-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 682

New issue

Have a question about this project? Sign up for a free GitHub account to open an issue and contact its maintainers and the community.

By clicking “Sign up for GitHub”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy statement. We’ll occasionally send you account related emails.

Already on GitHub? Sign in to your account

[css-fonts] Font Sizing for Readability #6709

Comments

|

Also see #731 #6371 etc. There have been changes to Also, ex height is really only meaningful for Euroscript (Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, somewhat for Armenian and Georgian), which of course collects a lot of landowners and wollen text out there. PS 2024: I just read my comment from three years ago and couldn’t tell what the last clause (“landowners and wollen”) was meant to say before autocorrect mangling. |

|

Hi Christoph @Crissov

I reviewed them, but it's really not an intuitive way to set a font size, and does not solve the problem from an accessibility guidelines perspective. What is needed is to be able to set the font size at a specific x-height directly, i.e. as the examples I provided above. This has been a project over here since 2019, associated with the visual contrast work that is part of WCAG 3. There is probably still a place for At the moment the only implementation is Firefox, all other browsers have dropped support for it. Using the Firefox implementation there are unexpected behaviors such as with line-height and em units, which I discuss above and on the samples page. But even is some of those are fixes, it is not an intuitive way to define a font height for a standard — it's confusing and cumbersome. I saw your post regarding a font-size for the @font-face, and I was working on something similar, as yes that is needed too. And where these are leading:In addition to needing to set a specified size for accessibility guidelines, there are needs regarding text zoom and reflow. I'm getting ahead of myself here, but what is needed for text zoom is on this page: https://www.myndex.com/WEB/TextZoomExample What is needed is not a zoom by percentage, but to a specific text size, where the smallest text is zoomed up to the needed size, but larger text on the page is zoomed only enough to maintain a position as "larger" even if larger by only 1 px. And the starting and ultimate size is defined in px, not as a percentage. And that px needs to relate directly to x-height. Just an example — there are a lot of other properties needed to help define meaningful standards and guidelines for readability, but many of them rest on this basic one of setting x-height with a length, either absolute (px) or relative (em). Also the name, Instead of

That's sort of like saying "it only applies to people with computers"... And ultimately not entirely true, as many alphabets are structured with glyphs at different sizes. — I believe this is going to be important for Korean fonts for instance. BUT that's not the actual point.Here is the point: A font has a body size, usually large enough to contain all the glyphs and ascenders and descenders, and perhaps swashy embellishments etc. Setting the font size does not relate directly to the glyph size in a standard way (as I've shown). This is true in other scripts even if it does not have upper/lower case. What is important for readability guidelines is to be able to specify how big a glyph is rendered to the screen, not the font body size which contains whatever amount of empty space. There is no standard for glyph size nor weight, nor anything else, really. These values vary not only per foundry, but even in the same foundry with different families. As a result, creating a guideline that "minimum font size..." is literally meaningless — unless it is directed at something that can be measured and results in a (somewhat) consistent size rendered to screen. For latin scripts, we know that the critical size for fluent readability at 20/20 is an x-height of 9.4px. That might be possible with a 16px font size using Verdana, or you might need an 18.8px size... for Times New Roman you need the font size at 21px to achieve that critical size. Thank you, Andy |

A TL;DR Summary:

