-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 2.3k

/

internal.md

347 lines (261 loc) · 11.2 KB

/

internal.md

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

---

sidebar_position: 1

---

# Internal Designs

## Intermediate representation (IR)

Taichi's computation IR is designed to be

- Static-single assignment;

- Hierarchical, instead of LLVM-style control-flow graph + basic blocks;

- Differentiable;

- Statically and strongly typed.

For example, a simple Taichi kernel

```python {4-8} title=show_ir.py

import taichi as ti

ti.init(print_ir=True)

@ti.kernel

def foo():

for i in range(10):

if i < 4:

print(i)

foo()

```

may be compiled into

```

kernel {

$0 = offloaded range_for(0, 10) grid_dim=0 block_dim=32

body {

<i32> $1 = loop $0 index 0

<i32> $2 = const [4]

<i32> $3 = cmp_lt $1 $2

<i32> $4 = const [1]

<i32> $5 = bit_and $3 $4

$6 : if $5 {

print $1, "\n"

}

}

}

```

:::note

Use `ti.init(print_ir=True)` to print IR of all instantiated kernels.

:::

:::note

See [Life of a Taichi kernel](./compilation.md) for more details about

the JIT compilation system of Taichi.

:::

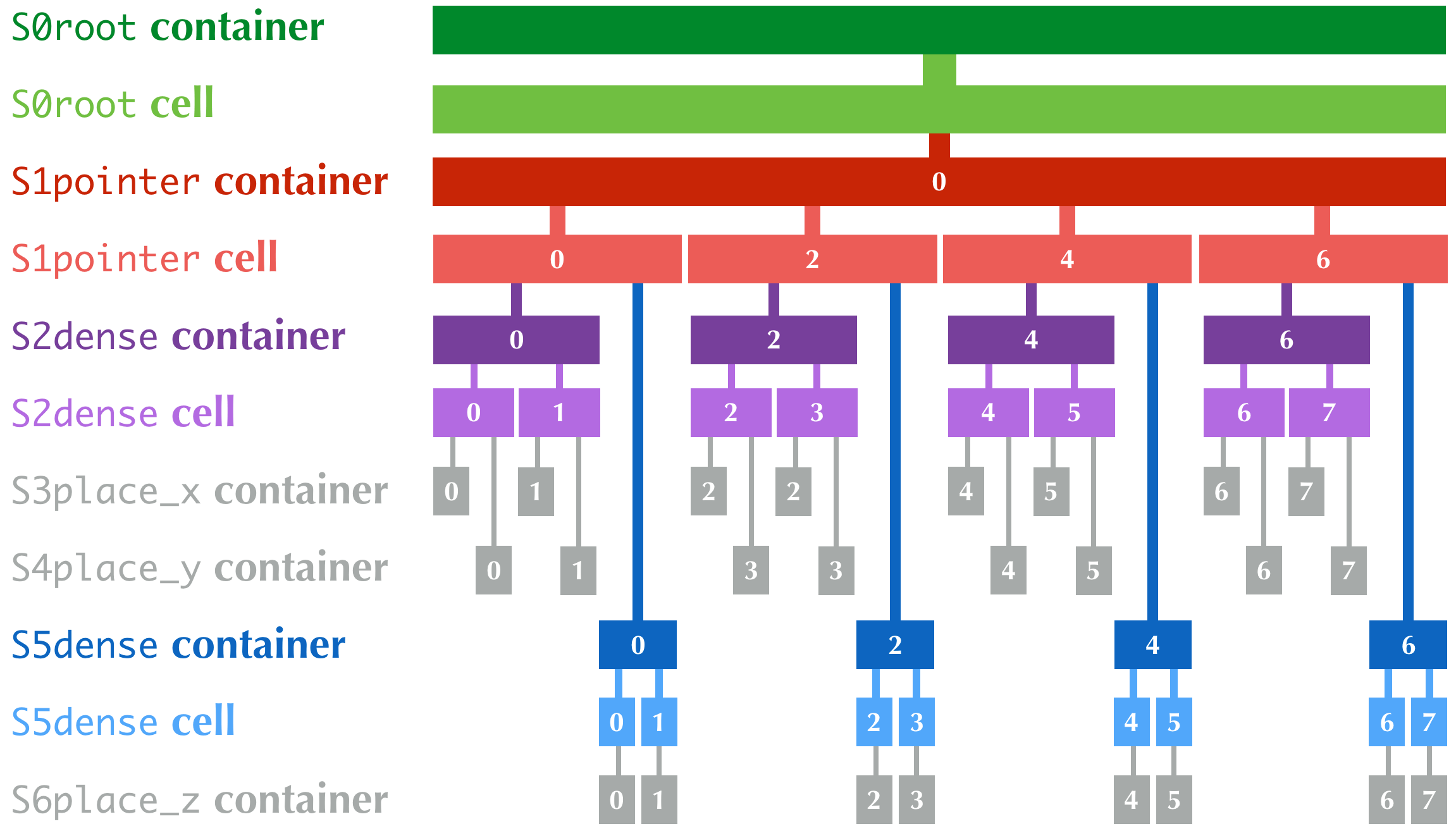

## Data structure organization

The internal organization of Taichi's data structure is defined using the **Structural Node**

("SNode", /snōd/) tree system. The SNode system might be confusing for new developers:

it is important to distinguish three concepts: SNode **containers**,

SNode **cells**, and SNode **components**.

