(Review by David Ha)

Images used in this summary was taken from blog.otoro.net and used with permission from the author.

Generating Sequences With Recurrent Neural Networks, written by Alex Graves in 2013, is one of the fundamental papers that talks about sequence generation with recurrent neural networks (RNN). It discusses issues modeling the probability distribution of sequential data. Rather than having a model predict exactly what will happen in the future, the approach is to have the RNN predict the probability distribution of the future given all the information it knows from the past. Even for humans, it is easier to forecast how likely certain events will be in the future compared to predicting the future exactly.

However, this is still a difficult problem for machines, especially for non-Markovian sequences. The problem can be defined as computing the probability distribution of the sequence at the next time step, given the entire history of the sequence.

[//]: # (

P( Y[n+1]=y[n+1] | Y[n]=y[n], Y[n-1]=y[n-1], Y[n-2]=y[n-2], ... ) (1)

Simple methods, such as the N-gram model, predict the next character of a sentence given the previous N characters. They approximate (1) by truncating before time n-N. This doesn’t scale well when N grows.

In this paper, Graves describes how to use an RNN to approximate the probability distribution function (PDF) from (1). Because RNNs are recursive, they can remember a rich representation of the past. The paper proposes using LSTM cells in order to have the RNN remember information even in the distant past. With that change, the PDF of the next value of the sequence can then be approximated as a function of the current value of the sequence and the value of the current hidden state of the RNN.

[//]: # (

P( Y[n+1]=y[n+1] | Y[n]=y[n], H[n]=h[n] ) (2)

Graves describes in detail how to train this to fit many sequential datasets, including Shakespeare’s works, the entire Wikipedia text, and also an online handwriting database. Training uses backpropagation through time along with cross-entropy loss between generated sequences and actual training sequences. Gradient clipping prevents gradients and weights from blowing up.

The fun comes after training the model. If the probability distribution that the RNN produces is close enough to the actual empirical PDF of the data, then we can sample from this distribution and the RNN will generate fake but plausible sequences. This technique became very well known in the past few years, including in political satire (Obama-RNN and @deepdrumpf bots) and generative ASCII art. The sampling illuminates how an RNN can dream.

Conceptual framework for sampling a sequence from an RNN

Text generation has been the most widely used application of this method in recent years. The data is readily available, and the probability distribution can be modeled with a softmax layer. A less explored path is using this approach to generate a sequence of real numbers, including actual sound waveforms, handwriting, and vector art drawings.

The paper experimented with training this RNN model on an online handwriting database, where the data is obtained from recording actual handwriting samples on a digital tablet, stroke-by-stroke, in vectorized format. This is what the examples in the the IAM handwriting dataset look like:

The tablet device records these handwriting samples by representing the handwriting as a whole bunch of small vectors of coordinate offsets. Each vector also has an extra binary state indicating an end of stroke event (i.e. the pen will be lifted up from the screen). After such an event, the next vector will indicate where the following stroke begins.

We can see how the training data looks by visualizing each vector with a random color:

For completeness sake, we can visualise each stroke as well with its own random colour, which looks visually more appealing than visualising each small vector in the training set:

Note that the model trains on each vector, rather than each stroke (which is a collection of vectors until an end of stroke event occurs).

The RNN’s task is to model the conditional joint probability distribution of the next offset coordinates (a pair of real numbers indicating the magnitudes of the offsets) and the end of stroke signal (S, a binary variable).

[//]: # (

P( X[n+1]=x_{n+1}, Y[n+1]=y[n+1], S[n+1]=s[n+1] | X[n]=x[n], Y[n]=y[n], S[n]=s[n], H[n]=h[n] ) (3)

The method outlined in the paper is to approximate the conditional distribution of the X and Y as a mixture gaussian distribution, where many small gaussian distributions are added together, and S is a Bernoulli random variable. This technique of using a neural network to generate the parameters of a mixture distribution was originally developed by Bishop, for feed-forward networks, and this paper extends that approach to RNNs. At each time step, the RNN converts (x[n], y[n], s[n], h[n]) into the parameters of a mixture gaussian PDF, which varies over time as it writes. For example, imagine that the RNN has seen the previous few data points (grey dots), and now it must predict a probability distribution over the location of the next point (the pink regions):

The pen might continue to the current stroke, or it might jump to the right and start a new character. The RNN will model this uncertainty. After fitting this model to the entire IAM database, the RNN can be sampled as described earlier to generate fake handwriting:

We can also try to closely examine the probability distributions that the RNN is outputting during the sampling process. In the example below, in addition to the RNN’s handwriting sample, we also visualise the probability distributions for the offsets (red dots) and end of stroke probability (intensity of grey line) from the samples to understand its thinking process.