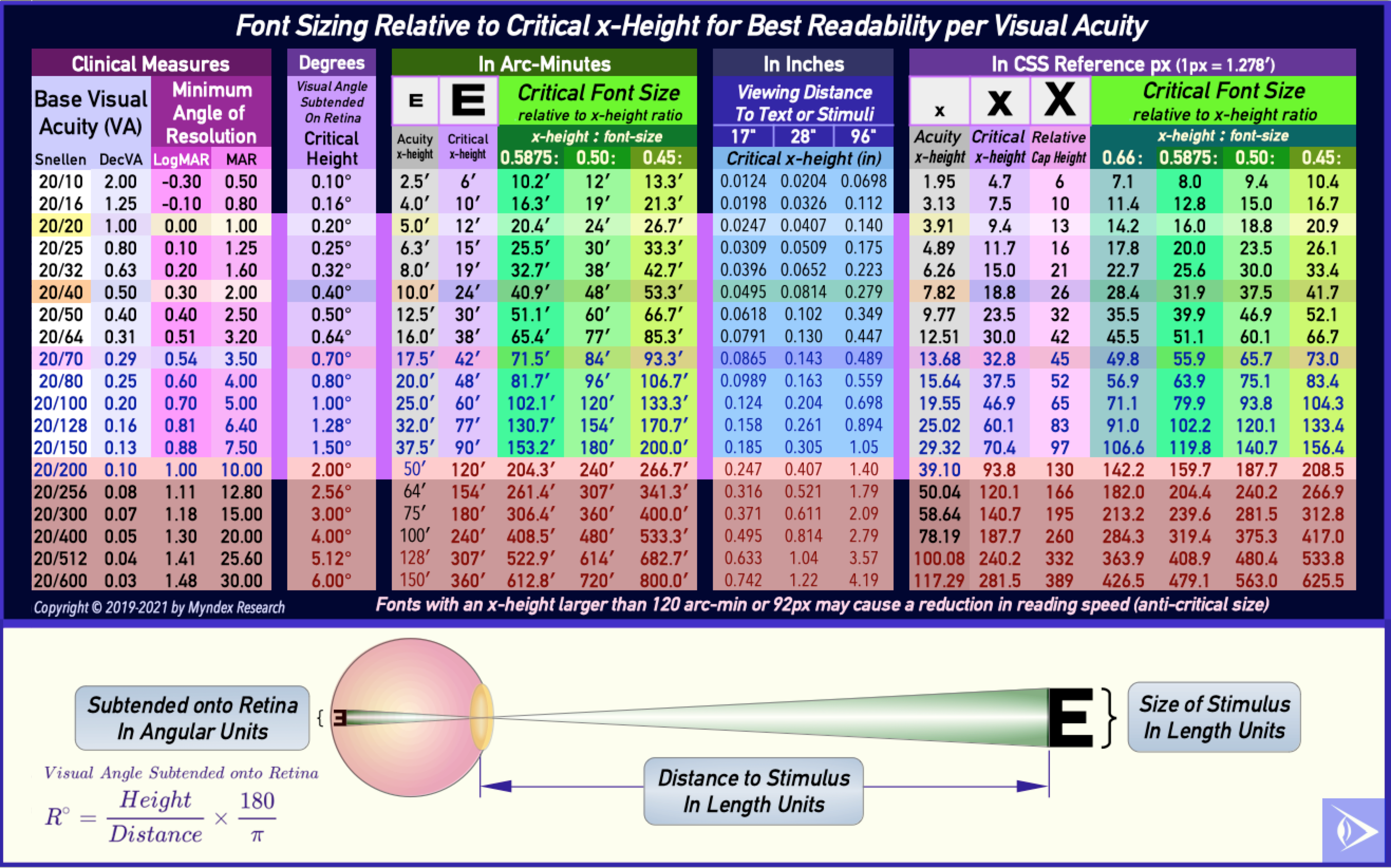

Other critical metrics for readability are font weight, leading (line-height), tracking (letter-spacing), and kerning. There is no effective standard how size nor any of these result in a particular family rendering to screen. These are among the most critical accessibility failures facing web content today. Thank you, Andy PS: Here's a chart that outlines critical reading size, based on visual angle, which references the research of Dr. Lovie-Kitchin on critical size for readability. As a statistical reference, only about 45% of the population is at or better than 20/20. "Impairments begin at 20/20" you might say. The average and median acuity is about 20/40 (which is the limit in all 50 states for a non-commercial drivers license). "Low vision" is 20/70 and worse, and "blind" is 20/200 and worse. |

|

Thoughts on having a mode switch like p {

font-sizing: ex;

font-size: 1.2ex;

