Summary

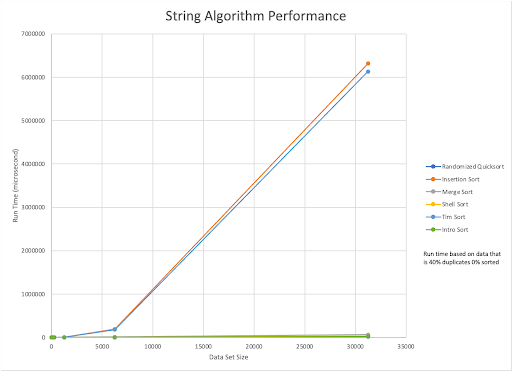

This program implements six different sorting algorithms and compares the performances on different set sizes.

Sorting algorithm implemented:

- Insertion Sort

- Randomized Quicksort

- Merge Sort

- Shell Sort

- Intro Sort

- Tim Sort

In order to generate datasets for our algorithms, we created a Python function that accepted an initial dataset size from the user,

created all of the required datasets for that size, and then multiplied the size by 5. The program then ran an additional 5 times, until we had 6 dataset sizes with each dataset type for a grand total of 30 datasets. We then recorded all generated datasets to input.csv with each dataset on a different line.

The required dataset types were as follows:

randomized dataset of size s with 0% duplicates

dataset of size s with 0% duplicates that is sorted in ascending order

dataset of size s with 0% duplicates such that 60% of the array is already sorted ascending.

randomized dataset of size s with 20% duplicates

randomized dataset of size s with 40% duplicates

To create the datasets, we made a pipeline that first created a list of all of the numbers from 1 to the desired size (Requirement 2). Then, we shuffled 60% of that list (Requirement 3), and then shuffled that list again (Requirement 1). In order to create the datasets with percent duplicates, we created a ‘percentDupe’ function. This function first created a list with numbers from 1 to the percent of the desired size. From there, we extended the list for the leftover percent of the desired size starting with the number 1 again. If the percentages added together exceeded the desired size (often caused by integer division), we popped the list’s final element. This created a list of the desired size with the specified percent of duplicates (Requirements 4 and 5).

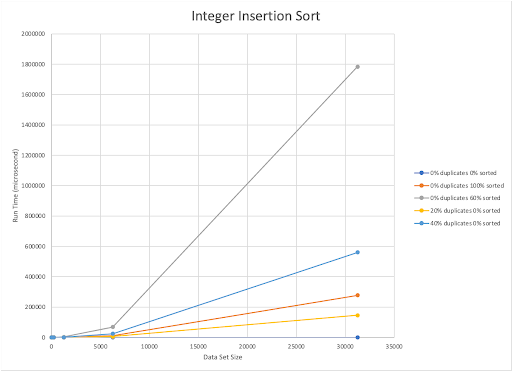

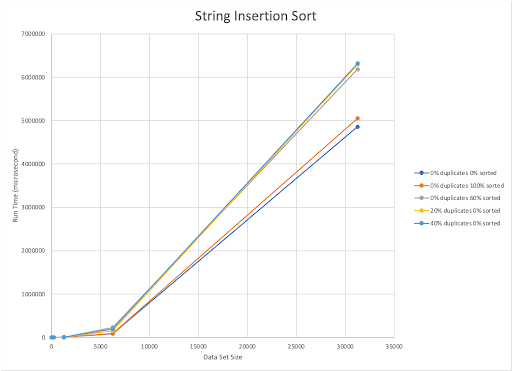

The published upper bound for Insertion Sort is O(n^2). Our implementation is also O(n^2). Our implementation of Insertion Sort worked best with the data set with the dataset with completely unsorted, unique elements. The main effector of our implementation of this algorithm is the percentage of pre-sorted elements already present in the integer dataset. The algorithm seems to react to the integer and string datasets in the same way.

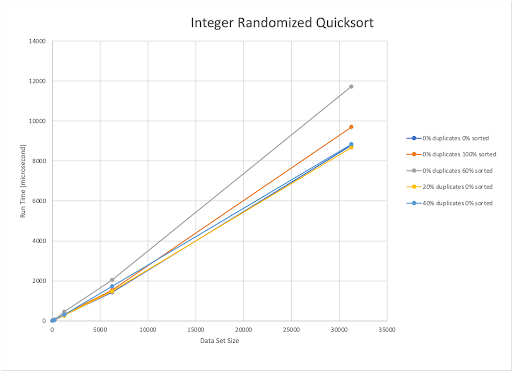

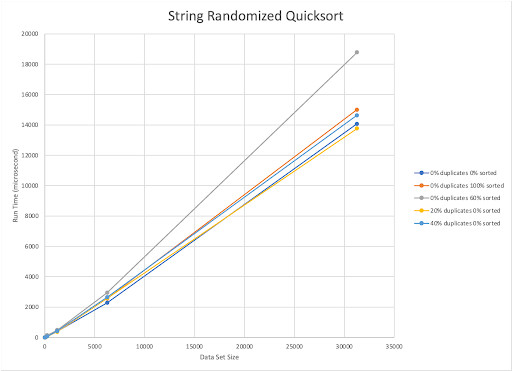

The published upper bound for Randomized Quick Sort is O(nlogn). Our implementation is also O(nlogn). Randomized QuickSort worked quickest when the data set was composed of 20% duplicate elements that are completely unsorted. With this algorithm, as the percentage of unsorted elements increases within the dataset, the run time also increases, regardless of the amount of duplicated elements present.

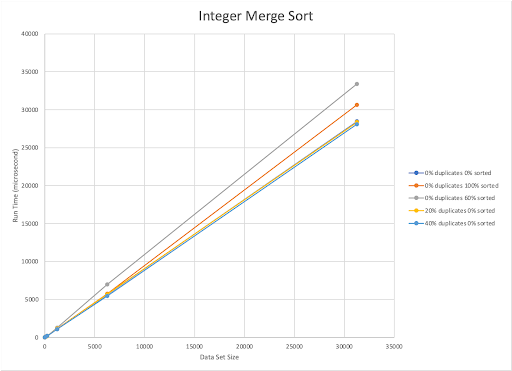

The published upper bound for Merge Sort is O(nlogn). Our implementation is also O(nlogn). Our implementation of Merge Sort worked best with randomized datasets with 40% duplicates. However, it was the slowest for 60% sorted datasets with 0% duplicates. With our Merge Sort, when fewer duplicates were present run time was the largest, even if the dataset was already 100% sorted.

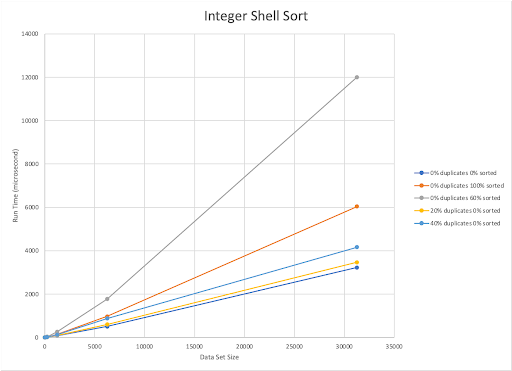

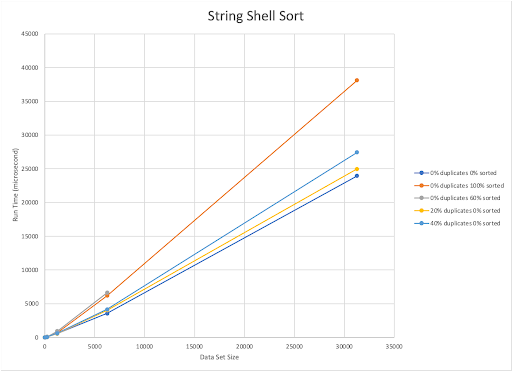

The published upper bound for Shell Sort is O(n^2). Our implementation is also O(n^2). Shell sort worked quickest with a completely unsorted dataset containing 40% duplicated elements. The amount of sorted elements and run time are inversely related. As the percentage of pre-sorted elements decreases, the run time of the algorithm increases.

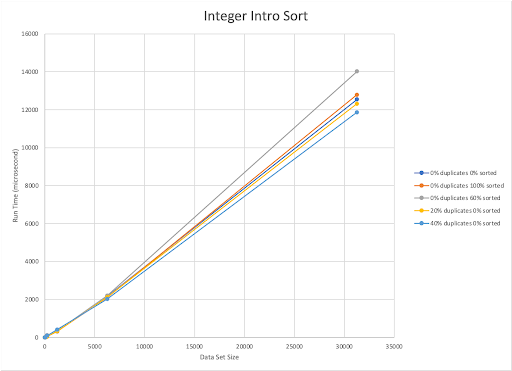

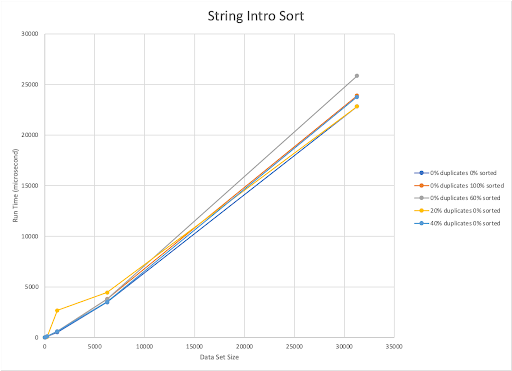

The published upper bound for Intro Sort is O(nlogn). Our implementation is also O(nlogn). For our implementation, as the number of duplicate elements increases the run time gets faster. This sort was slowest for datasets with 0% duplicates 60% sorted. Oddly enough, it appears that the less sorted a dataset was (and with the fewest unique elements), the faster our Intro Sort could sort it.

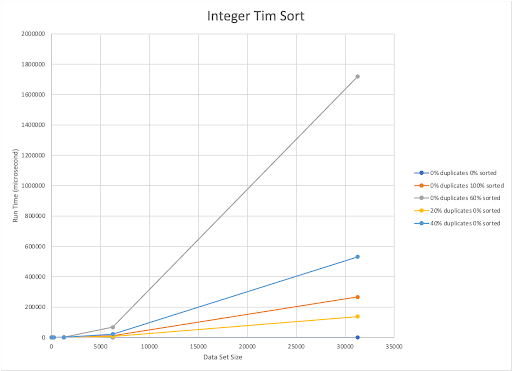

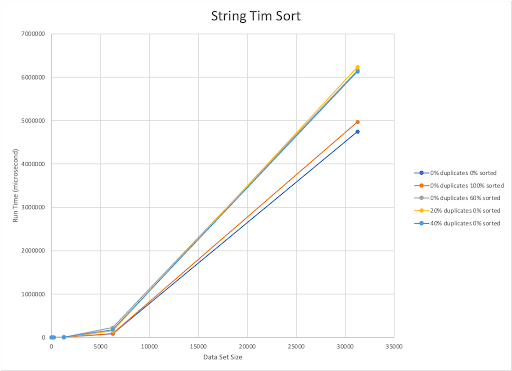

The published upper bound for Tim Sort is O(nlogn). Our implementation is also O(nlogn). The Tim Sort implementation we made was fastest for datasets that were randomized and had no duplicates. This was shared between integers and strings. However, for our integer datasets Tim Sort was slowest on 60% sorted 0% duplicate datasets, and for strings it was slowest for randomized datasets with 20% duplicates. When sorting integers it appears that Tim Sort handles randomized datasets faster than sorted or even partially sorted datasets. This also holds true for strings.

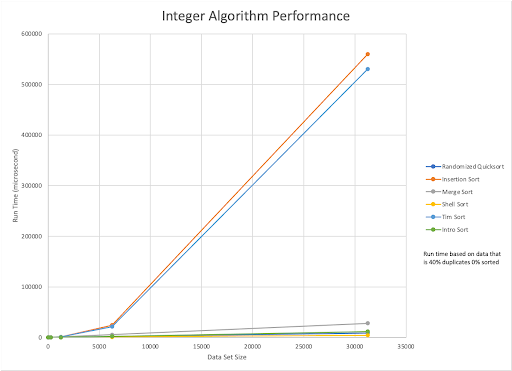

The best sorting algorithm for integers differs between dataset types, but the algorithms that were consistently the fastest were the Intro, Shell and Randomized Quick Sorts. Intro Sort appeared to be the most consistent across the dataset types for smaller sizes (0-6000 elements) but slowed slightly as datasets got larger. Intro Sort was the most effective on randomized datasets with 40% duplicates, and slowest when sorting a 60% sorted dataset with 0% duplicates.

As for Quick Sort, the overall time that sorting took was very small compared to the other sorting algorithms. Quick Sort was the slowest when sorting a 60% sorted dataset with 0% duplicates. Interestingly, it appeared to have been the most effective on the randomized datasets with 20% duplicates.

Overall, however, Shell Sort was the fastest when it came to sorting integers and had the lowest sorting times for the largest dataset.

The best sorting algorithm for strings was Randomized Quick Sort, which outperformed all of the other sorting algorithms for most dataset types. Intro Sort, however, outperformed Quick Sort when using randomized datasets with 40% duplicates.

For all of our sorting algorithms, dataset size greatly affected the time it took to sort. This could be a side effect of our data generation sizes, which exponentially increased, or it could just mean that a larger dataset takes more time to evaluate. On the other hand, it appears that overall strings took more time to sort than integers. Strangely, we noticed that for most of the sorting algorithms the pre-sorted datasets often took more time than we expected.