These design patterns are useful for building reliable, scalable, secure applications in the cloud.

Each pattern describes the problem that the pattern addresses, considerations for applying the pattern. However, most of the patterns are relevant to any distributed system, whether hosted on Azure or on other cloud platforms.

Availability is the proportion of time that the system is functional and working, usually measured as a percentage of uptime. It can be affected by system errors, infrastructure problems, malicious attacks, and system load. Cloud applications typically provide users with a service level agreement (SLA), so applications must be designed to maximize availability.

Data management is the key element of cloud applications, and influences most of the quality attributes. Data is typically hosted in different locations and across multiple servers for reasons such as performance, scalability or availability, and this can present a range of challenges. For example, data consistency must be maintained, and data will typically need to be synchronized across different locations.

Good design encompasses factors such as consistency and coherence in component design and deployment, maintainability to simplify administration and development, and reusability to allow components and subsystems to be used in other applications and in other scenarios. Decisions made during the design and implementation phase have a huge impact on the quality and the total cost of ownership of cloud hosted applications and services.

The distributed nature of cloud applications requires a messaging infrastructure that connects the components and services, ideally in a loosely coupled manner in order to maximize scalability. Asynchronous messaging is widely used, and provides many benefits, but also brings challenges such as the ordering of messages, poison message management, idempotency, and more.

Cloud applications run in a remote datacenter where you do not have full control of the infrastructure or, in some cases, the operating system. This can make management and monitoring more difficult than an on-premises deployment. Applications must expose runtime information that administrators and operators can use to manage and monitor the system, as well as supporting changing business requirements and customization without requiring the application to be stopped or redeployed.

Performance is an indication of the responsiveness of a system to execute any action within a given time interval, while scalability is ability of a system either to handle increases in load without impact on performance or for the available resources to be readily increased. Cloud applications typically encounter variable workloads and peaks in activity. Predicting these, especially in a multitenant scenario, is almost impossible. Instead, applications should be able to scale out within limits to meet peaks in demand, and scale in when demand decreases. Scalability concerns not just compute instances, but other elements such as data storage, messaging infrastructure, and more.

Resiliency is the ability of a system to gracefully handle and recover from failures. The nature of cloud hosting, where applications are often multitenant, use shared platform services, compete for resources and bandwidth, communicate over the Internet, and run on commodity hardware means there is an increased likelihood that both transient and more permanent faults will arise. Detecting failures, and recovering quickly and efficiently, is necessary to maintain resiliency.

Security is the capability of a system to prevent malicious or accidental actions outside of the designed usage, and to prevent disclosure or loss of information. Cloud applications are exposed on the Internet outside trusted on-premises boundaries, are often open to the public, and may serve untrusted users. Applications must be designed and deployed in a way that protects them from malicious attacks, restricts access to only approved users, and protects sensitive data.

| Category | Pattern | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Geodes | Deploy backend services into a set of geographical nodes, each of which can service any client request in any region. |

| Availability | Health Endpoint Monitoring Pattern | Implement functional checks in an application that external tools can access through exposed endpoints at regular intervals. |

| Availability | Queue-Based Load Leveling Pattern | Use a queue that acts as a buffer between a task and a service that it invokes, to smooth intermittent heavy loads. |

| Availability | Throttling Pattern | Control the consumption of resources by an instance of an application, an individual tenant, or an entire service. |

| Data Management | Cache-Aside Pattern | Load data on demand into a cache from a data store |

| Data Management | Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) Pattern | Segregate operations that read data from operations that update data by using separate interfaces. |

| Data Management | Event Sourcing Pattern | Use an append-only store to record the full series of events that describe actions taken on data in a domain |

| Data Management | Index Table Pattern | Create indexes over the fields in data stores that are frequently referenced by queries. |

| Data Management | Materialized View Pattern | Generate prepopulated views over the data in one or more data stores when the data isn't ideally formatted for required query operations. |

| Data Management | Sharding Pattern | Divide a data store into a set of horizontal partitions or shards. |

| Data Management | Static Content Hosting Pattern | Deploy static content to a cloud-based storage service that can deliver them directly to the client. |

| Data Management | Valet Key Pattern | Use a token or key that provides clients with restricted direct access to a specific resource or service. |

|

Design and Implementation |

Ambassador Pattern | Create helper services that send network requests on behalf of a consumer service or application. |

| Design and Implementation | Anti-Corruption Layer Pattern | Implement a façade or adapter layer between a modern application and a legacy system. |

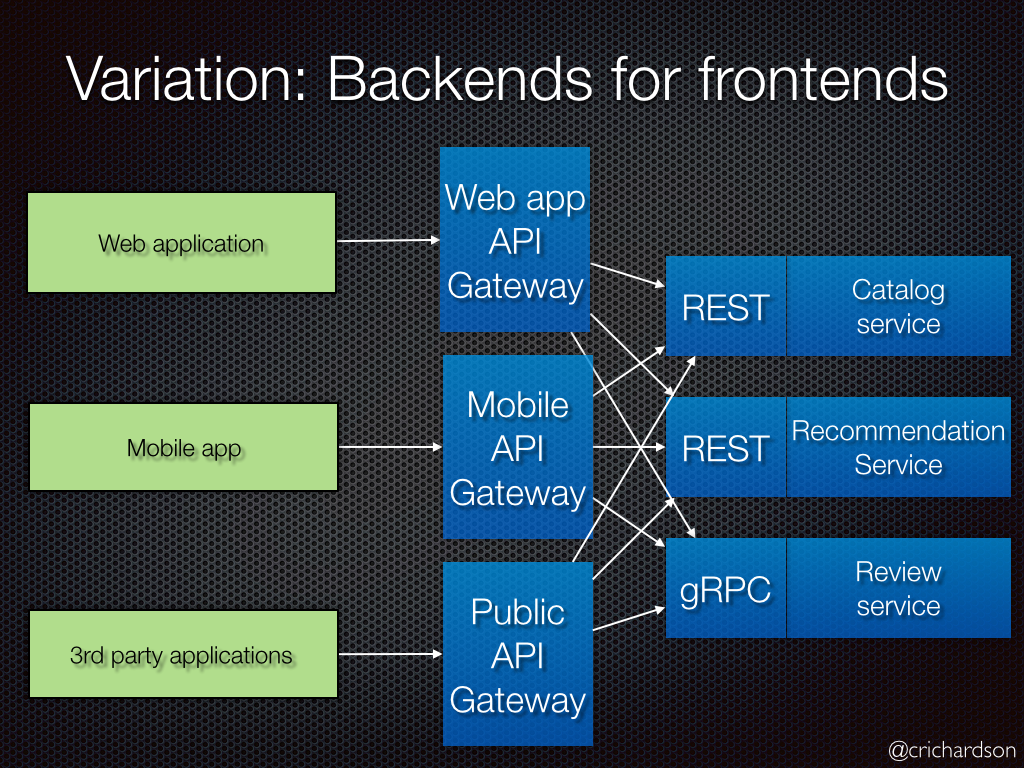

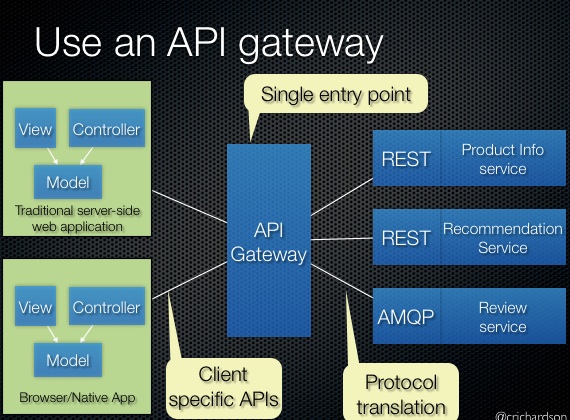

| Design and Implementation | Backends for Frontends Pattern | Create separate backend services to be consumed by specific frontend applications or interfaces. |