}would be equivalent to p {

font-size: 1.2em;

}All the units would be the same. This would only change the behavior of Like Some more possible things to explore: This could also incorporate what @fantasai has done with the |

|

Hi Scott @scottkellum

I like this the more I think about it, actually makes a lot of sense to make it a switch like this. We pretty much never used x-height in traditional print.... We need set size with x-height now because the web is not fixed in place like print, it's always dynamic and always changing. My concern is the amount of breakage this can do, at least until the property is widely adopted. How would it fallback for browsers the don't support it...? A reason I was suggesting the property as above is that fallback would be easy: div {

font-size: 21px;

font-x-size: 12px;

}This assumes of course that

div {

font-sizing: ex;

font-size: 12px;

border-width: 1em;

}In this case what would the border width be? 12px, 17px, 23px, or 24px? What if

|

This is why I think it shouldn’t be inherited like Additionally div {

font-size: 16px;

}

@supports (font-sizing: ex) {

div {

font-sizing: ex;

font-size: 12px;

}

}

In your example: div {

font-sizing: ex;

font-size: 12px;

border-width: 1em;

}It depends on the font used, but assuming a ratio of

As it is so rare that a font provides the ability to adjust the x-height, I think this might be out of scope for this spec. When that adjustment is available, the variable font axis is unregistered. If a font author wants the x-height to be adjustable, they can do that now by letting people set it with CSS like Additionally, the variability of x-height is part of the point of having a feature like this in my view. Currently the only way to do this is create a table and do this with a tool like the web font loader. Allowing font sizing via x-height is a tool to work with this variability instead of lock it to a specific ratio. Here is an excellent video on the need for font-sizing by x-height from @chrisarmstrong. |

|

I've always wanted to be able to specify the size of x-heights and cap-heights in CSS without having to know a font's internal font metrics ahead of time. This desire has only become stronger now after being able to do something like that in newer versions of Adobe Illustrator (which also offers the "ICF box" as a font-sizing option for East Asian CJK typography). The new-ish As such, I've always longed for something like Something like Scott's proposed property would be even more powerful if it could be more than just a numberless unit. For example, instead of Either way, I don't think the ideas of simple properties like |

|

One clarification that would have to be made with something like I tend to lean toward the latter because |

|

@nicksherman My opinion on the relationship between font size and 1em:

I’m trying to think of ways to not mess up relative font units when doing this and I think |

|

Hi Nick! @nicksherman Glad to see there is still interest here—this conversation has obviously been continuing for years...

Me too. Among other things, creating design guidelines that are consistent is challenging when the technology itself is completely inconsistent! The way things work, the browser developers need to incorporate the features into their browsers before it will do us any good. ex-to-em

In my first post at the top, I did—I call it It's Not Just for ConvenienceUser personalization is the holy grail of accessible interactive design. But you can not have good personalization unless you have technology that is perceptually uniform, and provides predictable results, able to accommodate any given person's user needs. This Means:

The Buck Stops a Bunch of PlacesRight now, web standards like WCAG are relying on the author and content creator—but many of the user needs are really only achievable when incorporated into the technology (i.e. the user agent or browser). Arguably, WCAG should not be relying on content authors to effectuate all of the accessible accommodations needed. Years ago when W3C WAI attempted to develop standards for browsers & the technology, developers were less than enthusiastic The politics of international standards can be.... eh.... nefarious. As a result, WAI created WCAG, saddling content creators with some tasks that would be better served by mature technology. Some Stuff Have We, Yes?Progress is being made, but we are a long way from the ideal of automated and robust personalization-on-demand for all. Some things that would be very helpful is supported or better supported by the technology:

And all these features help to enable better text reflow and responsive design, so users can adjust to their needed text size without breaking the layout. Thank You, Andy Andrew Somers |

|

Have you considered the If you set For example: Without |

|

Hi @jfkthame Yes, and wrote about it in my posts above.