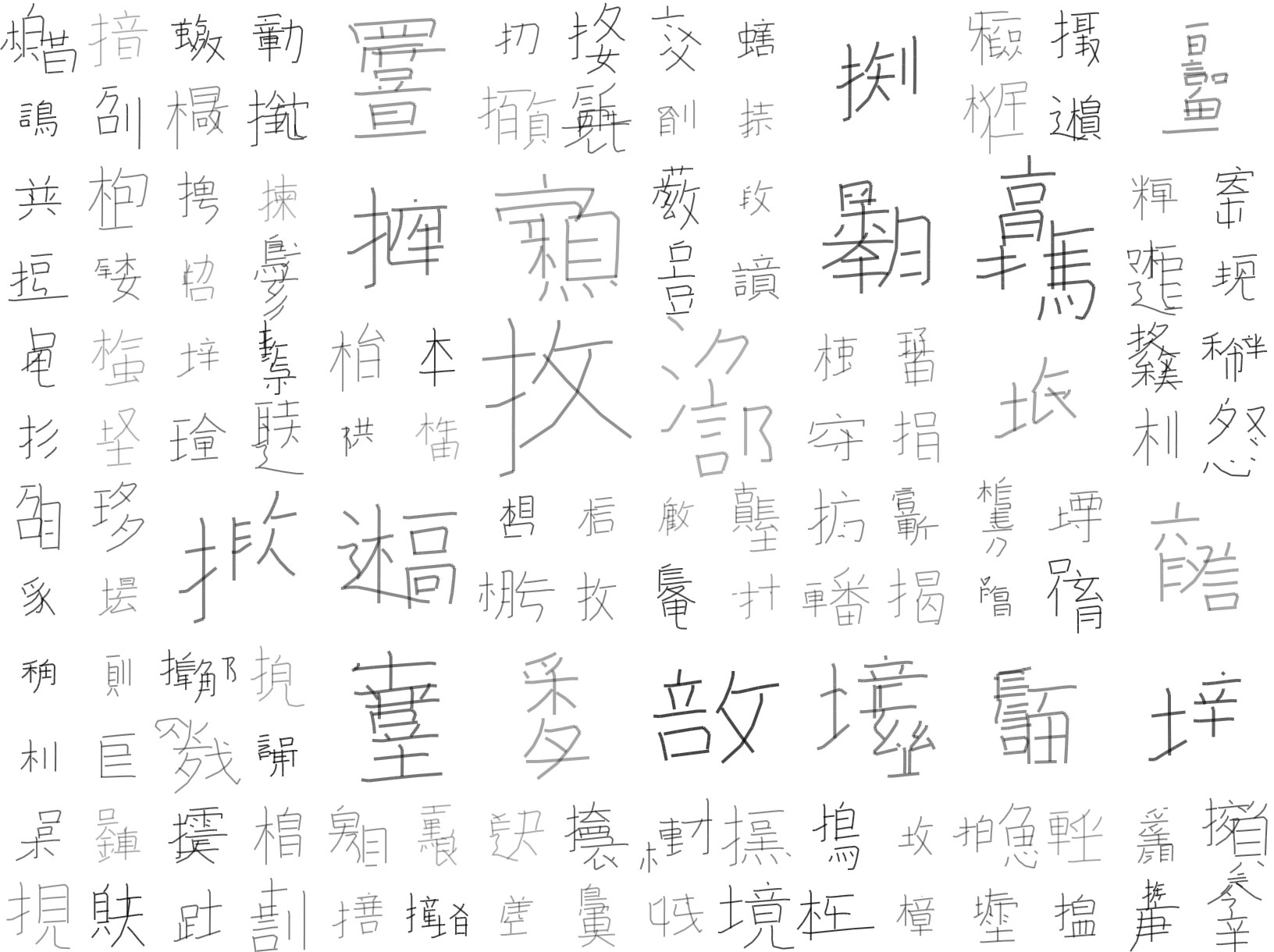

This is quite powerful, and there are a lot of directions to explore by extending this sequential sampling method in the future. For example, a slightly modified version of this RNN can be trained on Chinese character stroke data to generate fictional Chinese characters:

Subsequent sections of Graves’s paper also outline some methods to perform conditional sampling. Here, we give the model access to information about the specific character we want it to write, as well as the previous and next characters so that it can understand the nuances of linking them together.

[//]: # (

P( X[n+1]=x[n+1], Y[n+1]=y[n+1], S[n+1]=s[n+1] | X[n]=x[n], Y[n]=y[n], S[n]=s[n], C[n+1]=c[n+1], C[n]=c[n], C[n-1]=c[n-1], H[n]=h[n] ) (4)

Like all models, this generative RNN model is not without limitations. For example, the model will fail to train on more complicated datasets such as vectorized drawings of animals, due to the more complex and diverse nature of each image. For example, the model needs to learn higher order concepts such as eyes, ears, nose, body, feet and tails when drawing a sketch of an animal. When humans write or draw, most of the time we have some idea in advance about what we want to produce. One shortfall of this model is that the source of randomness is concentrated only at the output layer, so it may not be able to capture and produce many of these high level concepts.

A potential extension to this RNN technique is to convert the RNN into a Variational RNN (VRNN) to model the conditional probability distributions. Using these newer methods, latent variables or thought vectors can be embedded inside the model to control the type of content and style of the outputs. There are some promising preliminary results when applying VRNNs to perform the same handwriting task in Graves’s paper. The generated handwriting samples from the VRNN follow the same handwriting style rather than jump around from one style to another.

In conclusion, this paper introduces a methodology to enable RNNs to act as a generative model, and opens up interesting directions in the area of computer generated content.