- A SNode **container** can have multiple SNode **cells**. The numbers of

**cells** are recommended to be powers of two.

- For example, `S = ti.root.dense(ti.i, 128)` creates an SNode `S`, and each `S` container has `128` `S` cells.

- A SNode **cell** can have multiple SNode **components**.

- For example, `P = S.dense(ti.i, 4); Q = S.dense(ti.i, 4)` inserts two components (one `P` container and one `Q` container) into each `S` cell.

- Note that each SNode **component** is a SNode **container** of a lower-level SNode.

A hierarchical data structure in Taichi, dense or sparse, is essentially a tree with interleaved container and cell levels.

Note that containers of `place` SNodes do not have cells. Instead, they

directly contain numerical values.

Consider the following example:

```python

# misc/listgen_demo.py

x = ti.field(ti.i32)

y = ti.field(ti.i32)

z = ti.field(ti.i32)

S0 = ti.root

S1 = S0.pointer(ti.i, 4)

S2 = S1.dense(ti.i, 2)

S2.place(x, y) # S3: x; S4: y

S5 = S1.dense(ti.i, 2)

S5.place(z) # S6: z

```

- The whole data structure is an `S0root` **container**, containing

- 1x `S0root` **cell**, which has only one **component**, which

is

- An `S1pointer` **container**, containing

- 4x `S1pointer` **cells**, each with two **components**,

which are

- An `S2dense` **container**, containing

- 2x `S2dense` **cells**, each with two

**components**, which are

- An `S3place_x` container which directly

contains a `x: ti.i32` value

- An `S4place_y` container which directly

contains a `y: ti.i32` value

- An `S5dense` **container**, containing

- 2x `S5dense` **cells**, each with one

**component**, which is

- An `S6place` container which directly

contains a `z: ti.i32` value

The following figure shows the hierarchy of the data structure. The

numbers are `indices` of the containers and cells.

Note that the `S0root` container and cell do not have an `index`.

In summary, we will have the following containers:

- 1x `S0root` container

- 1x `S1pointer` container

- 4x `S2dense` containers

- 4x `S5dense` containers

- 8x `S3place_x` containers, each directly containing an `i32` value

- 8x `S4place_y` containers, each directly containing an `i32` value

- 8x `S6place_z` containers, each directly containing an `i32` value

... and the following cells:

- 1x `S0root` cell

- 4x `S1pointer` cells

- 8x `S2dense` cells

- 8x `S5dense` cells

Again, note that `S3place_x`, `S4place_y` and `S6place_z` containers do **not**

have corresponding cells.

In struct compilers of supported backends, each SNode has two types: `container` type and

`cell` type. Again, **components** of a higher level SNode **cell** are

**containers** of a lower level SNode.

Note that **cells** are never exposed to end-users.

**List generation** generates lists of SNode **containers** (instead of

SNode **cells**).

:::note

We are on our way to remove usages of **children**, **instances**, and

**elements** in Taichi. These are very ambiguous terms and should be replaced with standardized terms: **container**, **cell**, and **component**.

:::

## List generation

Struct-fors in Taichi loop over all active elements of a (sparse) data

structure **in parallel**. Evenly distributing work onto processor cores

is challenging on sparse data structures: naively splitting an irregular

tree into pieces can easily lead to partitions with drastically

different numbers of leaf elements.

Our strategy is to generate lists of active **SNode containers**, layer by

layer. The list generation computation happens on the same device as

normal computation kernels, depending on the `arch` argument when the

user calls `ti.init()`.

List generations flatten the data structure leaf elements into a 1D

list, circumventing the irregularity of incomplete trees. Then we

can simply invoke a regular **parallel for** over the 1D list.

For example,

```python {14-17}

# misc/listgen_demo.py

import taichi as ti

ti.init(print_ir=True)

x = ti.field(ti.i32)

S0 = ti.root

S1 = S0.dense(ti.i, 4)

S2 = S1.bitmasked(ti.i, 4)

S2.place(x)

@ti.kernel

def func():

for i in x:

print(i)

func()

```

gives you the following IR:

```

$0 = offloaded clear_list S1dense

$1 = offloaded listgen S0root->S1dense

$2 = offloaded clear_list S2bitmasked

$3 = offloaded listgen S1dense->S2bitmasked

$4 = offloaded struct_for(S2bitmasked) block_dim=0 {

<i32 x1> $5 = loop index 0

print i, $5

}

```

Note that `func` leads to two list generations:

- (Tasks `$0` and `$1`) based on the list of the (only) `S0root` container,

generate the list of the (only) `S1dense` container;

- (Tasks `$2` and `$3`) based on the list of `S1dense` containers,

generate the list of `S2bitmasked` containers.

The list of `S0root` SNode always has exactly one container, so we

never clear or re-generate this list. Although the list of `S1dense` always

has only one container, we still regenerate the list for uniformity.

The list of `S2bitmasked` has 4 containers.

:::note

The list of `place` (leaf) nodes (e.g., `S3` in this example) is never

generated. Instead, we simply loop over the list of their parent nodes,

and for each parent node we enumerate the `place` nodes on-the-fly

(without actually generating a list).

The motivation for this design is to amortize list generation overhead.

Generating one list element per leaf node (`place` SNode) element is too

expensive, likely much more expensive than the essential computation

happening on the leaf element. Therefore we only generate their parent

element list, so that the list generation cost is amortized over

multiple child elements of a second-to-last-level SNode element.

In the example above, although we have 16 instances of `x`, we only

generate a list of 4 x `S2bitmasked` nodes (and 1 x `S1dense` node).

:::

## Statistics

In some cases, it is helpful to gather certain quantitative information

about internal events during Taichi program execution. The `Statistics`

class is designed for this purpose.

Usage:

```cpp

#include "taichi/util/statistics.h"

// add 1.0 to counter "codegen_offloaded_tasks"

taichi::stat.add("codegen_offloaded_tasks");

// add the number of statements in "ir" to counter "codegen_statements"

taichi::stat.add("codegen_statements", irpass::analysis::count_statements(this->ir));

```

Note the keys are `std::string` and values are `double`.

To print out all statistics in Python:

```python

ti.core.print_stat()

```

## Why Python frontend

Embedding Taichi in `python` has the following advantages:

- Easy to learn. Taichi has a very similar syntax to Python.

- Easy to run. No ahead-of-time compilation is needed.

- This design allows people to reuse existing python infrastructure:

- IDEs. A python IDE mostly works for Taichi with syntax

highlighting, syntax checking, and autocomplete.

- Package manager (pip). A developed Taichi application and be

easily submitted to `PyPI` and others can easily set it up with

`pip`.

- Existing packages. Interacting with other python components

(e.g. `matplotlib` and `numpy`) is just trivial.

- The built-in AST manipulation tools in `python` allow us to flexibly

manipulate and analyze Python ASTs,

as long as the kernel body function is parse-able by the Python parser.

However, this design has drawbacks too:

- Taichi kernels must be parse-able by Python parsers. This means Taichi

syntax cannot go beyond Python syntax.

- For example, indexing is always needed when accessing elements

in Taichi fields, even if the fields is 0D. Use `x[None] = 123`

to set the value in `x` if `x` is 0D. This is because `x = 123`

will set `x` itself (instead of its containing value) to be the

constant `123` in Python syntax. For code consistency in Python-

and Taichi-scope, we have to use the more verbose `x[None] = 123` syntax.

- Python has relatively low performance. This can cause a performance

issue when initializing large Taichi fields with pure python

scripts. A Taichi kernel should be used to initialize huge fields.

## Virtual indices v.s. physical indices

In Taichi, _virtual indices_ are used to locate elements in fields, and

_physical indices_ are used to specify data layouts in memory.

For example,

- In `a[i, j, k]`, `i`, `j`, and `k` are **virtual** indices.

- In `for i, j in x:`, `i` and `j` are **virtual** indices.

- `ti.i, ti.j, ti.k, ti.l, ...` are **physical** indices.

- In struct-for statements, `LoopIndexStmt::index` is a **physical**

index.

The mapping between virtual indices and physical indices for each

`SNode` is stored in `SNode::physical_index_position`. I.e.,

`physical_index_position[i]` answers the question: **which physical

index does the i-th virtual index** correspond to?

Each `SNode` can have a different virtual-to-physical mapping.

`physical_index_position[i] == -1` means the `i`-th virtual index does

not correspond to any physical index in this `SNode`.

`SNode` s in handy dense fields (i.e.,

`a = ti.field(ti.i32, shape=(128, 256, 512))`) have **trivial**

virtual-to-physical mapping, e.g. `physical_index_position[i] = i`.

However, more complex data layouts, such as column-major 2D fields can

lead to `SNodes` with `physical_index_position[0] = 1` and

`physical_index_position[1] = 0`.

```python

a = ti.field(ti.f32, shape=(128, 32, 8))

b = ti.field(ti.f32)

ti.root.dense(ti.j, 32).dense(ti.i, 16).place(b)

ti.lang.impl.get_runtime().materialize() # This is an internal api for dev, we don't make sure it is stable for user.

mapping_a = a.snode().physical_index_position()

assert mapping_a == {0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 2}

mapping_b = b.snode().physical_index_position()

assert mapping_b == {0: 1, 1: 0}

# Note that b is column-major:

# the virtual first index exposed to the user comes second in memory layout.

```

Taichi supports up to 8 (`constexpr int taichi_max_num_indices = 8`)

virtual indices and physical indices.