It really does not work in a way that’s useful IMO. And moreover it’s not supported in a useable way. It is not the answer. I have some links above to demo pages, which present some of the fundamental issues we’re discussing. And if we are going to push browser developers to incorporate something like this, let’s incorporate it in a way that’s easy for designers, requires no math, and is intuitive. “ |

|

While Rereading your posts (apologies, skimming your original post; it's quite long), I don't immediately see a meaningful difference between

(Instead allowing the |

|

What appeals to me about this proposal over font-size-adjust is that you don't have to know about the metrics of a font to normalize their appearance. Setting font size by x-height directly is not just more straightforward, but also works more consistently for more complex font stacks and fallbacks. I do have disagreements with this proposal. Font-x-size and font-cap-size along with the font-size property seem to imply these metrics can be controlled individually. The ex-to-em property is more explicit about this font proportion adjustment. My understanding of this means new font tech would need to be created, standardized and widely adopted to reliably implement this. This is why I proposed a toggle that changes what metric font-size uses in thread. To wrap up, a way for authors to explicitly say what the x-height size of text is would be useful. Edit: I do think |

|

Hi @tabatkins thanks for the comment, my reply:

I would usually disagree, simply from the standpoint that it's been bashed around for years without being adopted. Though I do see that last year Safari added it, so maybe there's hope for it after all.

A bit of a strawman argument, especially if the lack of adoption is because it's difficult to implement, or causes unexpected problems, or is confusing to use.

That was the premise of my first post here.

But they don't. One sets character height by

Designers have expressed to me directly that "no math" is best. If you're a developer, that nuance may not seem relevant. In my first two posts here, I laid out the reasons I found at the time that it is relevant. Some perhaps can be fixed within FSA. Was just looking at the example page from a while ago testing

'font-size-adjust: cap-height 0.73;' doesn't work on Safari, not yet anyway.

If they both win, that means independent control of the upper case and lower case glyphs. Then, perhaps that indicates a But again, these are straw arguments, because it makes no difference if you have: /* With Fallbacks — unsupported browsers fallback to font-size*/

p {

font-size: 16px;

font-x-size: 9.4px;

font-cap-size: 11.5px;

}

VERSUS /* With Fallbacks — unsupported browsers fallback to font-size*/

p {

font-size: 16px;

font-size-adjust: 0.52;

font-size-adjust: cap-height: 0.715;

}

The difference between these two scenarios is that

I like this better than A key advantage of setting the x-height directly relates to guidelines and testing against standards. Setting directly eliminates ambiguity. Using

Advantage: You can put Disadvantage: Putting

article {

font-size: 16px;

font-size-adjust: 0.52;

}Everything inside that article will get that x-height. But what if: blockquote {

font-size: 21px;

font-family: TrajanPro;

}And the HTML is: <article>

<p>Lorem ipsum get sum dim sum</p>

<blockquote>...Why do I suddenly crave chinese food?</blockquote>

<p>Lorem ipsum get sum dim sum is calling you</p>

</article>Trajan Pro is an all uppercase font, and it's probably going to render much smaller than expected or desired here, as the blockquote inherits the

Last comment

|

|

Hi Scott @scottkellum

They could be controlled independently in theory — size, weight, and baseline shift are three parameters that come to mind that are useful to be independent for upper and lowercase.

Well, on the browsers that have it, If you go to this sample page using Firefox or current Safari, it's apparent that more is needed... |

|

To solve the issue of PS: Nevermind, I just realized after hitting submit that I already mentioned #731 before. |

Features Needed for Better Readability

Part I: Font Sizing (x-height)

I'm a member of the W3 AGWG, the Low Vision Task Force, the Silver Task force, and the author of WCAG 3 Visual Contrast and the APCA contrast tool. My objective is making the web easier to read for all sighted users. The following proposed CSS properties support this goal. I'm going to list proposed additions first as briefly as possible, and then the supporting commentary afterwards.