| Design and Implementation | Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) Pattern | Segregate operations that read data from operations that update data by using separate interfaces |

| Compute Resource Consolidation Pattern | ||

| External Configuration Store Pattern | ||

| Gateway Aggregation Pattern | ||

| Gateway Offloading Pattern | ||

| Gateway Routing Pattern | ||

| Leader Election Pattern | ||

| Pipes and Filters Pattern | ||

| Sidecar Pattern | ||

| Static Content Hosting Pattern | ||

| Strangler Pattern | ||

| Ambassador Pattern | ||

| Anti-Corruption Layer Pattern | ||

| External Configuration Store Pattern | ||

| Gateway Aggregation Pattern | ||

| Gateway Offloading Pattern | ||

| Gateway Routing Pattern | ||

| Health Endpoint Monitoring Pattern | ||

| Sidecar Pattern | ||

| Strangler Pattern | ||

| Asynchronous Request-Reply Pattern | ||

| Claim-Check Pattern | ||

| Choreography Pattern | ||

| Competing Consumers Pattern | ||

| Pipes and Filters Pattern | ||

| Priority Queue Pattern | ||

| Publisher-Subscriber Pattern | ||

| Queue-Based Load Leveling Pattern | ||

| Scheduler Agent Supervisor Pattern | ||

| Sequential Convoy Pattern | ||

| Cache-Aside Pattern | ||

| Choreography Pattern | ||

| Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) Pattern | ||

| Event Sourcing Pattern | ||

| Geodes | ||

| Index Table Pattern | ||

| Materialized View Pattern | ||

| Priority Queue Pattern | ||

| Queue-Based Load Leveling Pattern | ||

| Sharding Pattern | ||

| Static Content Hosting Pattern | ||

| Throttling Pattern | ||

| Bulkhead Pattern | ||

| Circuit Breaker Pattern | ||

| Compensating Transaction Pattern | ||

| Health Endpoint Monitoring Pattern | ||

| Leader Election Pattern | ||

| Queue-Based Load Leveling Pattern | ||

| Retry Pattern | ||

| Scheduler Agent Supervisor Pattern | ||

| Federated Identity Pattern | ||

| Gatekeeper Pattern | ||

| Valet Key Pattern |

Create helper services that send network requests on behalf of a consumer service or application. An ambassador service can be thought of as an out-of-process proxy that is co-located with the client.

This pattern can be useful for offloading common client connectivity tasks such as monitoring, logging, routing, security (such as TLS), and resiliency patterns in a language agnostic way. It is often used with legacy applications, or other applications that are difficult to modify, in order to extend their networking capabilities. It can also enable a specialized team to implement those features.

Resilient cloud-based applications require features such as circuit breaking, routing, metering and monitoring, and the ability to make network-related configuration updates. It may be difficult or impossible to update legacy applications or existing code libraries to add these features, because the code is no longer maintained or can't be easily modified by the development team.

Network calls may also require substantial configuration for connection, authentication, and authorization. If these calls are used across multiple applications, built using multiple languages and frameworks, the calls must be configured for each of these instances. In addition, network and security functionality may need to be managed by a central team within your organization. With a large code base, it can be risky for that team to update application code they aren't familiar with.

Put client frameworks and libraries into an external process that acts as a proxy between your application and external services. Deploy the proxy on the same host environment as your application to allow control over routing, resiliency, security features, and to avoid any host-related access restrictions. You can also use the ambassador pattern to standardize and extend instrumentation. The proxy can monitor performance metrics such as latency or resource usage, and this monitoring happens in the same host environment as the application.

Features that are offloaded to the ambassador can be managed independently of the application. You can update and modify the ambassador without disturbing the application's legacy functionality. It also allows for separate, specialized teams to implement and maintain security, networking, or authentication features that have been moved to the ambassador.

Ambassador services can be deployed as a sidecar to accompany the lifecycle of a consuming application or service. Alternatively, if an ambassador is shared by multiple separate processes on a common host, it can be deployed as a daemon or Windows service. If the consuming service is containerized, the ambassador should be created as a separate container on the same host, with the appropriate links configured for communication.

- The proxy adds some latency overhead. Consider whether a client library, invoked directly by the application, is a better approach.

- Consider the possible impact of including generalized features in the proxy. For example, the ambassador could handle retries, but that might not be safe unless all operations are idempotent.

- Consider a mechanism to allow the client to pass some context to the proxy, as well as back to the client. For example, include HTTP request headers to opt out of retry or specify the maximum number of times to retry.

- Consider how you will package and deploy the proxy.

- Consider whether to use a single shared instance for all clients or an instance for each client.

Use this pattern when you:

- Need to build a common set of client connectivity features for multiple languages or frameworks.

- Need to offload cross-cutting client connectivity concerns to infrastructure developers or other more specialized teams.

- Need to support cloud or cluster connectivity requirements in a legacy application or an application that is difficult to modify.

This pattern may not be suitable:

- When network request latency is critical. A proxy will introduce some overhead, although minimal, and in some cases this may affect the application.

- When client connectivity features are consumed by a single language. In that case, a better option might be a client library that is distributed to the development teams as a package.

- When connectivity features cannot be generalized and require deeper integration with the client application.

Create helper services that send network requests on behalf of a consumer service or application. An ambassador service can be thought of as an out-of-process proxy that is co-located with the client.

This pattern can be useful for offloading common client connectivity tasks such as monitoring, logging, routing, security (such as TLS), and resiliency patterns in a language agnostic way. It is often used with legacy applications, or other applications that are difficult to modify, in order to extend their networking capabilities. It can also enable a specialized team to implement those features.

Resilient cloud-based applications require features such as circuit breaking, routing, metering and monitoring, and the ability to make network-related configuration updates. It may be difficult or impossible to update legacy applications or existing code libraries to add these features, because the code is no longer maintained or can't be easily modified by the development team.

Network calls may also require substantial configuration for connection, authentication, and authorization. If these calls are used across multiple applications, built using multiple languages and frameworks, the calls must be configured for each of these instances. In addition, network and security functionality may need to be managed by a central team within your organization. With a large code base, it can be risky for that team to update application code they aren't familiar with.

Put client frameworks and libraries into an external process that acts as a proxy between your application and external services. Deploy the proxy on the same host environment as your application to allow control over routing, resiliency, security features, and to avoid any host-related access restrictions. You can also use the ambassador pattern to standardize and extend instrumentation. The proxy can monitor performance metrics such as latency or resource usage, and this monitoring happens in the same host environment as the application.

