Scientific journals are a surviving artifact of the last millennium and are slowing down scientific progress. Even though journals also publish online (and some are “Open Access”), the Internet provides far richer capabilities than digitizing a sheet of paper and adding a few hyperlinks. Research should be free to access and easily modifiable to lower the barrier to progress. Some publishers have attempted to remedy these problems in response to market demands, but researchers have their hands tied as they rely on publications to advance their career. In addition, the vast number of publishers each introducing their own business models creates an inconsistent and unproductive environment for research. Industries with open standards best serve the consumer, while publishers continue to best serve their bank accounts. Science needs a common platform to enable modern and global research utilizing the Internet for collaboration, corroboration, and distribution.

STM: International Association of Scientific, Technical, and Medical Publishers cites five reasons why journals are an “integral part of scientific research itself” (Ware and Mabe, 6). They are:

- Disseminate information to intended audiences

- Establish author's precedence

- Maintain quality through peer review

- Provide archival copies for reference and citation

- Navigate large volumes of published material

These characteristics are not unique to a journal and can be provided by other means. Doing so in an open and standardized way will propel science into a modern age.

Publishers seek to maintain quality in scientific publications through peer review, a process designed to select significant and sound research. Submitted papers are first reviewed by an editor who can elect to conduct peer review. Reviews are typically conducted by two or three researchers in the same field as the submitted paper and final discretion is left to the editor whether to accept or reject it. This process varies between the thousands of journals: single-blind, double-blind, pre-publication review, post-publication review, open comments, closed comments, etc. This results in no standard procedure and no clear insight into why a certain paper is accepted or rejected.

The lack of standards provides no guarantees to the quality of the review, yet scientists believe this system is sound. However, editors have been conned into selecting peer reviewers who are the authors themselves or their close friends resulting in a total of 110 retractions between 2012-2014 (Ferguson et al.). While no system is foolproof, readers are forced to put blind faith in the system because it lacks the transparency necessary for public audit. Even when peer review is not gamed, there is still is no reason to believe it selects for significance and sound research. High impact-factor journals like Science are known for publishing important scientific findings. But even a highly respected journal like Science cannot verify the scientific integrity of the articles it publishes. A recent high-profile paper regarding lasting opinion changes after talking with gay or minority canvassers was retracted from Science after the data used was found to be fabricated (LaCour et al.). This case highlights the overconfidence placed in peer review and the potential impact on the malleable public opinion. Science cannot be based on faith of a black-box system; researchers need something a little more scientific.

Publishers charge readers to view articles, or in the case of newer Open Access business models, they charge writers to publish articles. Placing the cost on the reader or writer is detrimental to the dissemination of information. Traditional subscriptions for universities can total extraordinary sums, with Harvard's library paying $3.5m a year in 2012 (Sample). This drains money from universities who face budget shortages and students who face increasing tuition. In addition, personal subscriptions cost hundreds of dollars and prevent those who are not associated with an institution from accessing scientific literature. This group of people includes high school students and members of the general public interested in science. Whether they are conducting their own research or simply looking for a primary source of information, readers should be free to access scientific literature regardless of their economic status or affiliation.

Publishers have attempted to address this issue with variants of the Open Access business model. “Business model” is emphasized here because publishers are businesses at heart and their motives may not align with researchers' best interests. Open Access comes in a variety of flavors but the general shift is to source money from the writers and not the readers. While this does empower the general public to access papers for free, the cost merely shifts to the funding organizations. Grant funds are then funneled directly to the publishers. In addition, independent researchers who cannot afford the thousand dollars to publish an article are excluded from the scientific body. Publishers make science a pay-to-play club, which is a great business model, but a poor research model.

Researchers rely on high profile publications to advance their career and increase their chances of receiving grant funding. There is a surplus of trained graduates who face limited research positions with a shortage of funding. This creates a hyper-competitive market where researchers must focus on projects which are appealing to grant readers and editors alike. These “sexy stories” corner the market and preclude fundamental research which is an unsustainable practice since a “sexy story” builds upon those fundamentals. Removing publishers cannot directly affect grant readers, but it will remove the journal's name from an evaluation. As previously discussed, a paper's acceptance to a particular journal is an inconsistent process and so the importance of journal name is largely a cultural construct.

Journals are ultimately a business and their interests lie in making money, not progressing science. Market demand will not suffice to influence necessary changes because researchers are strangled by publish or perish. There are lots of journals with new schemes that address the above issues; but they are incompatible and layering fixes upon a bad system will only result in a tower of mud. Scientific communication needs to be open and standardized, a result which can only come from the drawing boards.

The core components of an open scientific communication system are as follows:

- Users – professional researchers, hobbyist scientists, students of all levels, the public

- Content – articles, reviews, grant funding, comments, data, source code, etc.

- Ledger – a consistent and verified append-only history of all communications

All content is produced by a user and can be linked to another piece of content. The ledger records the events and associated data on the network (added user A; user A wrote article B; user C edited article B; etc.) and will be hosted by each university, for example. Ledgers will communicate with one another to replicate information and verify the integrity of its contents.

- Establish a core working group dedicated to daily work on the system

- Hold a series of free meetings inviting the international research community to participate in gathering ideas and opinions

- Finalize a specification and write an initial implementation

- Solicit researchers to grow the users and content

A fundamental part of the system will be to establish the identity and authenticity of a user. Researchers currently rely on publishers to verify the identity (where do they work?) and authenticity (are they being impersonated?) of authors. In place of publishers, computers provide these two properties with even stronger guarantees. Any message produced by an identity can be signed and then later verified to prevent fraud and data tampering. A network of people can vouch for the identity of others which creates a web of trust. This would allow, for example, researchers working at a university to all vouch that their colleagues indeed work at the same university.

All communications which happen in the system are public and permanent; edits or deletions are recorded but the full changelog is persistent. This opens the gates for new forms of participation: reviewing reviews, incorporating feedback, accrediting editors, etc. People can be held accountable for what they said and when they said it, which is currently missing from peer review. In addition, data analysis of the network could reveal personal bias and other underlying problems which are currently imperceptible.

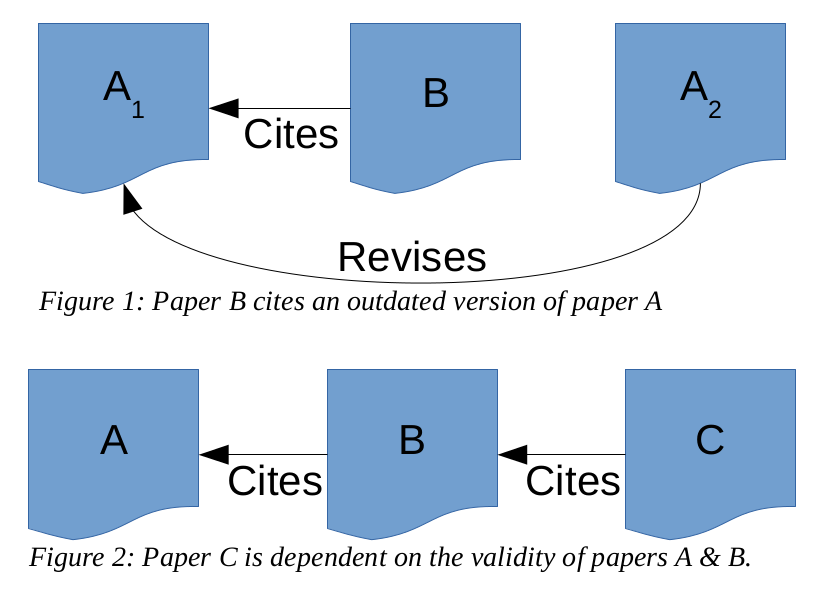

Maintaining a full record of changes to a research paper provides immense power. Consider Figure 1, where paper B cites paper A, but some time later paper A is revised. Paper B may now be citing outdated information and its authors need to be alerted. This issue is magnified when, for example, paper A is retracted in Figure 2. Much like before, paper B needs to be reevaluated but paper C is also at risk for citing bad work. By explicitly tracking the dependencies between papers, computers can help researchers address problems as they arise. While this may be possible today, it will be easily automated in the proposed system.

The communications network will require people or groups to maintain Internet connected servers with the appropriate software. Universities and other institutions are good candidates for this role as it is already standard to maintain e-mail servers. With the money saved from exorbitant subscription costs, there should be little objection to running these servers. Decentralizing the network brings resilience to computer failure as well as balancing network load. The general public can access the system through personal servers, community servers, government servers, or even companies which specializes in hosting.

Articles published on the network should be done under a permissive license to ensure collaboration is the default. It will be necessary to provide authors a suitable license of their choice as to not discourage publication, but preference must be weighed with freedom. The freedoms to distribute and improve upon will foster collaboration and can be seen in other industries. Software companies thrive on developing programs in the open to be improved by others because everyone benefits from the innovations it produces.

Data used in a research paper must be linked to and made available on the network. Much like user identity verification, the integrity of datasets and their changes need to be automatically tracked to promote good standards.

Journals are primarily categorized by their field of study and some may claim that without them, researchers will be lost in the flood of articles. To address these concerns, it will be necessary to provide a set of primitives – ranking, search index, etc. – that will allow more sophisticated navigation of the large amount of content. These capabilities should not be built in, lest they will be unsuitable for the growing needs of researchers. Algorithms can be developed as needed to provide more specific results or show only the more reputable ones, for example. This allows researchers to decide for themselves, if they wish, what is important to them. Editors currently fill this position and do so with unknowable bias and constraints on time and space. There is no stopping self-proclaimed or even professional editors from creating reading lists, but researchers have autonomy in how they wish to explore the literature.

A network of free scientific communication will not only improve upon current systems, but also open the door to new possibilities. For example, researchers play to the interests of editors who want to see big, sexy stories filled with profound impact. This leaves all sorts of research out of the public eye, like small improvements on existing methods and negative or null results. Researchers can learn not only from others' success, but also from their failures. A new system would not suffer the space constraints publishers face today and would allow for new categories of knowledge to be shared. This may even result in a dulling of the idea of publication, as science could be shared on a daily basis and may be viewed as an open research notebook.

While publishers may be obsolete in their current form, there will be a new industry surrounding this system: authors can choose to have their articles formatted or edited by professionals; developers can create new programs to increase productivity; and websites can provide curated collections of articles. Large publishers who face loss of revenue will be forced to adapt to the changing times, a healthy sign of growth. This should also bring power back to the researchers as they will seek out a company based on the quality of their product and not out of necessity.

Scientific research has faced limited funding recently and is only exacerbated by inordinate publisher fees. Scientific journal publishers generated over $25b in revenue worldwide in 2013, a figure nearly equal to the NIH budget (Ware and Mabe, 6) (AAAS). Imagine the immediate benefit if that money were to stay in the hands of researchers and not funneled into the pockets of publishers. Also, by eliminating financial barriers to sharing research, science will develop a new class of global researchers – anyone with an Internet connection – and benefit from their creativity and innovation. The surge in hackerspaces, open source software, maker fairs, and biohackerspaces are proof of the public's curiosity and love of science. It's unfair to exclude this group from participating in research and could accelerate the pace of discovery.

We are soliciting a grant of $1m for a two year period to develop an open standard of a protocol to support scientific research over the Internet and provide an initial implementation for universities and other institutions to begin using. Funding will go towards the full time salary of five team members that is competitive with the programming industry. Community involvement in the development process will ensure a protocol that is useful to the whole scientific body, but will require significant time to manage these communications. A two year period should allow ample time to incorporate feedback before standardization. In addition, a system developed in the open will increase the rate of adoption in the entrenched research community. While the resistance to change may be great from some and even stronger from publishers, the world faces problems which require solutions in the near future. A system to support scientific research at a heightened pace and of greater quality is necessary to meet these challenges.

- Aaas.org,. 'Historical Trends In Federal R&D| AAAS - The World's Largest General Scientific Society'. N.p., 2015. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Andraka, Jack. 'Why Science Journal Paywalls Have To Go - The Student Blog'. The Student Blog. N.p., 2013. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Baker, Monya. 'Irreproducible Biology Research Costs Put At $28 Billion Per Year'. Nature (2015): n. pag. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Ferguson, Cat, Adam Marcus, and Ivan Oransky. 'Publishing: The Peer-Review Scam'. Nature 515.7528 (2014): 480-482. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Harris, Richard. 'U.S. Science Suffering From Booms And Busts In Funding'. NPR.org. N.p., 2014. Web. 11 July 2015.

- LaCour, M. J., and D. P. Green. 'When Contact Changes Minds: An Experiment On Transmission Of Support For Gay Equality'. Science 346.6215 (2014): 1366-1369. Web. 11 July 2015.

- 'Review Rewards'. Nature 514.7522 (2014): 274-274. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Sample, Ian. 'Harvard University Says It Can't Afford Journal Publishers' Prices'. the Guardian. N.p., 2012. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Singh Chawla, Dalmeet. 'Scientist Registry Unveils Plan To Recognize Efforts Of Peer-Reviewers'. Nature (2015): n. pag. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Smith, Richard. 'Peer Review: A Flawed Process At The Heart Of Science And Journals'. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99.4 (2006): 178-182. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Van Noorden, Richard. 'Science Publishing: The Trouble With Retractions'. Nature 478.7367 (2011): 26-28. Web. 11 July 2015.

- Ware, Mark, Mabe, Michael, STM,. The STM Report. 2015. Web. 11 July 2015.