Problems These Will Solve:

Emerging standards regarding visual readability in WCAG 3 put a much greater emphasis on font size and weight. But neither size nor weight are standardized in terms of how a given font actually renders onscreen. There is no standard relationship of a font's size of body/x/cap.

Accessibility standards need to specify letter sizes in a way that is consistent and testable, particularly specifying the size lower-case letters appear on the screen. (See discussion below for why this is different than

font-size-adjust).This post covers only x-height related size. Width, zoom, aspect ratio, weight, etc. will be covered in other issue posts.

Proposal for a direct x-height property:

font-x-size:So that accessibility and readability standards can specify meaningful size guidelines, we need a CSS property that can set a font's size by directly specifying the desired x-height. And there are some related properties needed to support that in a stable and functional way.

font-x-size:would take an absolute or relative length, and/or inherit and otherwise work very much like the presentfont-size:, except thatfont-x-size:would directly set the x-height of the current element.Examples

div { font-x-size: 12px; }// Set the font’s x-height to 12px, (more or less a font-size of 24px, depending on ratio).div { font-x-size: 1em; }// Set the font’s x-height to the font body height of the parent element's font.div { font-x-size: 1ex; }// Set the current font’s x-height to match the parent element’s x-height. This would also be the behavior of theinheritkeyword.Ideally associated with this, there would also be a

font-cap-size:to directly set uppercase size, and related properties for certain other languages (such as Korean) that have use for a more granular approach to size.Companion Property

Because x-height vs font body height is not consistent, if font size is being set via font-x-size, then the em value needs to be defined relative to the x-height, or else inherited relative values downstream can have unexpected results (a problem with

font-size-adjust).Therefore, when font-x-size is used to set the font size, then the em value for that element should default to 2 times the x-height as set. This will cascade to key properties like

emandline-height. But 2x may not always be best, so for flexibility an additional property isex-to-em:When

font-x-size:is used, theex-to-em:property will set the em size as 2x the x-height as default, but when added will allow fine-grained control of the em value for that element.More Examples

Here, ex-to-em is using a unitless measure, so the em is set to 18px. This is the same as an x-height ratio of 0.667.

Here, ex-to-em is using a unitless measure less than 1, so the em is set to 18px, exactly as above. This is allowed because the while em can be set equal to the x-height (with 1.0) em will never be set to less, therefore values over 1.0 set the em as a multiple of the x-height, and under 1.0 the em is set as the reciprocal of the ratio.

Here, ex-to-em accepts a length, so is used to assert that 1em = 20px in the current scope, without otherwise affecting the current font (but it does affect em related properties like line-height). This would be a good tag to have for use in other contexts as well.

Here, em defaults to 24px because font-x-size is used to set the font size to 12px.

Legacy user agents that don't support font-x-size are given a font-size earlier, with font-x-size over-riding. The most recent or most specific font-size or font-x-size will be determinant, allowing one or the other to be placed in media queries, or inline, as needed.

This would hold true for font-cap-size as well, for fine control if for instance a font needed to be used in all-caps for a button or headline to give fine and accurate control of the upper case size.

DISCUSSION

For a brief background, in April 2019 I raised some issues regarding WCAG 2 and the contrast methods used therein. As a result of those discussions I became a member of the W3 AGWG to help solve some of these issues. For the last few years I've been immersed in research into vision, contrast, readability, aiming to solve these and related issues for web content.

I looked into

font-size-adjust:some time ago, when it had more support than it does now. At one point it was marked as depreciated, and today it is supported only on Firefox. Unfortunately, its use is counter intuitive and/or has unexpected results but moreover, it does not support the developing standards and guidelines.This is not about fallbacks, this is about an affirmative way to define a size on screen for a font. Ideally accessibility guideline for something such as a font size is both concrete and easy to implement, otherwise it gets ignored. If the guideline says "body text shall be no smaller than an x-height of 9.4px" the content creator needs to be able to set

font-x-size:9.4px;and be done.Also the present implementation breaks or causes unusual behavior in other important properties such as line-height. Since this property does not set the font size directly some calculations and/or a JS polyfill are needed for a practical solution. And that's a problem, because if it isn't widely supported, and also easy to implement, we can't really make it a useful or normative part of a guideline.

Background on Font Sizing

Spatial Frequency is a primary determiner of perceived contrast, and by extension readability. In a practical sense, spatial frequency most relates to font weight & stroke width (border width), but also font size, and tracking/kerning/leading (letter and line spacing). While developing the SAPC and APCA algorithm for Silver, investigation revealed scientific consensus that spatial frequency, and not color, is the more critical factor when it comes to perception of contrast at high spatial frequencies (small and thin fonts). This has substantial implications for critical font size and weight, as well as critical color distances and contrast.

The Font Problem: in the early 80s, before personal computers and WYSIWYG desktop publishing, and before I was in the film industry, I did newspaper pasteup the old fashion way: sending things to a typesetter, getting it back a day later and using razor blades and hot wax to pastup. The ink was black _only_, never grey, so to modulate contrast we’d use a lighter or heavier weight font. Today, it takes nothing to flick the CSS color codes into some truly bad design choices.

But wait, there’s more: this problem has accelerated since 2008 and WCAG 2.0. Back then, everyone used ”core web safe” fonts, because it was problematic and unreliable to do it any other way. Websafe fonts and "core" fonts were mostly a decent weight to render well onscreen like Verdana (a notable exception is the atrocious Courier New a far too thin copy of the classic Courier.) Also a decade ago, web designers commonly used black text on a light background. And in truth, that was art school and classical design way back when: Strong contrast, especially for body text.

Yet even so, here are two common, core fonts, Verdana and Times New Roman. And both are set at the same 14px:

Fast forward to our modern era and web publishing is in the hands of anyone with the inclination. No need to know what an offset press is, or know why it was best to use only black ink for body text, modulating contrast with only font weight instead.

And Then…. Google FONTS. Google fonts made font access easy for all web sites, hosting a thousand free fonts in all weights including too thin to see when small including for normally sighted individuals. And some sites are using these thin fonts AND using them with light grey or other low contrast all at the same time. Combine this with things like webkit-smoothing, and boom, too much of the internet is unreadable for too many now.

SIDE NOTE: A contributing factor is that some have developed the idea the WCAG AA ”4.5:1” is a valid target for all text in all contexts, when nothing could be farther from the truth. 4.5:1 as a color contrast might be more than enough in some cases, or it could be appallingly insufficient. In example it is very insufficient for small thin fonts especially used for body text, where 10:1 is more appropriate.

Font Inconsistency: There are few real standards for fonts: there is no standard for instance that specifies the ratio of the x-height to the font-size. As a result, it is difficult to predict how content will appear on some browsers. Fonts are literally all over the place in terms of their x-height. Take a look at this font evaluation for plenty of examples of inconsistent x-height.

If we are authoring standards, we need a consistent and repeatable way to determine things such as how big a font renders on the screen. Defining the standard around x-height makes the most sense, as the vast majority of text is composed of the lower case letters. If we could affirmatively set the font's rendering size based on x-height, we could set a consistent size regardless of variations in font design (whimsy fonts notwithstanding).

In support of this, I have a demonstration page of the need for a better font-size method. In it you'll see that in the first test panel there is a small sampling of fonts, and they are all set at

font-size: 24px;, but the x-height varies from 6.7px to 13.44px. That is literally a two fold difference. Or put another way, it's the difference between 20/20 and 20/40 vision.So to promote effective accessibility standards, we need these font size properties. And this is one of the areas of accessibility where it is clear that everyone will benefit.

Thank you,

Andy

Andrew Somers

W3 AGWG Invited Expert

LVTF/Silver Task Force

Myndex Color Science Researcher

Inventor of the APCA & SAPC

APCA — THE REVOLUTION WILL BE READABLE™

The text was updated successfully, but these errors were encountered: