewerite incrementCount like so:

incrementCount: (n=1) => event =>

Update(state => ({count: state.count + n}))Here the parameter n is used to determine how much state.count is increased by and has a default value of 1. This makes the event handler much more flexible.

When calling an event handler with parameters in the View, it needs to be partially applied with any arguments that are required. For example, this is how the View would now look with our extra buttons:

const View = state => html`

<h1>${state.count}</h1>

<div>

<button onclick=${state.incrementCount()}>+1</button>

<button onclick=${state.incrementCount(2)}>+2</button>

<button onclick=${state.incrementCount(-1)}>-1</button>

</div>`Notice that the state.incrementCount function is actually called in the view with the first parameter provided (or if no parameter is provided the default value of 1 will be used. The event object will still be implicityly passed to the event handler (even though it isn't used in this example).

You can see the code for this updated counter example on CodePen. Click on the buttons to increase or decrease the count by different amounts!

Because NANNY STATE just uses vanilla JS, you can define anonymous event handlers directly inside the View. For example, the counter example above could have been written with the following view instead:

const View = state => html`

<button onclick=${e => Update(state => ({count: state.count + 1}))}>

I've been pressed ${state.count} time${state.count === 1 ? "" : "s"}

</button>`This uses the following anonymous event handler:

e => Update(state => ({count: state.count + 1}))This saves the event handler having to be defined in the State object, which can be useful for small updates such as this, although it could get unweildy for more complicated updates.

One advantage of using anonymous event handlers directly in the view is that they can access the state because the View function accepts the current state as an argument, whereas event handlers that are defined in the State object do not have access to the state.

You can see a full set of examples of how Nanny State can be used, with source code, on CodePen. This includes:

-

Numble - A numerical Wordle clone (by Olivia Gibson)

-

Times Tables Quiz (by Olivia Gibson)

Now that you've learnt the basics of NANNY STATE, here's some extra info that helps give you some extra control over the settings.

The Initiate function is a method of the state object that is called once before the initial render. It has access to the state and works in the same way as the Update function in that its return value updates the state.

For example, adding the following method to the State object in the counter example will set the start value of the count property to 42:

Initiate: state => ({count: 42})Of course this could have just been hard coded into the State object directly, but sometimes it's useful to programatically set the initial state using a funciton when the app is initialized.

The Before and After functions are methods of the state object that are called before or after a state update respectively. They have access to the state and work in the same way as the Update function in that their return value update the state.

For example, try adding the following methods to the State object in the 'Hello Nanny State' example to the following:

Before: state => console.log('Before:', state.name)

After: state => console.log('After:', state.name)Now, when you press the Hello button, the following is logged to the console, showing how the state has changed:

"Before:"

{

"name": "World"

}

"After:"

{

"name": "Nanny State"

}

By Default the view will be rendered inside the body element of the page. This can be changed using the Element property of the state object or by providing it as part of the options object of the Nanny function. For example, if you wanted the view to be rendered inside an element with the id of 'app', you just need to specify this as an option when you call the Nanny function:

State.Element = document.getElementById('app')Debug is a property of the state that is false by default, but if you set it to true, then the value of the state will be logged to the console after the initial render and after any state update"

State.Debug = trueLocalStorageKey is a property of the state that ensures that the state is automatically persisted using the browser's local storage API. It will also retrieve the state from the user's local storage every time they visit the site, ensuring persitance of the state between sessions. To use it, simply set this property to the string value that you want to be used as the local storage key. For example, the following setting will use the string "nanny" as the local storage key and ensure that the state is saved to local storage after every update:

State.LocalStorageKey = 'nanny'Routing is baked in to NANNY STATE. Remember that the State Is Everything, so all the routes are set up in the State object. Simply define a property called Routes as an array of route objects. Route objects contain the following properties:

path: the path used to access the routetitle: the title property of the routeview: a function that works exactly like the mainViewfunction (a bit like a sub-view) and accepts the current state as an argument and returns a string of HTML

Here's a basic example:

Routes: [

{ path: "/", title: "Home", view: state => html`<h1>Home</h1>` },

{ path: "about", title: "About", view: state => html`<h1>About Us</h1>` },

{ path: "contact", title: "Contact", view: state => html`<h1>Contact Us</h1>` }

]Let's use those route objects to build a mini single-page website.

First of all we need to create the main View. When using routes, this takes the form of a template layout for all pages and we use the special Content property of the State to indicate where the specific content from each route will be displayed in the layout. Here's a basic example:

const View = state => html` <h1>Nanny State</h1>

<h2>Router</h2>

<nav>

<ul>

<li><a href="/" onclick=${state.Route()}>Home</a></li>

<li><a href="/about" onclick=${state.Route()}>About</a></li>

<li><a href="/contact" onclick=${state.Route()}>Contact</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

<main>${state.Content}</main>`The first thing to notice here are the state.Content property inside the <main> tags. This will render a different view, depending on the route. This is the function that is provided as the view property in the route object.

The other thing to notice is the built-in state.Route() method. This will update the current route to the argument provided. If no argument is provided then it will automatically use the value of the href attribute. So, in the example above, clicking on the 'About' link will update the route to '/about'.

Now we just need to create the initial State object. This needs to contain the Routes array that contains a route object for each route as well as the View:

const State = {

Routes: [

{ path: "/", title: "Home", view: state => html`<h1>Home</h1>` },

{ path: "about", title: "About", view: state => html`<h1>About Us</h1>` },

{ path: "contact", title: "Contact", view: state => html`<h1>Contact Us</h1>` }

],

View

} Last of all we just need to start the Nanny State:

Nanny(State)Note that in the is example we didn't need the Update function

You can see this example on CodeSandbox (note that routing won't work on CodePen).

You can create nested routes by adding a routes property to a route object. This is an array that acts in the same way as the top-level Routes property and contains nested route objects.

For example, if you wanted the route '/about/us' to go to display the About page, you could update the Routes array above to the following:

Routes: [

{ path: "/", title: "Home", view: state => html`<h1>Home</h1>` },

{ path: "about", routes: [ { path: "us", title: "About Us", view: state => html`<h1>About Us</h1>` }] },

{ path: "contact", title: "Contact", view: state => html`<h1>Contact Us</h1>` }

]The routes array in any route object can contain as many nested routes as required.

The : symbol can be used to denote a wildcard route. For example, the following route object using a wildcard called :id in its path property:

{ path: ":name", title: "Programming Languages", view: state => html`<h1>${state.language)</h1>` }When the user visits the URL path '/javascript' a params object will be created with the a key of "name" and value of "javascript". This can then be used in an update function that can be added to the route object and works in exactly the same way as the NANNY STATE Update function, it accepts the current state and returns a new state. The different is that this also accepts the params object as its first parameter (this is passed automatically to the update function along with the state.

In this example we could add the following update function to the route object:

{ path: ":name", title: "Programming Languages", view: state => html`<h1>${state.language)</h1>`, update: params => state => ({ language: params.name}) }This will set the language property of the state to be the same as the name property of the params object, in other words it will be set to whatever was entered into the URL. This property is then displayed as a heading in the view for this route.