Features that are offloaded to the ambassador can be managed independently of the application. You can update and modify the ambassador without disturbing the application's legacy functionality. It also allows for separate, specialized teams to implement and maintain security, networking, or authentication features that have been moved to the ambassador.

Ambassador services can be deployed as a sidecar to accompany the lifecycle of a consuming application or service. Alternatively, if an ambassador is shared by multiple separate processes on a common host, it can be deployed as a daemon or Windows service. If the consuming service is containerized, the ambassador should be created as a separate container on the same host, with the appropriate links configured for communication.

- The proxy adds some latency overhead. Consider whether a client library, invoked directly by the application, is a better approach.

- Consider the possible impact of including generalized features in the proxy. For example, the ambassador could handle retries, but that might not be safe unless all operations are idempotent.

- Consider a mechanism to allow the client to pass some context to the proxy, as well as back to the client. For example, include HTTP request headers to opt out of retry or specify the maximum number of times to retry.

- Consider how you will package and deploy the proxy.

- Consider whether to use a single shared instance for all clients or an instance for each client.

Use this pattern when you:

- Need to build a common set of client connectivity features for multiple languages or frameworks.

- Need to offload cross-cutting client connectivity concerns to infrastructure developers or other more specialized teams.

- Need to support cloud or cluster connectivity requirements in a legacy application or an application that is difficult to modify.

This pattern may not be suitable:

- When network request latency is critical. A proxy will introduce some overhead, although minimal, and in some cases this may affect the application.

- When client connectivity features are consumed by a single language. In that case, a better option might be a client library that is distributed to the development teams as a package.

- When connectivity features cannot be generalized and require deeper integration with the client application.

Decouple backend processing from a frontend host, where backend processing needs to be asynchronous, but the frontend still needs a clear response.

In modern application development, it's normal for client applications --- often code running in a web-client (browser) --- to depend on remote APIs to provide business logic and compose functionality. These APIs may be directly related to the application or may be shared services provided by a third party. Commonly these API calls take place over the HTTP(S) protocol and follow REST semantics.

In most cases, APIs for a client application are designed to respond quickly, on the order of 100 ms or less. Many factors can affect the response latency, including:

- An application's hosting stack

- Security components

- The relative geographic location of the caller and the backend

- Network infrastructure

- Current load

- The size of the request payload

- Processing queue length

- The time for the backend to process the request

Any of these factors can add latency to the response. Some can be mitigated by scaling out the backend. Others, such as network infrastructure, are largely out of the control of the application developer. Most APIs can respond quickly enough for responses to arrive back over the same connection. Application code can make a synchronous API call in a non-blocking way, giving the appearance of asynchronous processing, which is recommended for I/O-bound operations.

In some scenarios, however, the work done by backend may be long-running, on the order of seconds, or might be a background process that is executed in minutes or even hours. In that case, it isn't feasible to wait for the work to complete before responding to the request. This situation is a potential problem for any synchronous request-reply pattern.

Some architectures solve this problem by using a message broker to separate the request and response stages. This separation is often achieved by use of the Queue Based Load Leveling Pattern. This separation can allow the client process and the backend API to scale independently. But this separation also brings additional complexity when the client requires success notification, as this step needs to become asynchronous.

Many of the same considerations discussed for client applications also apply for server-to-server REST API calls in distributed systems --- for example, in a microservices architecture.

One solution to this problem is to use HTTP polling. Polling is useful to client-side code, as it can be hard to provide call-back endpoints or use long running connections. Even when callbacks are possible, the extra libraries and services that are required can sometimes add too much extra complexity.

- The client application makes a synchronous call to the API, triggering a long-running operation on the backend.

- The API responds synchronously as quickly as possible. It returns an HTTP 202 (Accepted) status code, acknowledging that the request has been received for processing. Note: The API should validate both the request and the action to be performed before starting the long running process. If the request is invalid, reply immediately with an error code such as HTTP 400 (Bad Request).

- The response holds a location reference pointing to an endpoint that the client can poll to check for the result of the long running operation.

- The API offloads processing to another component, such as a message queue.

- While the work is still pending, the status endpoint returns HTTP 202. Once the work is complete, the status endpoint can either return a resource that indicates completion, or redirect to another resource URL. For example, if the asynchronous operation creates a new resource, the status endpoint would redirect to the URL for that resource.

The following diagram shows a typical flow:

- The client sends a request and receives an HTTP 202 (Accepted) response.

- The client sends an HTTP GET request to the status endpoint. The work is still pending, so this call also returns HTTP 202.

- At some point, the work is complete and the status endpoint returns 302 (Found) redirecting to the resource.

- The client fetches the resource at the specified URL.

- There are a number of possible ways to implement this pattern over HTTP and not all upstream services have the same semantics. For example, most services won't return an HTTP 202 response back from a GET method when a remote process hasn't finished. Following pure REST semantics, they should return HTTP 404 (Not Found). This response makes sense when you consider the result of the call isn't present yet.

- An HTTP 202 response should indicate the location and frequency that the client should poll for the response. It should have the following additional headers:

| Header | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Location | A URL the client should poll for a response status. | This URL could be a SAS token with the Valet Key Pattern being appropriate if this location needs access control. The valet key pattern is also valid when response polling needs offloading to another backend |

| Retry-After | An estimate of when processing will complete | This header is designed to prevent polling clients from overwhelming the back-end with retries. |

- You may need to use a processing proxy or facade to manipulate the response headers or payload depending on the underlying services used.

- If the status endpoint redirects on completion, either HTTP 302 or HTTP 303 are appropriate return codes, depending on the exact semantics you support.

- Upon successful processing, the resource specified by the Location header should return an appropriate HTTP response code such as 200 (OK), 201 (Created), or 204 (No Content).

- If an error occurs during processing, persist the error at the resource URL described in the Location header and ideally return an appropriate response code to the client from that resource (4xx code).

- Not all solutions will implement this pattern in the same way and some services will include additional or alternate headers. For example, Azure Resource Manager uses a modified variant of this pattern. For more information, see Azure Resource Manager Async Operations.

- Legacy clients might not support this pattern. In that case, you might need to place a facade over the asynchronous API to hide the asynchronous processing from the original client. For example, Azure Logic Apps supports this pattern natively can be used as an integration layer between an asynchronous API and a client that makes synchronous calls. See Perform long-running tasks with the webhook action pattern.

- In some scenarios, you might want to provide a way for clients to cancel a long-running request. In that case, the backend service must support some form of cancellation instruction.

Use this pattern for:

- Client-side code, such as browser applications, where it's difficult to provide call-back endpoints, or the use of long-running connections adds too much additional complexity.

- Service calls where only the HTTP protocol is available and the return service can't fire callbacks because of firewall restrictions on the client-side.

- Service calls that need to be integrated with legacy architectures that don't support modern callback technologies such as WebSockets or webhooks.

This pattern might not be suitable when:

- You can use a service built for asynchronous notifications instead, such as Azure Event Grid.

- Responses must stream in real time to the client.

- The client needs to collect many results, and received latency of those results is important. Consider a service bus pattern instead.

- You can use server-side persistent network connections such as WebSockets or SignalR. These services can be used to notify the caller of the result.

- The network design allows you to open up ports to receive asynchronous callbacks or webhooks.

Create separate backend services to be consumed by specific frontend applications or interfaces. This pattern is useful when you want to avoid customizing a single backend for multiple interfaces. This pattern was first described by Sam Newman.

An application may initially be targeted at a desktop web UI. Typically, a backend service is developed in parallel that provides the features needed for that UI. As the application's user base grows, a mobile application is developed that must interact with the same backend. The backend service becomes a general-purpose backend, serving the requirements of both the desktop and mobile interfaces.

But the capabilities of a mobile device differ significantly from a desktop browser, in terms of screen size, performance, and display limitations. As a result, the requirements for a mobile application backend differ from the desktop web UI.

These differences result in competing requirements for the backend. The backend requires regular and significant changes to serve both the desktop web UI and the mobile application. Often, separate interface teams work on each frontend, causing the backend to become a bottleneck in the development process. Conflicting update requirements, and the need to keep the service working for both frontends, can result in spending a lot of effort on a single deployable resource.

As the development activity focuses on the backend service, a separate team may be created to manage and maintain the backend. Ultimately, this results in a disconnect between the interface and backend development teams, placing a burden on the backend team to balance the competing requirements of the different UI teams. When one interface team requires changes to the backend, those changes must be validated with other interface teams before they can be integrated into the backend.

Create one backend per user interface. Fine-tune the behavior and performance of each backend to best match the needs of the frontend environment, without worrying about affecting other frontend experiences.

Because each backend is specific to one interface, it can be optimized for that interface. As a result, it will be smaller, less complex, and likely faster than a generic backend that tries to satisfy the requirements for all interfaces. Each interface team has autonomy to control their own backend and doesn't rely on a centralized backend development team. This gives the interface team flexibility in language selection, release cadence, prioritization of workload, and feature integration in their backend.

For more information, see Pattern: Backends For Frontends.

- onsider how many backends to deploy.

- If different interfaces (such as mobile clients) will make the same requests, consider whether it is necessary to implement a backend for each interface, or if a single backend will suffice.

- Code duplication across services is highly likely when implementing this pattern.

- Frontend-focused backend services should only contain client-specific logic and behavior. General business logic and other global features should be managed elsewhere in your application.

- Think about how this pattern might be reflected in the responsibilities of a development team.

- Consider how long it will take to implement this pattern. Will the effort of building the new backends incur technical debt, while you continue to support the existing generic backend?

Use this pattern when:

- A shared or general purpose backend service must be maintained with significant development overhead.

- You want to optimize the backend for the requirements of specific client interfaces.

- Customizations are made to a general-purpose backend to accommodate multiple interfaces.

- An alternative language is better suited for the backend of a different user interface.

This pattern may not be suitable:

- When interfaces make the same or similar requests to the backend.

- When only one interface is used to interact with the backend.

The Bulkhead pattern is a type of application design that is tolerant of failure. In a bulkhead architecture, elements of an application are isolated into pools so that if one fails, the others will continue to function. It's named after the sectioned partitions (bulkheads) of a ship's hull. If the hull of a ship is compromised, only the damaged section fills with water, which prevents the ship from sinking.

A cloud-based application may include multiple services, with each service having one or more consumers. Excessive load or failure in a service will impact all consumers of the service.

Moreover, a consumer may send requests to multiple services simultaneously, using resources for each request. When the consumer sends a request to a service that is misconfigured or not responding, the resources used by the client's request may not be freed in a timely manner. As requests to the service continue, those resources may be exhausted. For example, the client's connection pool may be exhausted. At that point, requests by the consumer to other services are affected. Eventually the consumer can no longer send requests to other services, not just the original unresponsive service.

The same issue of resource exhaustion affects services with multiple consumers. A large number of requests originating from one client may exhaust available resources in the service. Other consumers are no longer able to consume the service, causing a cascading failure effect.

Partition service instances into different groups, based on consumer load and availability requirements. This design helps to isolate failures, and allows you to sustain service functionality for some consumers, even during a failure.

A consumer can also partition resources, to ensure that resources used to call one service don't affect the resources used to call another service. For example, a consumer that calls multiple services may be assigned a connection pool for each service. If a service begins to fail, it only affects the connection pool assigned for that service, allowing the consumer to continue using the other services.

The benefits of this pattern include:

- Isolates consumers and services from cascading failures. An issue affecting a consumer or service can be isolated within its own bulkhead, preventing the entire solution from failing.

- Allows you to preserve some functionality in the event of a service failure. Other services and features of the application will continue to work.

- Allows you to deploy services that offer a different quality of service for consuming applications. A high-priority consumer pool can be configured to use high-priority services.

The following diagram shows bulkheads structured around connection pools that call individual services. If Service A fails or causes some other issue, the connection pool is isolated, so only workloads using the thread pool assigned to Service A are affected. Workloads that use Service B and C are not affected and can continue working without interruption.

The next diagram shows multiple clients calling a single service. Each client is assigned a separate service instance. Client 1 has made too many requests and overwhelmed its instance. Because each service instance is isolated from the others, the other clients can continue making calls.

- Define partitions around the business and technical requirements of the application.

- When partitioning services or consumers into bulkheads, consider the level of isolation offered by the technology as well as the overhead in terms of cost, performance and manageability.

- Consider combining bulkheads with retry, circuit breaker, and throttling patterns to provide more sophisticated fault handling.

- When partitioning consumers into bulkheads, consider using processes, thread pools, and semaphores. Projects like resilience4j and Polly offer a framework for creating consumer bulkheads.

- When partitioning services into bulkheads, consider deploying them into separate virtual machines, containers, or processes. Containers offer a good balance of resource isolation with fairly low overhead.

- Services that communicate using asynchronous messages can be isolated through different sets of queues. Each queue can have a dedicated set of instances processing messages on the queue, or a single group of instances using an algorithm to dequeue and dispatch processing.

- Determine the level of granularity for the bulkheads. For example, if you want to distribute tenants across partitions, you could place each tenant into a separate partition, or put several tenants into one partition.

- Monitor each partition's performance and SLA.

- Isolate resources used to consume a set of backend services, especially if the application can provide some level of functionality even when one of the services is not responding.

- Isolate critical consumers from standard consumers.

- Protect the application from cascading failures.

This pattern may not be suitable when:

- Less efficient use of resources may not be acceptable in the project.

- The added complexity is not necessary

Load data on demand into a cache from a data store. This can improve performance and also helps to maintain consistency between data held in the cache and data in the underlying data store.

Applications use a cache to improve repeated access to information held in a data store. However, it's impractical to expect that cached data will always be completely consistent with the data in the data store. Applications should implement a strategy that helps to ensure that the data in the cache is as up-to-date as possible, but can also detect and handle situations that arise when the data in the cache has become stale.

Many commercial caching systems provide read-through and write-through/write-behind operations. In these systems, an application retrieves data by referencing the cache. If the data isn't in the cache, it's retrieved from the data store and added to the cache. Any modifications to data held in the cache are automatically written back to the data store as well.

For caches that don't provide this functionality, it's the responsibility of the applications that use the cache to maintain the data.

An application can emulate the functionality of read-through caching by implementing the cache-aside strategy. This strategy loads data into the cache on demand. The figure illustrates using the Cache-Aside pattern to store data in the cache.

If an application updates information, it can follow the write-through strategy by making the modification to the data store, and by invalidating the corresponding item in the cache.

When the item is next required, using the cache-aside strategy will cause the updated data to be retrieved from the data store and added back into the cache.

Consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

Lifetime of cached data. Many caches implement an expiration policy that invalidates data and removes it from the cache if it's not accessed for a specified period. For cache-aside to be effective, ensure that the expiration policy matches the pattern of access for applications that use the data. Don't make the expiration period too short because this can cause applications to continually retrieve data from the data store and add it to the cache. Similarly, don't make the expiration period so long that the cached data is likely to become stale. Remember that caching is most effective for relatively static data, or data that is read frequently.

Evicting data. Most caches have a limited size compared to the data store where the data originates, and they'll evict data if necessary. Most caches adopt a least-recently-used policy for selecting items to evict, but this might be customizable. Configure the global expiration property and other properties of the cache, and the expiration property of each cached item, to ensure that the cache is cost effective. It isn't always appropriate to apply a global eviction policy to every item in the cache. For example, if a cached item is very expensive to retrieve from the data store, it can be beneficial to keep this item in the cache at the expense of more frequently accessed but less costly items.

Priming the cache. Many solutions prepopulate the cache with the data that an application is likely to need as part of the startup processing. The Cache-Aside pattern can still be useful if some of this data expires or is evicted.

Consistency. Implementing the Cache-Aside pattern doesn't guarantee consistency between the data store and the cache. An item in the data store can be changed at any time by an external process, and this change might not be reflected in the cache until the next time the item is loaded. In a system that replicates data across data stores, this problem can become serious if synchronization occurs frequently.

Local (in-memory) caching. A cache could be local to an application instance and stored in-memory. Cache-aside can be useful in this environment if an application repeatedly accesses the same data. However, a local cache is private and so different application instances could each have a copy of the same cached data. This data could quickly become inconsistent between caches, so it might be necessary to expire data held in a private cache and refresh it more frequently. In these scenarios, consider investigating the use of a shared or a distributed caching mechanism.

Use this pattern when:

- A cache doesn't provide native read-through and write-through operations.

- Resource demand is unpredictable. This pattern enables applications to load data on demand. It makes no assumptions about which data an application will require in advance.

This pattern might not be suitable:

- When the cached data set is static. If the data will fit into the available cache space, prime the cache with the data on startup and apply a policy that prevents the data from expiring.

- For caching session state information in a web application hosted in a web farm. In this environment, you should avoid introducing dependencies based on client-server affinity.

Have each component of the system participate in the decision-making process about the workflow of a business transaction, instead of relying on a central point of control.

In microservices architecture, it's often the case that a cloud-based application is divided into several small services that work together to process a business transaction end-to-end. To lower coupling between services, each service is responsible for a single business operation. Some benefits include faster development, smaller code base, and scalability. However, designing an efficient and scalable workflow is a challenge and often requires complex interservice communication.

The services communicate with each other by using well-defined APIs. Even a single business operation can result in multiple point-to-point calls amongst all services. A common pattern for communication is to use a centralized service that acts as the orchestrator. It acknowledges all incoming requests and delegates operations to the respective services. In doing so, it also manages the workflow of the entire business transaction. Each service just completes an operation and is not aware of the overall workflow.

The orchestrator pattern reduces point-to-point communication between services but has some drawbacks because of the tight coupling between the orchestrator and other services that participate in processing of the business transaction. To execute tasks in a sequence, the orchestrator needs to have some domain knowledge about the responsibilities of those services. If you want to add or remove services, existing logic will break, and you'll need to rewire portions of the communication path. While you can configure the workflow, add or remove services easily with a well-designed orchestrator, such an implementation is complex hard to maintain.

Let each service decide when and how a business operation is processed, instead of depending on a central orchestrator.

One way to implement choreography is to use the asynchronous messaging pattern to coordinate the business operations.

A client request publishes messages to a message queue. As messages arrive, they are pushed to subscribers, or services, interested in that message. Each subscribed service does their operation as indicated by the message and responds to the message queue with success or failure of the operation. In case of success, the service can push a message back to the same queue or a different message queue so that another service can continue the workflow if needed. If an operation fails, the message bus can retry that operation.

This way, the services choreograph the workflow among themselves without depending on an orchestrator or having direct communication between them.

Because there isn't point-to-point communication, this pattern helps reduce coupling between services. Also, it can remove the performance bottleneck caused by the orchestrator when it has to deal with all transactions.

Decentralizing the orchestrator can cause issues while managing the workflow.

If a service fails to complete a business operation, it can be difficult to recover from that failure. One way is to have the service indicate failure by firing an event. Another service subscribes to those failed events takes necessary actions such as applying compensating transactions to undo successful operations in a request. The failed service might also fail to fire an event for the failure. In that case, consider using a retry and, or time out mechanism to recognize that operation as a failure. For an example, see the Example section.

It's simple to implement a workflow when you want to process independent business operations in parallel. You can use a single message bus. However, the workflow can become complicated when choreography needs to occur in a sequence. For instance, Service C can start its operation only after Service A and Service B have completed their operations with success. One approach is to have multiple message buses that get messages in the required order. For more information, see the Example section.

The choreography pattern becomes a challenge if the number of services grow rapidly. Given the high number of independent moving parts, the workflow between services tends to get complex. Also, distributed tracing becomes difficult.

The orchestrator centrally manages the resiliency of the workflow and it can become a single point of failure. On the other hand, for choreography, the role is distributed between all services and resiliency becomes less robust.

Each service isn't only responsible for the resiliency of its operation but also the workflow. This responsibility can be burdensome for the service and hard to implement. Each service must retry transient, non-transient, and time-out failures, so that the request terminates gracefully, if needed. Also, the service must be diligent about communicating the success or failure of the operation so that other services can act accordingly.

Use the choreography pattern if you expect to update, remove, or add new services frequently. The entire app can be modified with lesser effort and minimal disruption to existing services.

Consider this pattern if you experience performance bottlenecks in the central orchestrator.

This pattern is a natural model for the serverless architecture where all services can be short lived, or event driven. Services can spin up because of an event, do their task, and are removed when the task is finished.

Handle faults that might take a variable amount of time to recover from, when connecting to a remote service or resource. This can improve the stability and resiliency of an application.

In a distributed environment, calls to remote resources and services can fail due to transient faults, such as slow network connections, timeouts, or the resources being overcommitted or temporarily unavailable. These faults typically correct themselves after a short period of time, and a robust cloud application should be prepared to handle them by using a strategy such as the Retry pattern.

However, there can also be situations where faults are due to unanticipated events, and that might take much longer to fix. These faults can range in severity from a partial loss of connectivity to the complete failure of a service. In these situations it might be pointless for an application to continually retry an operation that is unlikely to succeed, and instead the application should quickly accept that the operation has failed and handle this failure accordingly.

Additionally, if a service is very busy, failure in one part of the system might lead to cascading failures. For example, an operation that invokes a service could be configured to implement a timeout, and reply with a failure message if the service fails to respond within this period. However, this strategy could cause many concurrent requests to the same operation to be blocked until the timeout period expires. These blocked requests might hold critical system resources such as memory, threads, database connections, and so on. Consequently, these resources could become exhausted, causing failure of other possibly unrelated parts of the system that need to use the same resources. In these situations, it would be preferable for the operation to fail immediately, and only attempt to invoke the service if it's likely to succeed. Note that setting a shorter timeout might help to resolve this problem, but the timeout shouldn't be so short that the operation fails most of the time, even if the request to the service would eventually succeed.

The Circuit Breaker pattern, popularized by Michael Nygard in his book, Release It!, can prevent an application from repeatedly trying to execute an operation that's likely to fail. Allowing it to continue without waiting for the fault to be fixed or wasting CPU cycles while it determines that the fault is long lasting. The Circuit Breaker pattern also enables an application to detect whether the fault has been resolved. If the problem appears to have been fixed, the application can try to invoke the operation.

The purpose of the Circuit Breaker pattern is different than the Retry pattern. The Retry pattern enables an application to retry an operation in the expectation that it'll succeed. The Circuit Breaker pattern prevents an application from performing an operation that is likely to fail. An application can combine these two patterns by using the Retry pattern to invoke an operation through a circuit breaker. However, the retry logic should be sensitive to any exceptions returned by the circuit breaker and abandon retry attempts if the circuit breaker indicates that a fault is not transient.

A circuit breaker acts as a proxy for operations that might fail. The proxy should monitor the number of recent failures that have occurred, and use this information to decide whether to allow the operation to proceed, or simply return an exception immediately.

The proxy can be implemented as a state machine with the following states that mimic the functionality of an electrical circuit breaker:

-

Closed: The request from the application is routed to the operation. The proxy maintains a count of the number of recent failures, and if the call to the operation is unsuccessful the proxy increments this count. If the number of recent failures exceeds a specified threshold within a given time period, the proxy is placed into the Open state. At this point the proxy starts a timeout timer, and when this timer expires the proxy is placed into the Half-Open state.

The purpose of the timeout timer is to give the system time to fix the problem that caused the failure before allowing the application to try to perform the operation again.

-

Open: The request from the application fails immediately and an exception is returned to the application.

-

Half-Open: A limited number of requests from the application are allowed to pass through and invoke the operation. If these requests are successful, it's assumed that the fault that was previously causing the failure has been fixed and the circuit breaker switches to the Closed state (the failure counter is reset). If any request fails, the circuit breaker assumes that the fault is still present so it reverts back to the Open state and restarts the timeout timer to give the system a further period of time to recover from the failure.

The Half-Openstate is useful to prevent a recovering service from suddenly being flooded with requests. As a service recovers, it might be able to support a limited volume of requests until the recovery is complete, but while recovery is in progress a flood of work can cause the service to time out or fail again.

In the figure, the failure counter used by the Closed state is time based. It's automatically reset at periodic intervals. This helps to prevent the circuit breaker from entering the Open state if it experiences occasional failures. The failure threshold that trips the circuit breaker into the Open state is only reached when a specified number of failures have occurred during a specified interval. The counter used by the Half-Open state records the number of successful attempts to invoke the operation. The circuit breaker reverts to the Closed state after a specified number of consecutive operation invocations have been successful. If any invocation fails, the circuit breaker enters the Open state immediately and the success counter will be reset the next time it enters the Half-Open state.

How the system recovers is handled externally, possibly by restoring > or restarting a failed component or repairing a network connection.

The Circuit Breaker pattern provides stability while the system recovers from a failure and minimizes the impact on performance. It can help to maintain the response time of the system by quickly rejecting a request for an operation that's likely to fail, rather than waiting for the operation to time out, or never return. If the circuit breaker raises an event each time it changes state, this information can be used to monitor the health of the part of the system protected by the circuit breaker, or to alert an administrator when a circuit breaker trips to the Open state.

The pattern is customizable and can be adapted according to the type of the possible failure. For example, you can apply an increasing timeout timer to a circuit breaker. You could place the circuit breaker in the Open state for a few seconds initially, and then if the failure hasn't been resolved increase the timeout to a few minutes, and so on. In some cases, rather than the Open state returning failure and raising an exception, it could be useful to return a default value that is meaningful to the application.

You should consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

Exception Handling. An application invoking an operation through a circuit breaker must be prepared to handle the exceptions raised if the operation is unavailable. The way exceptions are handled will be application specific. For example, an application could temporarily degrade its functionality, invoke an alternative operation to try to perform the same task or obtain the same data, or report the exception to the user and ask them to try again later.

Types of Exceptions. A request might fail for many reasons, some of which might indicate a more severe type of failure than others. For example, a request might fail because a remote service has crashed and will take several minutes to recover, or because of a timeout due to the service being temporarily overloaded. A circuit breaker might be able to examine the types of exceptions that occur and adjust its strategy depending on the nature of these exceptions. For example, it might require a larger number of timeout exceptions to trip the circuit breaker to the Open state compared to the number of failures due to the service being completely unavailable.

Logging. A circuit breaker should log all failed requests (and possibly successful requests) to enable an administrator to monitor the health of the operation.

Recoverability. You should configure the circuit breaker to match the likely recovery pattern of the operation it's protecting. For example, if the circuit breaker remains in the Open state for a long period, it could raise exceptions even if the reason for the failure has been resolved. Similarly, a circuit breaker could fluctuate and reduce the response times of applications if it switches from the Open state to the Half-Open state too quickly.

Testing Failed Operations. In the Open state, rather than using a timer to determine when to switch to the Half-Open state, a circuit breaker can instead periodically ping the remote service or resource to determine whether it's become available again. This ping could take the form of an attempt to invoke an operation that had previously failed, or it could use a special operation provided by the remote service specifically for testing the health of the service, as described by the Health Endpoint Monitoring pattern.

Manual Override. In a system where the recovery time for a failing operation is extremely variable, it's beneficial to provide a manual reset option that enables an administrator to close a circuit breaker (and reset the failure counter). Similarly, an administrator could force a circuit breaker into the Open state (and restart the timeout timer) if the operation protected by the circuit breaker is temporarily unavailable.

Concurrency. The same circuit breaker could be accessed by a large number of concurrent instances of an application. The implementation shouldn't block concurrent requests or add excessive overhead to each call to an operation.

Resource Differentiation. Be careful when using a single circuit breaker for one type of resource if there might be multiple underlying independent providers. For example, in a data store that contains multiple shards, one shard might be fully accessible while another is experiencing a temporary issue. If the error responses in these scenarios are merged, an application might try to access some shards even when failure is highly likely, while access to other shards might be blocked even though it's likely to succeed.

Accelerated Circuit Breaking. Sometimes a failure response can contain enough information for the circuit breaker to trip immediately and stay tripped for a minimum amount of time. For example, the error response from a shared resource that's overloaded could indicate that an immediate retry isn't recommended and that the application should instead try again in a few minutes.

A service can return HTTP 429 (Too Many Requests) if it is throttling the client, or HTTP 503 (Service Unavailable) if the service is not currently available. The response can include additional information, such as the anticipated duration of the delay.

Replaying Failed Requests. In the Open state, rather than simply failing quickly, a circuit breaker could also record the details of each request to a journal and arrange for these requests to be replayed when the remote resource or service becomes available.

Inappropriate Timeouts on External Services. A circuit breaker might not be able to fully protect applications from operations that fail in external services that are configured with a lengthy timeout period. If the timeout is too long, a thread running a circuit breaker might be blocked for an extended period before the circuit breaker indicates that the operation has failed. In this time, many other application instances might also try to invoke the service through the circuit breaker and tie up a significant number of threads before they all fail.

Use this pattern:

- To prevent an application from trying to invoke a remote service or access a shared resource if this operation is highly likely to fail.

This pattern isn't recommended:

- For handling access to local private resources in an application, such as in-memory data structure. In this environment, using a circuit breaker would add overhead to your system.

- As a substitute for handling exceptions in the business logic of your applications.

Split a large message into a claim check and a payload. Send the claim check to the messaging platform and store the payload to an external service. This pattern allows large messages to be processed, while protecting the message bus and the client from being overwhelmed or slowed down. This pattern also helps to reduce costs, as storage is usually cheaper than resource units used by the messaging platform.

This pattern is also known as Reference-Based Messaging, and was originally described in the book Enterprise Integration Patterns, by Gregor Hohpe and Bobby Woolf.

A messaging-based architecture at some point must be able to send, receive, and manipulate large messages. Such messages may contain anything, including images (for example, MRI scans), sound files (for example, call-center calls), text documents, or any kind of binary data of arbitrary size.

Sending such large messages to the message bus directly is not recommended, because they require more resources and bandwidth to be consumed. Large messages can also slow down the entire solution, because messaging platforms are usually fine-tuned to handle huge quantities of small messages. Also, most messaging platforms have limits on message size, so you may need to work around these limits for large messages.

Store the entire message payload into an external service, such as a database. Get the reference to the stored payload, and send just that reference to the message bus. The reference acts like a claim check used to retrieve a piece of luggage, hence the name of the pattern. Clients interested in processing that specific message can use the obtained reference to retrieve the payload, if needed.

Consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

- Consider deleting the message data after consuming it, if you don't need to archive the messages. Although blob storage is relatively cheap, it costs some money in the long run, especially if there is a lot of data. Deleting the message can be done synchronously by the application that receives and processes the message, or asynchronously by a separate dedicated process. The asynchronous approach removes old data with no impact on the throughput and message processing performance of the receiving application.

- Storing and retrieving the message causes some additional overhead and latency. You may want to implement logic in the sending application to use this pattern only when the message size exceeds the data limit of the message bus. The pattern would be skipped for smaller messages. This approach would result in a conditional claim-check pattern.

This pattern should be used whenever a message cannot fit the supported message limit of the chosen message bus technology. For example, Event Hubs currently has a limit of 256 KB (Basic Tier), while Event Grid supports only 64-KB messages.

The pattern can also be used if the payload should be accessed only by services that are authorized to see it. By offloading the payload to an external resource, stricter authentication and authorization rules can be put in place, to ensure that security is enforced when sensitive data is stored in the payload.

The Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern separates read and update operations for a data store. Implementing CQRS in your application can maximize its performance, scalability, and security. The flexibility created by migrating to CQRS allows a system to better evolve over time and prevents update commands from causing merge conflicts at the domain level.

In traditional architectures, the same data model is used to query and update a database. That's simple and works well for basic CRUD operations. In more complex applications, however, this approach can become unwieldy. For example, on the read side, the application may perform many different queries, returning data transfer objects (DTOs) with different shapes. Object mapping can become complicated. On the write side, the model may implement complex validation and business logic. As a result, you can end up with an overly complex model that does too much.

Read and write workloads are often asymmetrical, with very different performance and scale requirements.

- There is often a mismatch between the read and write representations of the data, such as additional columns or properties that must be updated correctly even though they aren't required as part of an operation.

- Data contention can occur when operations are performed in parallel on the same set of data.

- The traditional approach can have a negative effect on performance due to load on the data store and data access layer, and the complexity of queries required to retrieve information.

- Managing security and permissions can become complex, because each entity is subject to both read and write operations, which might expose data in the wrong context.

CQRS separates reads and writes into different models, using commands to update data, and queries to read data.

- Commands should be task based, rather than data centric. ("Book hotel room", not "set ReservationStatus to Reserved").

- Commands may be placed on a queue for asynchronous processing, rather than being processed synchronously.

- Queries never modify the database. A query returns a DTO that does not encapsulate any domain knowledge.

The models can then be isolated, as shown in the following diagram, although that's not an absolute requirement.

Having separate query and update models simplifies the design and implementation. However, one disadvantage is that CQRS code can't automatically be generated from a database schema using scaffolding mechanisms such as O/RM tools.

For greater isolation, you can physically separate the read data from the write data. In that case, the read database can use its own data schema that is optimized for queries. For example, it can store a materialized view of the data, in order to avoid complex joins or complex O/RM mappings. It might even use a different type of data store. For example, the write database might be relational, while the read database is a document database.

If separate read and write databases are used, they must be kept in sync. Typically this is accomplished by having the write model publish an event whenever it updates the database. Updating the database and publishing the event must occur in a single transaction.

The read store can be a read-only replica of the write store, or the read and write stores can have a different structure altogether. Using multiple read-only replicas can increase query performance, especially in distributed scenarios where read-only replicas are located close to the application instances.

Separation of the read and write stores also allows each to be scaled appropriately to match the load. For example, read stores typically encounter a much higher load than write stores.

Some implementations of CQRS use the Event Sourcing pattern. With this pattern, application state is stored as a sequence of events. Each event represents a set of changes to the data. The current state is constructed by replaying the events. In a CQRS context, one benefit of Event Sourcing is that the same events can be used to notify other components --- in particular, to notify the read model. The read model uses the events to create a snapshot of the current state, which is more efficient for queries. However, Event Sourcing adds complexity to the design.

Benefits of CQRS include:

- Independent scaling. CQRS allows the read and write workloads to scale independently, and may result in fewer lock contentions.

- Optimized data schemas. The read side can use a schema that is optimized for queries, while the write side uses a schema that is optimized for updates.

- Security. It's easier to ensure that only the right domain entities are performing writes on the data.

- Separation of concerns. Segregating the read and write sides can result in models that are more maintainable and flexible. Most of the complex business logic goes into the write model. The read model can be relatively simple.

- Simpler queries. By storing a materialized view in the read database, the application can avoid complex joins when querying.

Some challenges of implementing this pattern include:

- Complexity. The basic idea of CQRS is simple. But it can lead to a more complex application design, especially if they include the Event Sourcing pattern.

- Messaging. Although CQRS does not require messaging, it's common to use messaging to process commands and publish update events. In that case, the application must handle message failures or duplicate messages.

- Eventual consistency. If you separate the read and write databases, the read data may be stale. The read model store must be updated to reflect changes to the write model store, and it can be difficult to detect when a user has issued a request based on stale read data.

Consider CQRS for the following scenarios:

- Collaborative domains where many users access the same data in parallel. CQRS allows you to define commands with enough granularity to minimize merge conflicts at the domain level, and conflicts that do arise can be merged by the command.

- Task-based user interfaces where users are guided through a complex process as a series of steps or with complex domain models. The write model has a full command-processing stack with business logic, input validation, and business validation. The write model may treat a set of associated objects as a single unit for data changes (an aggregate, in DDD terminology) and ensure that these objects are always in a consistent state. The read model has no business logic or validation stack, and just returns a DTO for use in a view model. The read model is eventually consistent with the write model.

- Scenarios where performance of data reads must be fine tuned separately from performance of data writes, especially when the number of reads is much greater than the number of writes. In this scenario, you can scale out the read model, but run the write model on just a few instances. A small number of write model instances also helps to minimize the occurrence of merge conflicts.

- Scenarios where one team of developers can focus on the complex domain model that is part of the write model, and another team can focus on the read model and the user interfaces.

- Scenarios where the system is expected to evolve over time and might contain multiple versions of the model, or where business rules change regularly.

- Integration with other systems, especially in combination with event sourcing, where the temporal failure of one subsystem shouldn't affect the availability of the others.

This pattern isn't recommended when:

- The domain or the business rules are simple.

- A simple CRUD-style user interface and data access operations are sufficient.

Consider applying CQRS to limited sections of your system where it will be most valuable.

Undo the work performed by a series of steps, which together define an eventually consistent operation, if one or more of the steps fail. Operations that follow the eventual consistency model are commonly found in cloud-hosted applications that implement complex business processes and workflows.

Applications running in the cloud frequently modify data. This data might be spread across various data sources held in different geographic locations. To avoid contention and improve performance in a distributed environment, an application shouldn't try to provide strong transactional consistency. Rather, the application should implement eventual consistency. In this model, a typical business operation consists of a series of separate steps. While these steps are being performed, the overall view of the system state might be inconsistent, but when the operation has completed and all of the steps have been executed the system should become consistent again.

The Data Consistency Primer provides information about why distributed transactions don't scale well, and the principles of the eventual consistency model.

A challenge in the eventual consistency model is how to handle a step that has failed. In this case it might be necessary to undo all of the work completed by the previous steps in the operation. However, the data can't simply be rolled back because other concurrent instances of the application might have changed it. Even in cases where the data hasn't been changed by a concurrent instance, undoing a step might not simply be a matter of restoring the original state. It might be necessary to apply various business-specific rules (see the travel website described in the Example section).

If an operation that implements eventual consistency spans several heterogeneous data stores, undoing the steps in the operation will require visiting each data store in turn. The work performed in every data store must be undone reliably to prevent the system from remaining inconsistent.

Not all data affected by an operation that implements eventual consistency might be held in a database. In a service oriented architecture (SOA) environment an operation could invoke an action in a service, and cause a change in the state held by that service. To undo the operation, this state change must also be undone. This can involve invoking the service again and performing another action that reverses the effects of the first.

The solution is to implement a compensating transaction. The steps in a compensating transaction must undo the effects of the steps in the original operation. A compensating transaction might not be able to simply replace the current state with the state the system was in at the start of the operation because this approach could overwrite changes made by other concurrent instances of an application. Instead, it must be an intelligent process that takes into account any work done by concurrent instances. This process will usually be application specific, driven by the nature of the work performed by the original operation.

A common approach is to use a workflow to implement an eventually consistent operation that requires compensation. As the original operation proceeds, the system records information about each step and how the work performed by that step can be undone. If the operation fails at any point, the workflow rewinds back through the steps it's completed and performs the work that reverses each step. Note that a compensating transaction might not have to undo the work in the exact reverse order of the original operation, and it might be possible to perform some of the undo steps in parallel.

This approach is similar to the Sagas strategy discussed in Clemens Vasters' blog.

A compensating transaction is also an eventually consistent operation and it could also fail. The system should be able to resume the compensating transaction at the point of failure and continue. It might be necessary to repeat a step that's failed, so the steps in a compensating transaction should be defined as idempotent commands. For more information, see Idempotency Patterns on Jonathan Oliver's blog.

In some cases it might not be possible to recover from a step that has failed except through manual intervention. In these situations the system should raise an alert and provide as much information as possible about the reason for the failure.

Consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

It might not be easy to determine when a step in an operation that implements eventual consistency has failed. A step might not fail immediately, but instead could block. It might be necessary to implement some form of time-out mechanism.

-Compensation logic isn't easily generalized. A compensating transaction is application specific. It relies on the application having sufficient information to be able to undo the effects of each step in a failed operation.

You should define the steps in a compensating transaction as idempotent commands. This enables the steps to be repeated if the compensating transaction itself fails.

The infrastructure that handles the steps in the original operation, and the compensating transaction, must be resilient. It must not lose the information required to compensate for a failing step, and it must be able to reliably monitor the progress of the compensation logic.

A compensating transaction doesn't necessarily return the data in the system to the state it was in at the start of the original operation. Instead, it compensates for the work performed by the steps that completed successfully before the operation failed.

The order of the steps in the compensating transaction doesn't necessarily have to be the exact opposite of the steps in the original operation. For example, one data store might be more sensitive to inconsistencies than another, and so the steps in the compensating transaction that undo the changes to this store should occur first.

Placing a short-term timeout-based lock on each resource that's required to complete an operation, and obtaining these resources in advance, can help increase the likelihood that the overall activity will succeed. The work should be performed only after all the resources have been acquired. All actions must be finalized before the locks expire.

Consider using retry logic that is more forgiving than usual to minimize failures that trigger a compensating transaction. If a step in an operation that implements eventual consistency fails, try handling the failure as a transient exception and repeat the step. Only stop the operation and initiate a compensating transaction if a step fails repeatedly or irrecoverably.

Many of the challenges of implementing a compensating transaction are the same as those with implementing eventual consistency. See the section Considerations for Implementing Eventual Consistency in the Data Consistency Primer for more information.

Use this pattern only for operations that must be undone if they fail. If possible, design solutions to avoid the complexity of requiring compensating transactions.

Enable multiple concurrent consumers to process messages received on the same messaging channel. This enables a system to process multiple messages concurrently to optimize throughput, to improve scalability and availability, and to balance the workload.

An application running in the cloud is expected to handle a large number of requests. Rather than process each request synchronously, a common technique is for the application to pass them through a messaging system to another service (a consumer service) that handles them asynchronously. This strategy helps to ensure that the business logic in the application isn't blocked while the requests are being processed.

The number of requests can vary significantly over time for many reasons. A sudden increase in user activity or aggregated requests coming from multiple tenants can cause an unpredictable workload. At peak hours a system might need to process many hundreds of requests per second, while at other times the number could be very small. Additionally, the nature of the work performed to handle these requests might be highly variable. Using a single instance of the consumer service can cause that instance to become flooded with requests, or the messaging system might be overloaded by an influx of messages coming from the application. To handle this fluctuating workload, the system can run multiple instances of the consumer service. However, these consumers must be coordinated to ensure that each message is only delivered to a single consumer. The workload also needs to be load balanced across consumers to prevent an instance from becoming a bottleneck.

Use a message queue to implement the communication channel between the application and the instances of the consumer service. The application posts requests in the form of messages to the queue, and the consumer service instances receive messages from the queue and process them. This approach enables the same pool of consumer service instances to handle messages from any instance of the application. The figure illustrates using a message queue to distribute work to instances of a service.

This solution has the following benefits: